Mosque Name: Palmyra Central Mosque

Country: Syria

City: Palmyra

Year of construction (AH): 18

Year of construction (AD): 640

GPS: 34°33′4.00″N,38°16′5.10″E

ArchNet: https://www.archnet.org/sites/14868

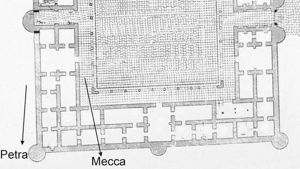

Gibson Classification: Petra

Rebuilt facing Mecca:

For a Link to the Qibla Tool Click Here

Description:

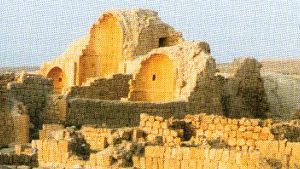

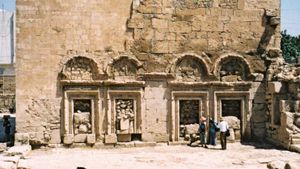

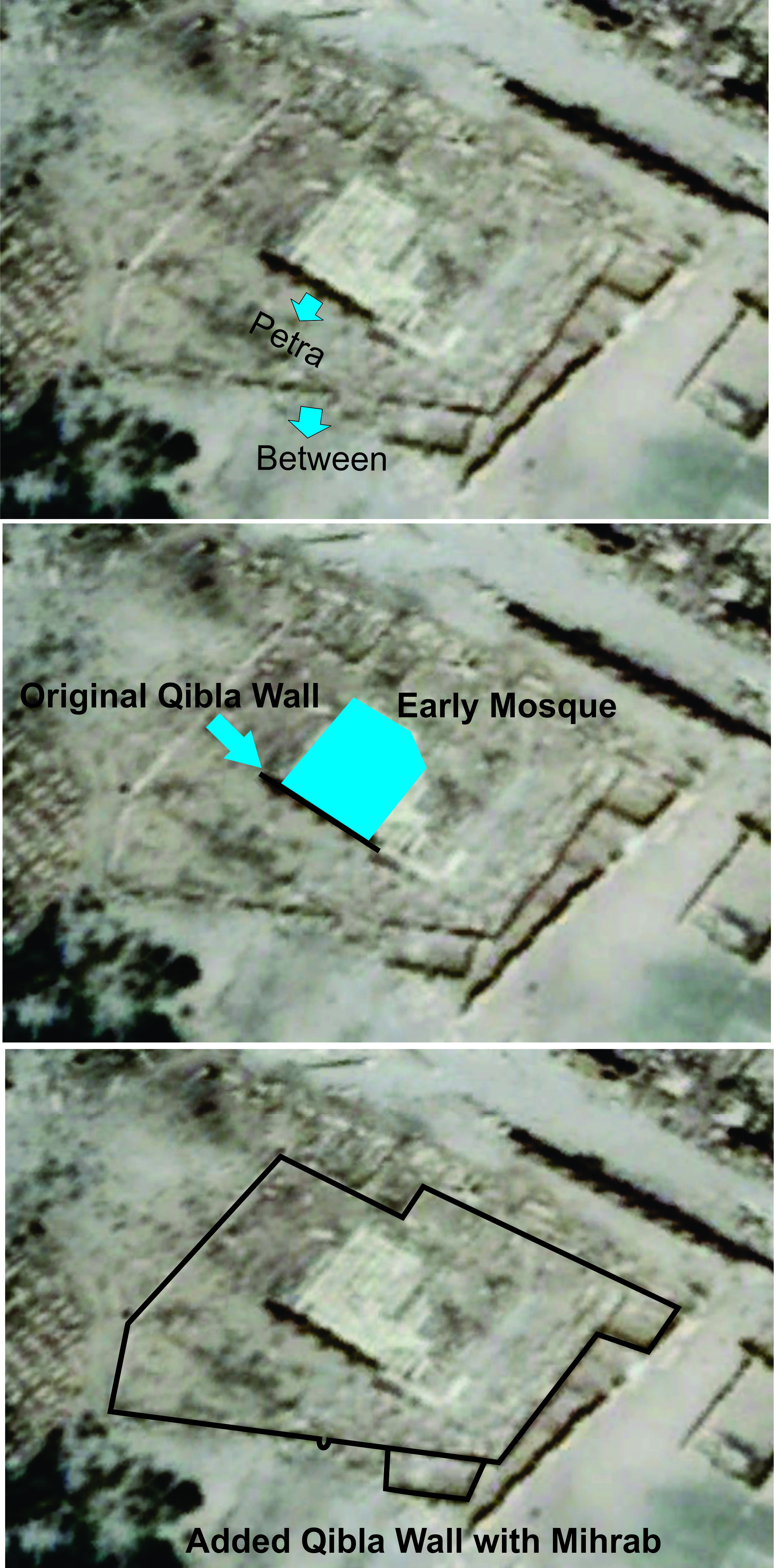

The large central mosque in Palmyra was built early in the Islamic era. A Roman structure originally occupied the location, which stands near a major cross roads of the old city. It seems early Muslims recognized the building’s orientation as facing Petra, so they re-purposed the building to be a mosque with one wall used as a Petra Qibla wall.

