An introduction to the Indian Circle, used by early Muslims to find Qibla directions. This is described to us by al-Battānī, Khwārazm, Ḥabash al-Ḥāsib and others.

Transcript

Navigation and the Qibla: Video #6

Hello, I am Dan Gibson, and welcome to the fifth video examining the question: How did the early Muslims calculate the Qibla direction? So far in this series we have had 4 instructional videos and then one discussion video. This is another lecture video, which I am now calling number 5 in the series.

So far we have examined these topics:

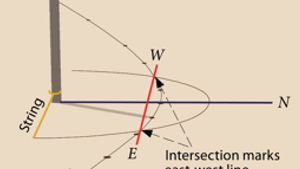

First, ‘How did the Early Arabs accurately determined the four cardinal directions?’ In that video we demonstrated a simple method that has been used for thousands of years to accurately establish the four cardinal directions.No complex math was involved. A post was driven into the ground, and the shadow followed for several hours to mark a true east-west line. A circle was added and the North-South line added.

In the second video we examined the Arab Windrose or the 32 direction Arab compass used for telling direction and demonstrated how these 32 directions could be added to the circle on the ground.

Third we examined the topic: ‘How the early Arabs measured distance?’We looked at various methods that were used, especially that of counting steps as the merchant caravans crossed the deserts.This practice was noted by Roman historians who saw it and noted it down.

In the fourth video we looked at the mindset of the Arab caravan merchant, always measuring the distance he had traveled, counting his steps, and then calculating the direction he had traveled, and the direction to his next destination.

Then there was a discussion video with three other men who had a background in navigation and who could understand and share about what I was lecturing on.

Now in this video we want to see how navigational techniques were used by mosque builders to accurately determine the Qibla direction. Again, no complex math was involved.

Notice that I use the word ‘navigation.’ I am not referring to ‘astronomy’ and ‘mathematics’ that the later Muslims excelled in. These are slightly different sciences as we will see.

Some of you are aware of the strong position that Dr. David A. King has taken against my measurements of early Islamic Qiblas. Dr. King has written several hundred papers and articles, in his life, and some of his papers have also been compiled into several books.

In all of his writing, Dr. King mentions the navigators of Islam, only a couple of times. For instance when speaking of Gerald R. Tibbetts’s translation of Ibn Majid and Sulayman al-Mahri. King emphatically states that Arab navigation was an aspect of what he calls ‘Islamic folk astronomy’ and not of the science of astronomy, which is based on what he calls ‘observations and calculations.’

Dr. King argues that the great scientist of the Medieval era were astronomers and mathematicians, not navigators. He admits that he only mentions two navigators such as Ibn Majid and Sulayman al-Mahri in passing.

The astronomical lore of the Arab navigators is perhaps best understood as a branch of this folk astronomical tradition. Most of what we know about it is contained in the writings of two South Arabian navigators from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Ibn Majid and Sulayman al-Mahri. Their major works have been published from the few available manuscripts by I. Khoury and a particularly valuable study of them has been prepared by G. R. Tibbetts.

King continues: In general, the Muslim astronomers had little interest in the folk tradition, although from the ninth century onwards it was well documented and readily available to them. But they never even mention the astronomy of the navigators.

King is pointing out here that in medieval times there were two groups: 1) astronomers and mathematicians on one side and 2) the navigators and those doing folk astronomy on the other side. And they didn’t communicate much with one another.

So Dr King has studied one stream: astronomers and mathematicians, and that is where he excels. He is an expert there. On the other hand, I have studied the techniques used by the navigators. In the ancient Islamic world the astronomers and the navigators ignored each other and some times said despairing things about each other. On one side, the astronomers had access to the newly translated Greek books that were transforming the Arab view of astronomy and mathematics. The navigators on the other hand were old school holding to old ideas and traditions.

Now, during the last few months I have slowed down the making of YouTube videos, as I have concentrated on reading the medieval Islamic astronomers and geographers, the very ones that Dr. King reads.

You see, I think Dr. King has not only studied the science of the medieval writers, (astronomers and mathematicians) he seems to have embraced their attitudes towards the navigators. For example in his review of my book: Early Islamic Qiblas he states:

He (Gibson) also introduces the Arab windrose, but this was used only in Arab navigation, certainly not for finding the qibla to Mecca …Pg 362

I don’t find this kind of statement helpful. As far as I can see, everything the navigators did was part of a system of techniques to allow the merchant navigators to arrive at a distant point over the horizon.

It was all about picking a point on the horizon and then saying “the city we want to go to is there, and how do I navigate to that spot.”That is what the Qibla was all about. I want to build a mosque here and I want to face a distant spot over the horizon.

That was the whole purpose of their navigational techniques. And determining the Qibla direction was exactly the same problem and was done with the same navigational tools and methods. That is why I turn to the navigators not the astronomers to discover how the Qibla was determined in the first years of Islam.

