Name: Kizimkazi Mosque

Country: Tanzania

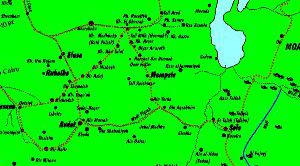

City: South of Zanzibar

GPS: -6.436123 39.462377

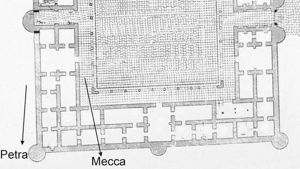

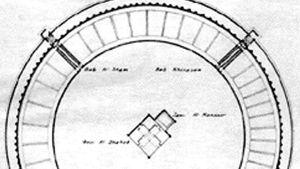

Orientation: 328 degrees

Petra / Between: 354 and Mecca 0.72

Description:

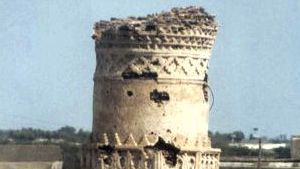

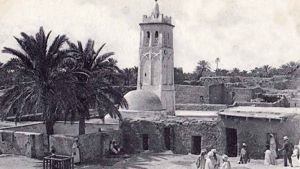

Among the relics and monuments on the East African coast that prove that Iranians once lived there, Kizimkazi Mosque is the second oldest mosque in Zanzibar, Tanzania, built by Shirazi people after the Great Mosque of Kilwa on the island of Kilwa Kisiwani. The 900-year-old mosque is still used for prayers, and it is visited every year by many tourists.

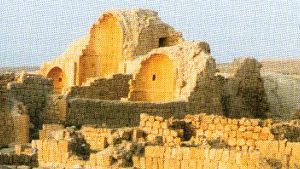

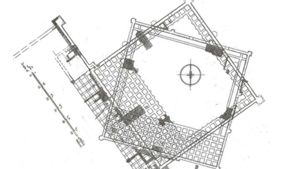

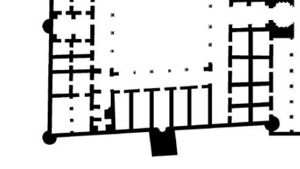

According to an inscription installed at the mosque’s mihrab, the Kizimkazi Mosque was built in 500 AH (over 940 years ago). Mihrab is a semicircular niche in the wall of a mosque that points out the qibla, the direction of the Ka’ba in Mecca, and hence the direction that Muslims should face when praying. While the inscription and some coral-carved decorations date from the time of construction, the majority of the present structure was rebuilt in the 18th century.

A similar design for the mosque’s mihrab can also be found in mosques in Tanzania and Kenya, built by Shirazi, Baluchi, Shushtari, Kazerouni, and Omani people.

The British archaeologist David Whitehouse (1941-2013), who studied in Iran and Africa, believed that the inscription in Kizimkazi Mosque is similar to the one in Siraf Port in southern Iran.

Mazunduchi Village residents, which is located near the mosque, introduce themselves as Shirazi and celebrate Noruz (Iranian New Year).

Shiraz and the southwestern coastal region of Iran are linked to the Shirazi people that inhabit the Swahili coasts of Eastern Africa.

Shirazis established Persian city-states on the eastern coast of Africa and its islands between the 13th and 15th centuries.

Origins of Persians on the East Africa shores:

The quote below is taken from: the Iranica Encyclopedia, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/east-africa

From early times monsoon winds have permitted rapid maritime travel between East Africa and Western Asia. Persian relations with the African coastal regions were largely via this maritime trade network (Hourani, pp. 4-6, 38, 79-82). Although large-scale Persian settlement in East Africa is unlikely and the only known Persian inscription in East Africa comes from an imported glazed tile, now lost, decorating a tomb at Tongoni (Freeman-Grenville and Martin, p. 116), Persian cultural and religious influences nonetheless were felt. Ki-Swahili, the language of the East African coastal regions, contains Persian loan words (q.v.), mainly nautical terms. Archeological evidence from East Africa shows economic connections with the ports of southern Persia from the 3rd to the 15th centuries C.E., and African traditional history connects the founding of some of the East African ports with Shiraz.