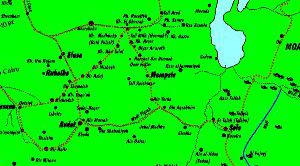

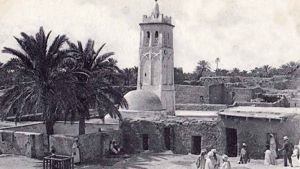

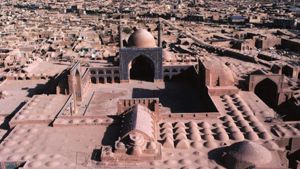

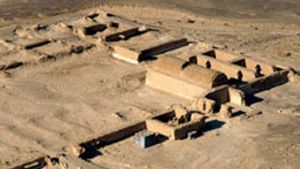

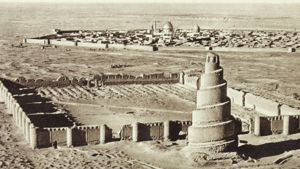

An aerial view of Palmyra.

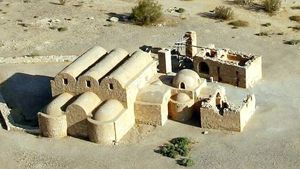

Later, a new Qibla wall was constructed on the same site, but south of the earlier structure. This wall created a much larger worship area. The new Qibla wall had a mihrab and faced the Between position. See below.

The original building was not destroyed, so it was possible for the faithful to pray in either direction.

There are several issues with the archeology done in Palmyra. Archaeological excavations began in Palmyra back in the 1920s, and some early excavations seemed to be little more that treasure seeking digs, some of which were never recorded. Additionally, some reports were poorly written, some never published, and others with only rudimentary drawings. However, since the 1950s, several modern digs have taken place. However, it is unfortunate that some of the earlier digs disrupted important sites.

The larger mosque and the re-purposed Roman building were excavated in 1962 by a team from the Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums of Syria led by Adnan Bounni. The excavation was apparently done without any recording of the stratigraphy. Antoni Ostraz, when planning the eastern part of the Colonnaded Street, produced an architectural plan, but it includes only the Roman remains and not the later wider mosque. It is possible now to do more work on the standing remains, but it is difficult to know how much of the Roman and Islamic structures were removed during the earlier excavations.

Despite this, it is possible to still view the two mosques. The earliest mosque, (the repurposed Roman structure) faces Petra but does not have a Mihrab, as it was used prior to the development of the Mihrab in 89 AH or 708 AD. The later mosque has a mihrab with a Qibla facing the Between Position.

Below are photos taken from a paper by Denis Genequand. We extend special thanks for his report and photos taken from the paper:An Early Islamic Mosque in Palmyra, by Denis Genequand (Levant 2008 VOL 40 NO 1)

