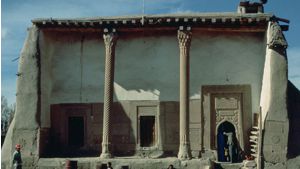

Mosque Name: Kalyan mosque

Country: Afghanistan

City: Herat

Year of construction (AH): 712 CE

Year of construction (AD): 92 AD

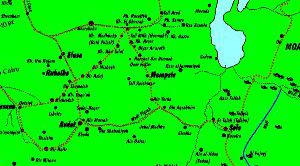

GPS: 39.775917 64.414086

Original Qibla: Unknown, faces just north of Jerusalem

Last Rebuilt: 16th century

For a Link to the Qibla Tool Click Here

Description:

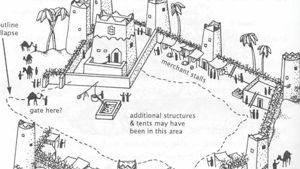

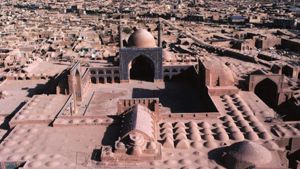

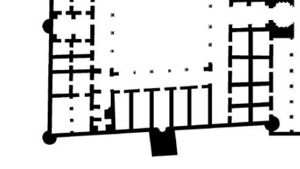

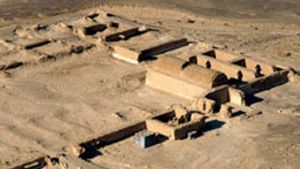

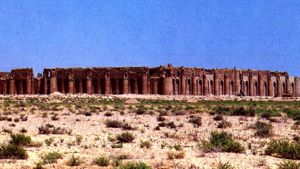

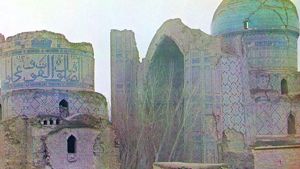

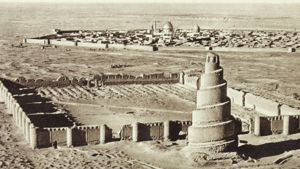

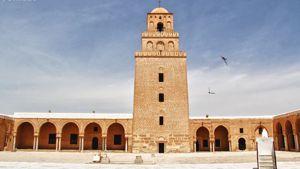

The Kalyan mosque stands face-to-face with the Mir-Arab Madrasa, forming the Po-i-Kalyan Ensemble with the great Kalyan minaret between them. It serves as the city’s Friday (congregational) mosque and is the largest in central Asia apart from the Bibi Khanum mosque in Samarkand and the Friday Mosque of Herat, Afghanistan. Completed by the 1530s, it is the earliest of the major Shaibanid monuments of Bukhara and a symbol of the city’s rising status in the 16th century.

Friday mosques have existed in Bukhara from the very beginning of the region’s turn to Islam. In the year 709, scarcely a century after Muhammad’s revelations, the city fell to the armies of Qutayba ibn Muslim (669-715⁄16), the Umayyad governor of Khorasan. The historian al-Narshakhi, writing in the 10th century, noted that Qutayba built a grand mosque inside the city’s citadel in 712⁄13 on the site of a former temple. To attract the newly-converted Qutayba resorted to paying two *dirhams*to each attendee and allowed the prayers to be held in the native Sogdian language rather than Arabic.

Al-Narshakhi provides excellent records of subsequent events. By the year 770, attendance had grown so much that the contemporary governor, Khalid Barmaki, built a new mosque between the citadel and the city. The old mosque gradually deteriorated and was eventually turned into the city’s tax bureau. The new mosque (or another replacement built after 793⁄94) was later enlarged by a third by Ismail Samani in the 10th century. Early in the reign of one of his successors, Nasr II (r. 914-943) the mosque collapsed on a Friday, killing a great number of people. Al-Narshakhi wrote that “In the entire city many people perished, so afterwards the city of Bukhara seemed empty” (Frye translation, p. 67). The mosque was quickly reconstructed over the course of the year, only to collapse again—this time without casualties. A replacement built five years later proved more durable, surviving until the year 1068 when it was destroyed by fire during a battle for control of the city.

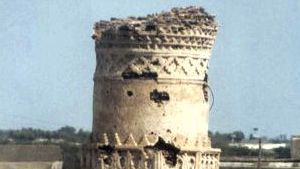

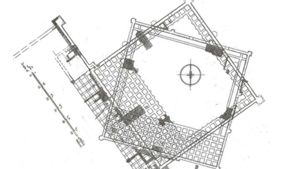

Al-Narshahki’s text was edited and appended by subsequent authors through the 11th-13th centuries, providing further details. Following the mosque’s destruction in 1068 it was quickly rebuilt. Several further iterations were built at various times over the next century, each progressively farther from the citadel, finally reaching the present site in 1121-22. More than likely the present mosque follows the same footprint as the 12th century structure which was constructed by Arslan Khan II (r. 1102-29), a Kara-Khanid ruler. That mosque survived only a few years until the minaret collapsed, destroying two-thirds of the mosque. A subsequent reconstruction stood until 1220 when the city was taken by Genghis Khan’s armies. The Khan himself visited the site and was so awe-struck by its size that he incorrectly believed it was the ruling family’s palace. He also marveled at the minaret that stood (and still stands) outside. While he ordered the minaret spared, his troops set fire to the mosque and left it a ruined hulk. For several subsequent centuries the ruins stood in the open air, a bitter reminder of the near death-blow the Khan had brought to the ancient city.

The ruins were finally cleared in the Timurud era, but it is not known how much of the mosque had been rebuilt before the Shaibanid dynasty took control of the city in the early 16th century. The energetic ruler Ubaydullah-khan, who was later to serve as the Shaibanid Khan (ruling in that capacity from 1534-39), spent his early years as governor of Bukhara; under his rule the facade of the mosque was completed in 1514 or 1515. Further ornament was added through the 1530s at the same time that the adjacent Mir-i Arab Madrasa was established. The original minaret was retained, providing a crucial link to the city’s pre-Mongol past.

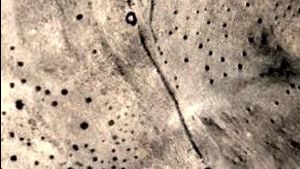

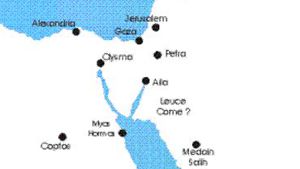

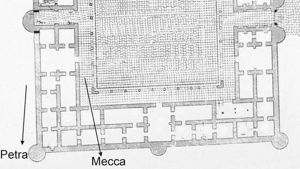

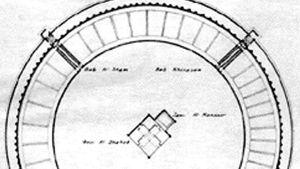

The Qibla of this mosque is indeed a puzzle. It faces 2.6 degrees north of Jerusalem and 5.8 degrees north of Petra, so it could be considered facing either of these places. It is over than 26 degrees from Mecca. Dan Gibson classified this mosque as Jerusalem but suspects it was intended to be a Petra facing mosque.

copyright 2019 Timothy M. Ciccone. Photographed February 2019

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!