Sasanian interest in East Africa seems to have been largely directed toward the Red Sea and the northern coast of Somalia. Competition between Ethiopian and Persian merchants for the lucrative Indian trade may have been one cause of the Persian campaigns in Yemen during the reign of Ḵosrow I (r. 531-79), which campaigns led to Sasanian control of the Red Sea route to the Indian Ocean (Cosmas Indicopleustes apud Wolska-Conus, pp. 141, 159, 197; Procopius, de bello Persico 1.20.9-12). Persia may also have been after slaves, who in the pre-Islamic period were obtained from the Horn of Africa. Duan Chengshi, in Yuyang za zu (ca. 850 C.E.), describing an earlier period, also refers to “Possu” (probably here meaning “Persian”) merchants on the coast of Bobali (possibly northern Somalia) who formed caravans of several thousand men to obtain ivory and ambergris (Duyvendak, pp. 13-14). Before trading, these merchants were forced to draw blood and swear an oath. Persian ceramics of the 3rd/ 5th centuries C.E. have been found at the site of Ras Hafun (probably ancient Opone) in northern Somalia (Smith and Wright, pp. 125, 138-40), though 5th century ceramics, very similar to those from Ras Hafun, have been claimed from Chibuene in southern Mozambique and from the island of Ngazidja in the Comoro archipelago (Sinclair, p. 190). The 4th/10th-century Ḥodūd al-ʿālam (tr. Minorsky, pp. 163-64, with commentary), the only surviving early Persian geographical text with detained evidence on East Africa, describes the coast, termed Zangestān, as lying opposite Fārs, Kermān, and Sind; the people are described as extremely black, with curly hair and the nature of wild animals. Three towns are noted: M.ljān (possibly Unguja, the original name of Zanzibar Island), the port visited by foreign merchants; Sofāla, the royal capital, in modern Mozambique; and Hwfl (a corruption of Waqwāq?), the richest in goods. Gold is important, and ancient gold mines are well known from the basement rock complex of southern Africa (Summers, pp. 11-17, 31-104; settlement sites in the interior, such as Mapungubwe/K2, were in contact with the coast by at least the 10th century C.E. and probably much earlier (Hall, pp. 74-90).

Masʿūdī (Morūj, ed. Pellat, I, pp. 112-13, 124-25; II, p. 113), who last visited East Africa in 304⁄916 on a ship owned by two brothers from Sīrāf, suggests that regular voyages were made from Oman and Sīrāf to the Belād al-Zanj, and in particular to the port of Qanbalū (most likely Pemba Island). Masʿūdī (who was writing after the Zanj revolt) suggests ivory was the main export. Jāḥeẓ suggests (Rasāʾel, written ca. 235⁄850, para. 210-213) that many Zanj slaves came from Lanjuya (Unguja, Zanzibar Island) and Qanbalū. These claims are supported by recent archaeological work that has yielded 6th-century-C.E. radiocarbon dates from Unguja Ukuu on Zanzibar and 3rd-4th/9-10th century occupation at Ras Mkumbuu and Mtambwe Mkuu on Pemba. Other African exports were ambergris and timber, especially mangrove poles. Ebn Ḥawqal (tr. Kramers, p. 277) records that Sīrāf was built with sāj (teakwood) and other kinds of wood from East Africa.

The ports in the Lamu archipelago, though not mentioned in the literary sources, are known from archeological evidence to have also played a central part in the maritime trade. Excavations at Manda (Chittick, pp. 65-106) and Shanga (Horton, forthcoming) have produced ceramic assemblages very similar to those from Sīrāf, including numerous unglazed storage jars that were actually made in Sīrāf as well as the more widely distributed Sasanian-Islamic glazed jars and white-glazed wares. Chinese stonewares have also been found at these levels.

By the 5th/11th century the Indian Ocean trade had shifted to the ports at the head of the Persian Gulf, in particular Kīš and Hormoz (Ricks, pp. 352-55), which traded East African products to India, the Far East, and the West. In East Africa, the shift was marked by the appearance of sgraffito pottery manufactured in the Makrān. During the late 7th/13th century, the main center of the East African trade moved to the South Arabian coast. Though some Persian Gulf pottery found its way to East Africa in the 9th/15th century, by the time of Portuguese contact, East Africa was trading directly with either Aden or the ports of western India, not with the Persian Gulf itself.