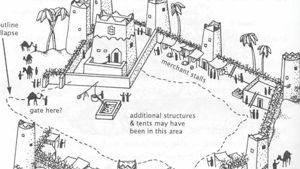

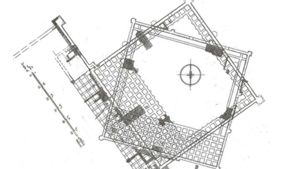

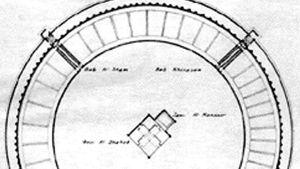

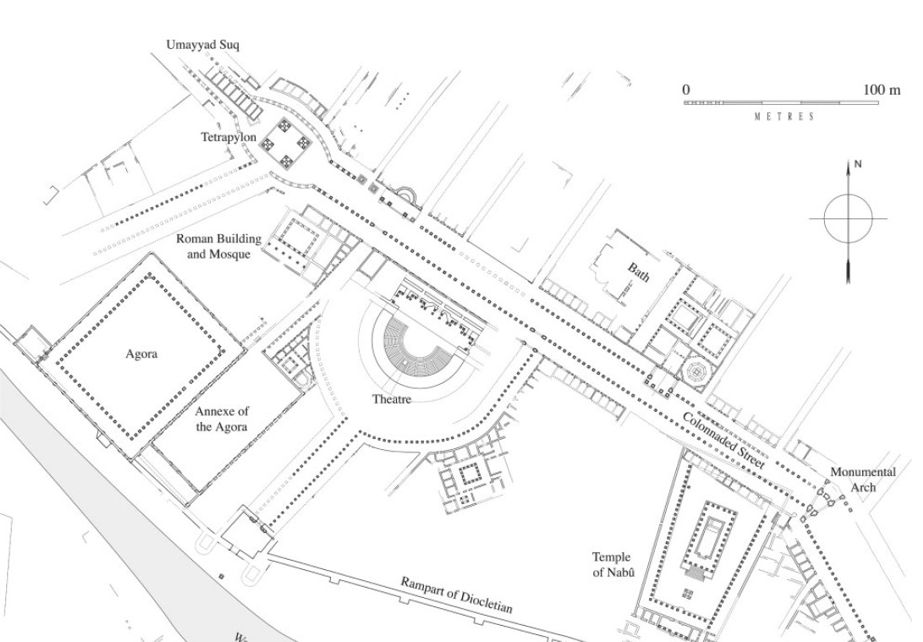

Plan of the central sector of Palmyra, including the Agora, the Theatre, the Tetrapylon, part of the Colonnaded Street and the Roman building/mosque. The Umayyad suq was extending to the west of the Tetrapylon (drawing, Thibaud Fournet)

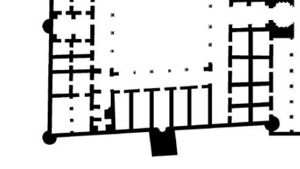

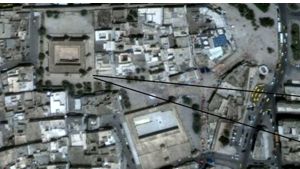

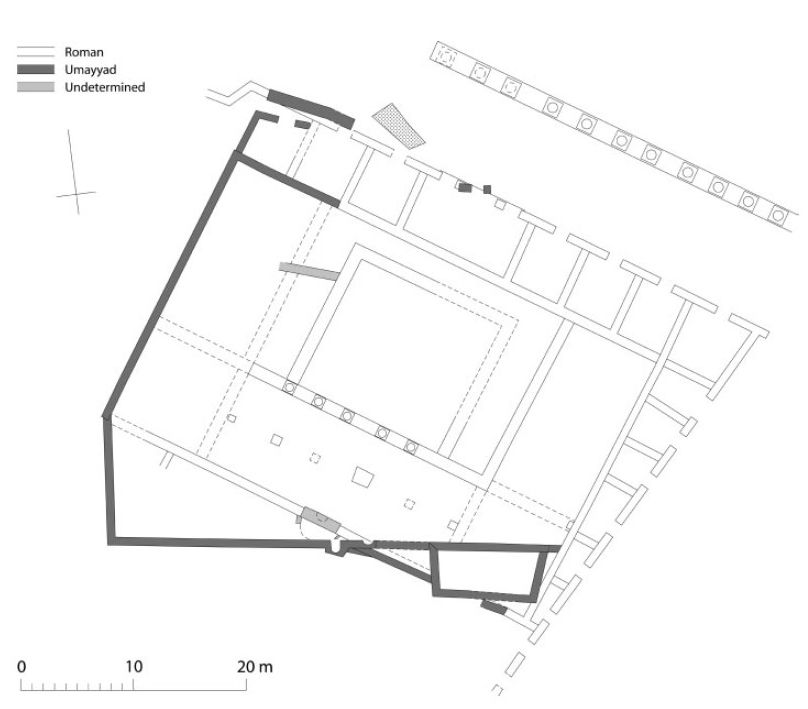

Notice the Mihrabs on the later mosque. (survey by Marie-Ce´cile Bosert and Denis Genequand; drawing, Marie-Ce´ cile Bosert and Marion Berti)

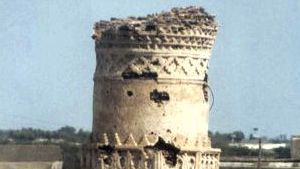

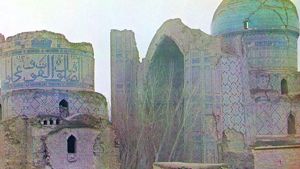

Central part of the qibla wall with the mihrab and a lateral niche (photo, Denis Genequand)

The mihrab (photo, Denis Genequand)

Early and Roman Palmyra

To learn more about the history of the city of Palmyra CLICK HERE

Islamic Palmyra

Palmyra was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate after its 634 capture by the Muslim general Khalid ibn al-Walid, who took the city on his way to Damascus; an 18-day march by his army through the Syrian Desert from Mesopotamia

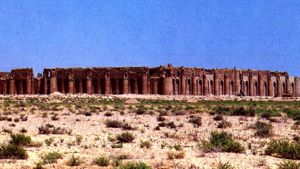

During the 2006 archeological season a large mosque was re-discovered in Palmyra which is likely to be the Umayyad congregational mosque.

