Mosque Name: Humeima Tombs

Country: Jordan

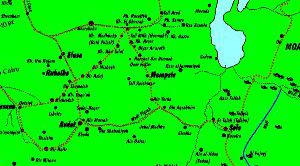

City: Humeima

Year of construction (AH): 93 AD

Year of construction (AD): 712

GPS: 29.949629 35.34612

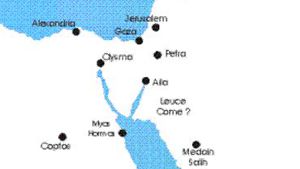

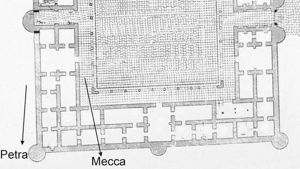

Gibson Classification: Between

Rebuilt facing Mecca: Never

For a Link to the Qibla Tool Click Here

Description:

When archeologists were excavating the Humeima site they were aware that the Qasr was the home of the famous Abbas family. However, when they excavated the manor house they did not find a mihrab niche anywhere in the house. Unaware of the Petra option, they began looking farther and farther afield for a mosque that they could identify. In essence they were looking for a mihrab niche in a building that was constructed before the mihrab nice was invented.

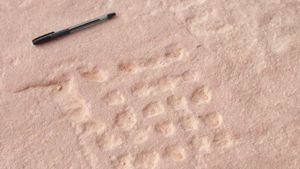

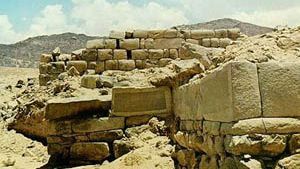

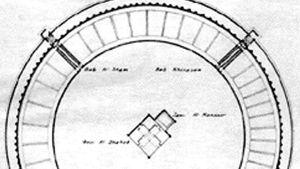

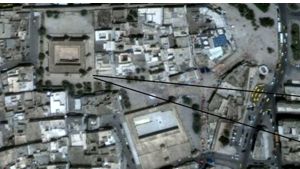

Their report tells us that had not carefully examined a series of small building to the east of the Qasr, because they considered the buildings to be of a later date. They felt that these buildings were the homes of the agricultural workers who worked the Abbas fields and orchards that were watered by the nearby wadi. After the Abbas family moved to Iraq to take part in politics, the agricultural workers continued on looking after the gardens and orchards. However, on the last day of one of their dig seasons, the archeologists examined the foundations of these small buildings and discovered that there were apparently two that could have been used as a mosque at some time. Today one of these has been somewhat restored, and we can see that that this small structure had a different Qibla than the Qasr building. But there are problems. The mihrab could only be understood by a few stones placed on the ground. The rest of the building was in ruins. If you look at a satellite photo you can see multiple walls indicating various small buildings that stood clustered together. One of these buildings has been restored by the archeologists, but there is some tension over the shape of the mihrab niche. Another of the small buildings also has its own niche.

I visited this Qasr several times over the years when the archeologists were excavating, and I noticed that the mihrab stones in the small structures had been placed differently at different times. I was mostly interested in the Nabataean ruins, but I observed their work. It seemed that the archeologists could not decide just how to place the mihrab stones to make them line up with Mecca. Of course, once some well-meaning Arab arranged the stones a little ‘better’ the original setting of those stones was lost. I have searched my photos for pictures of the various mihrab arrangements I saw, but unfortunately none have survived from those visits.

The small structures are an issue. Were there a cluster of tiny mosques on this site? What about the Qibla, they they face too far west to face Mecca. They even face too far west to be a true Between Qibla. One of the issues is that the buildings were tumbled down, and the excavation team only examined them on the lat day. It was a year later when they returned, and by then the mihrab stones were no longer in situ.

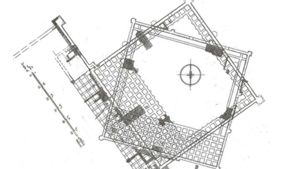

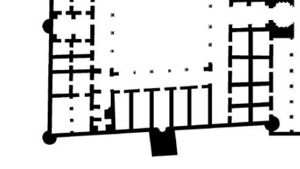

So from Early Islamic records we know that the construction of the Abbas Qasr took place around 67 AH immediately after the Abbas family purchased the site. From examining other Rashidun Qasrs, we can see the use of wide, shallow rooms for prayer. This can be identified in the main qasr building.

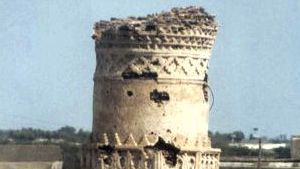

al-Ḥarawî tells us: “*Al-Ḥumayma is a village that contains the tomb of Muḥammad ibn ‘Alî ibn ‘Abd Allāh ibn al-‘Abbās, imâm al-Manṣūr’s father.*” (Meri 2004, 36; cf. Sourdel 1957, 44 in reference mentioned below). It is interesting that al-Harawi uses the Arabic word qabr “grave” here (which Meri and Sourdel translate as “tomb”). Qabr is the word that al-Harawi uses most frequently throughout the book, and only occasionally does he use some other words like maqâm or mashḥad, which would imply some monument that is a goal of pilgrimage. The small tombs clusterd together probably included other Abbas family members who wanted to be buried close to the illustrus imam of Mansur’s father.