Early Accounts

African traditional history recognizes early connections with the Persian Gulf. The most pervasive are stories of origin from Shiraz. The Ketāb al-solwa fī aḵbār Kelwa(BM Or. 2666; excerpts and summary in Freeman-Grenville, 1962, pp. 45ff.) tells of the voyage of seven ships manned by a father who, after a dream, left Shiraz with his six sons for East Africa, founding towns at Mandakha, Shaugu, Yanbu, Mombasa, Pemba, Kilwa, and Hanzuan. Another tradition recorded by the Portuguese in the 16th century tells of a migration of seven brothers from Laçah [al-Ḥasā in eastern Arabia], but it is unclear whether this is another version of the same story or a distinct tradition (J. de Barros, Decadas da Asia, ed. A. Baiao, Coimbra, 1930, I/8/4; trans. in Freeman-Grenville, 1962, pp. 31-32).

Chronicles from Mombasa, Vumba, and the Comoros give local elaborations of the Shirazi origin myth; the coastal peoples who claimed these origins often termed themselves “Shirazi,” and a political party—the “Afro-Shirazi” party—was formed in 1957. Explanations for this myth—no modern scholar accepts that any substantial migration took place from Shiraz—range from the extensive trade links with Sīrāf/Shiraz to religious and political factors. Allen (pp. 116-18, 179) suggests that the Shirazi myth is an Islamization of indigenous origin myths, particularly those associated with Shungwaya. Alternatively, the African courts may have looked to Buyid Shiraz as a model. Hints of this come from the descriptions of court practice and apparel. These were observed by Ebn Baṭṭūṭa in Mogadishu (pp. 179-96; tr. Defrèmery and Sanguinetti, II, pp 179-96; tr. Gibb, II, pp. 373-83), where state processions in which the ruler dressed in turban and cloak, shaded by ceremonial parasols, were preceded by a band, and followed by barefoot court officials including viziers and amirs. The Song annals (Song Shu 490, f 20 verso) describe a delegation of Africans from Zangistan who reached China in the late 11th century. The annals call the African ruler by the Buyid title Amīr-e amīrān (Chin. Ameiluo Ameilan; Hirth and Rockhill, p. 127; see AMĪR-AL-OMARĀʾ). This use of Shirazi practice may explain the observance of the Persian New Year, “Siku ya Mwaka,” on Zanzibar (Gray, 1954; 1962, p. 20), although this could equally well be linked to seafarers’ use of Now-Rūz (Nairuzi) in the navigational calendar (Tibbetts, pp. 361-66). The surviving titles such as Sheha (locally elected chief) and dīvānī (ruler) have also been cited as evidence for Persian links, but are more likely the result of the adoption of general Arabic terms for government offices by Swahili Muslims.

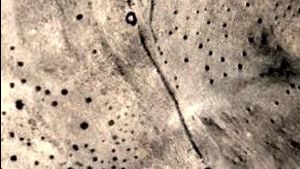

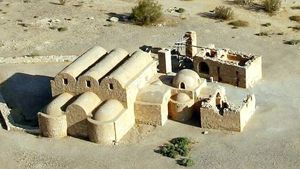

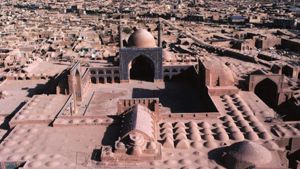

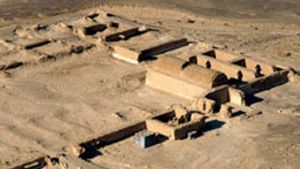

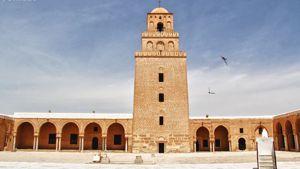

The mosque from a satellite photo

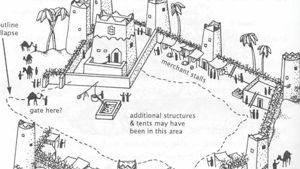

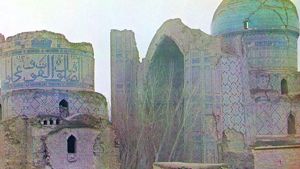

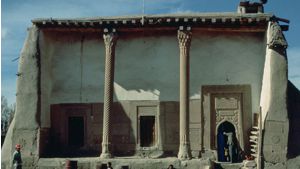

The mosque showing the mihrab nice on the left wall.

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!