Since before the coming of Islam, Palmyra/Tadmur and its region were part of the domain of Kalb, a Yamani tribe. Palmyra and its region were conquered in the mid-630s, perhaps even as early as H 13/AD 634 by the general Khalid b. al-Walid (al-Baladhuri, Futuh al-Buldan, 111). After this, Palmyra stayed in the hands of Kalb and was incorporated in the jund of Homs. According to Abu Mikhnaf, cited by al-Tabari (Ta’rikh, II, 482), in H 64/AD 683–684 most of the Banu Umayya were driven out of Medina, Meccaand the Hijaz by ‘Abdallah b. al-Zubayr and went to Palmyra. It was there that Marwan b. al-Hakam received the oath of allegiance by the Banu Umayya and by the people of Palmyra, before moving with an army against al-Dahhak b. Qays at the battle of Marj Rahit and then becoming caliph in H 65/AD 684. This was an important political event, which marked a shift of power from the Sufyanid to the Marwanid branch of the Umayyad family.

In H 126/AD 744 the city was apparently still well fortified, as during the rebellion of Yazid b. al-Walid someone proposed to al-Walid b. Yazid to take refuge there (al-Tabari, Ta’rikh, II, 1796). The latter finally decided to go to al-Bakhra’, 21 km south of Palmyra, where he was killed by the soldiers of ‘Abd al-‘Aziz b. al-Hajjaj b. ‘Abd al-Malik and buried there (al-Tabari, Ta’rikh, II, 1795–1807; Genequand 2004b). The city, and particularly its ramparts, subsequently suffered an amount of damage difficult to estimate after having supported Sulayman b. Hisham against the caliph Marwan b. Muhammad in H 127/AD 744–745 (al-Tabari, Ta’rikh, II, 1892, 1896, 1912; Ibn al-Faqih, Kitab al-Buldan, 110; Yaqut, Mu‘jam al-Buldan, II, 17) and again in H 132/AD 750 during the fights related to the fall of the Umayyad dynasty (al-Tabari, Ta’rikh, III, 53–54; al-Isfahani, Aghani, XVIII, 150).

A bishopric was maintained in Palmyra during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods and bishops were still ordained in, or shortly after, H 177/AD 793 (bishop Symeon, formerly in the monastery of Mar Jacob in Cyrrhus) and H 202/AD 818 (bishop Iohannan/John III, formerly at the monastery of Mar Hanania) (Michael the Syrian, vol. III, 451, 453).

By the end of the 10th century AD, the geographer al-Muqaddasi described Palmyra as a qasaba, a word implying a rather small town or settlement encompassed with some sort of enclosure (Ahsan al- Taqasim, 156).

This above section on Islamic Palmyra was taken from the paper: An Early Islamic Mosque in Palmyra, by Denis Genequand (Levant 2008 VOL 40 NO 1)

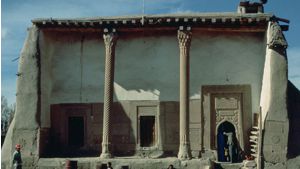

The Between Mosque was built with a corrected orientation. But it still does not face Mecca. Rather it faces the Between position begun by General Hajjaj. The overall dimensions of this smaller mosque (41 x 42.50 m, considering the width of the qibla wall and the longest side) correspond roughly to the dimensions of the Jarash mosque (38.90 6 44.50 m) or of the Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi mosque (38 6 48.50 m). That makes the structure one of the smallest of the Umayyad congregational mosques built in Bilad al- sham. But the dimensions and proportions of the Palmyra mosque fits well with a trend that prevailed during the reign of Hisham b. ‘Abd al-Malik (H 105– 125/AD 724–743), as recently demonstrated by Walmsley and Damgaard (2005, 375).

References:

Genequand, Denis, 2008. “An Early Islamic Mosque in Palmyra”, Levant 40(1): 3-15. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/175638008x284143

Genequand, Denis, and al-Asʿad, Walid, 2010. “Rapport préliminaires sur les travaux des missions archéologiques Syro-Suisses de Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi et de Palmyre en 2008”, Chronique Archéologique en Syrie 4: 315-320. https://dataspace.princeton.edu/handle/88435/dsp011r66j363w

Genequand, Denis, 2012. Les établissements des élites omeyyades en Palmyrène et au Proche-Orient, Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 200, Beirut: IFPO, 52-66. https://www.ifporient.org/978-2-35159-380-6/