The archaeological investigations of the site by Oleson and Reeves have not revealed any hint of a shrine from Islamic times, and quite possibly there never was any monumental shrine here. Other Arab geographers from the early Islamic period mention Humayma without necessarily implying that there was a shrine. No cemetery from the early Islamic period has been identified. The modern Bedouin cemetery is some distance to the south.

More information can be found on page 165 in: Islamic Heritage Sites in Jordan, A Student’s Gazetteer, prepared by the MA-Students of The German-Jordanian University, in Architectural Conservation School for Architecture and Built Environment Academic Years, 2017 - 2020, edited by Thomas M. Weber-Karyotakis & Ammar Khammash with Hussein al-Aza‘at, Nader Atiyeh, Catreena Hamarneh, Khairiyeh al-Kukhun & Robert Schick. GJU, Amman 2020

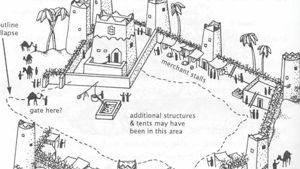

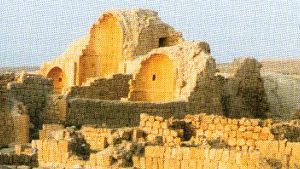

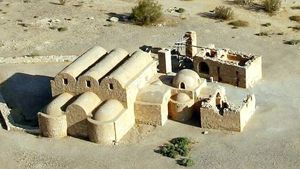

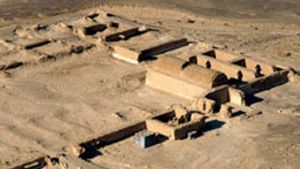

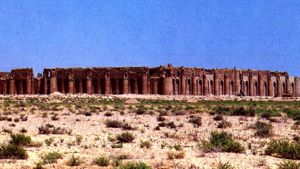

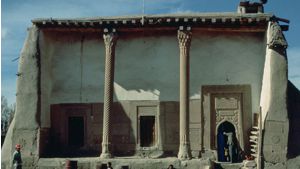

The Humeima Qasr stands in the forefront. The later small mosque was been rebuilt from the ruins, and stand behind the Qasr.

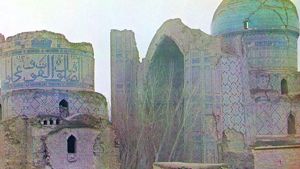

One of the reconstructed mihrab niches is in the foreground, and the partially reconstructed tomb stands behind it.

References:

Foote, Rebecca M., 2007. “From Residence to Revolutionary Headquarters: The Early Islamic Qasr and Mosque Complex at al-Humayma and Its 8th-Century Context”, in: Thomas E. Levy, P.M. Michèle Daviau, Randall W. Younker and May Shaer (eds.), Crossing Jordan: North American Contributions to the Archaeology of Jordan, London and Oakville: Equinox Publishing, 457-465.

Foote, Rebecca M., 1999. “Frescoes and Carved Ivory from the Abbasid Family Homestead at Humeima”, Journal of Roman Archaeology 12: 423-428. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-roman-archaeology/article/abs/frescoes-and-carved-ivory-from-the-abbasid-family-homestead-at-humeima/BEDF434F3D712D82968D8DECDDB86D82

Schick, Robert, 2007. “Al-Ḥumayma and the Abbasid Family”, Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan 9: 345-355. http://publication.doa.gov.jo/Publications/ViewChapterPublic/410

Oleson, John Peter, ʿAmr, Khairieh, Foote, Rebecca, Logan, Judy, Reeves, M. Barbara, and Robert Schick, 1999. “Preliminary report of the al-Humayma excavation project, 1995, 1996, 1998”, Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 43: 411-450. http://publication.doa.gov.jo/Publications/ViewChapterPublic/770

Oleson, John Peter, Baker, Gregory S., de Bruijn, Erik, Foote, Rebecca M., Logan, Judy, Reeves, M. Barbara, and Andrew N. Sherwood, 2003. “Preliminary Report of al-Humayma Excavation Project, 2000, 2002”, Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 47: 37-64. http://publication.doa.gov.jo/Publications/ViewChapterPublic/715

Oleson, John Peter, Reeves, M. Barbara, Baker, Gregory S., de Bruijn, Erik, Gerber, Y., Nikolic, M., and Andrew N. Sherwood, 2008. “Preliminary Report on Excavations at Humayma, Ancient Hawara, 2004 and 2005”, Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 52: 309-342. http://publication.doa.gov.jo/Publications/ViewChapterPublic/326