Dr. King goes on to complain about my research. He says:

Gibson’s bibliographical citations throughout the book leave a lot to be desired … On the history of Islamic astronomy and mathematics there is not a single item…

Exactly, since I am coming from the navigator’s point of view, why should I quote the astronomers who were writing hundreds of years later using the new sciences that they learned from Greek sources? Dr. King seems to have unwittingly fallen into the pull and tug between ancient Arab navigators on one side and the astronomers and mathematicians on the other.In his paper:Folk Astronomy in the Service of Religion: The Case of Islam (Astronomies and Cultures),King boldly states:

The astronomical lore of the Arab navigators is perhaps best understood as a branch of this folk astronomical tradition… The only practical device used by the Arab navigators besides the compass was the kamal, a simple knotted rope for determining latitudes by means of the Pole Star.

A little later he states:

The early navigators developed all that they required of this practical science and, (before the Ottoman period at the beginning of the sixteenth century), borrowed nothing from the scientific tradition.

Dr. King attacks me again in his paper: From Petra back to Mecca: when he states:

Gibson imagines that qibla determinations “came out of early navigation’’, neglecting to say precisely what documents he means, where he found these documents, or precisely what he found in them. Nonetheless he makes his imaginings into a personal truth, but it surely doesn’t rise to the level of scholarship. All rather Trumpish. I know of no such documents.

That is interesting, because he does know.I am going to quote the very same sources he does.

As I said, during this last month I began to dig further into the medieval astronomers and mathematicians that I had only considered previously with a cursory study. But during the last 8 weeks I made an interesting discovery. Dr. King is fully aware of how the early Muslims calculated their Qibla. He has read it, he has mentioned it several times in his papers, and then he has dismissed because he says it is unreliable. So in our next video we are going to look at how unrealizable it was. We are going to use the early method and then test it going east and west to see how accurate or inaccurate it was.

I am referring to a method of Qibla finding that is described by several of the medieval astronomers. The Syrian astronomer al-Battani, wrote from the Islamic city of Raqqa around 297 AH (910 CE) and he described an early method of determining the Qibla. Other writers also touch on this topic, such as Khwarazm Habash al-Hasib, (Baghdad, ca 825 to 835) recorded a similar method, but then he added many more calculations to try and make it more accurate. (King, D. A., (Astronomy in Islamic society, 1996, page 144 /17)

Now I have al-Battani’s book here beside me. It is a fascinating book. It was written a long time ago. Al-Battani mentions an explanation. Dr. King describes it, so lets let Dr. King give us a description.

This is from Chapter 4 called Chapter 4, Astronomy and Islamic society first published in 1996 on page 143. Dr. King writing:

Another approximate method, mentioned by al-Battani, was widely used and remained popular until the nineteenth century. The method could not be simpler. First draw a circle on a horizontal plane and mark the cardinal directions

This is exactly what we did in the first two videos. Then we mark out the degrees on the circle.

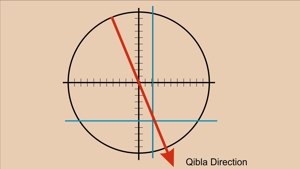

Then draw a line parallel to the north-south line and at an angular distance - measured on the circle - equal to the longitude difference between Masjid al-Haram and the new locality and another line parallel to the east-west line at an angular distance equal to the latitude difference. Then the line joining the centre of the circle to the intersection of these two tines defines the qibla.

There is an illustration of what Al-Battani is saying. Let’s start again from the beginning in case you missed the first videos:

Begin with a large flat horizontal surface where you want to build.

Pound a wooden stick into the ground in the center. The larger the better.

Mark the shadows of the stick as it moved throughout the day.

Draw a line through the mark. This is the east-west line.

Then use two arcs drawn on the line to mark the cross line. This is the north-south line.

Then mark the circle onto the ground with a rod.

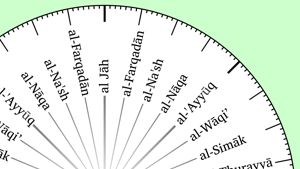

Then mark measurements around the circle.224 of them equally spaced. Use overlapping identical circles to locate the centerline.

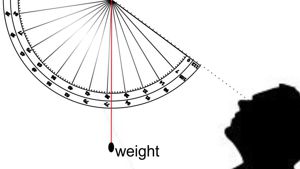

Then measure down from the center of the circle the number of zams that the North Pole is above the location where you want to build. Then draw a horizontal line at that spot.The Qibla will be somewhere along that line.

Then the hard part. Mark the number of zams on the east west line that indicate the number of Zams the new building will be from Masjid al-Haram.

Then draw a line from the center of the circle to where the two lines intersect, and that is your qibla angle.

Does this sound familiar? This is exactly what we have been describing in this video series. al-Battani doesn’t explain how every step was made, but he draws the very same chart that we have been drawing in this video series. He tells us it must be drawn on the ground.

Now, in this video I am going to call this method the Indian Circle. That is a name that was used many centuries later to describe this method. The method used in the Indian Circle existed long before as an old navigational tool. We don’t know who first made it. Did it start with Arabs who later sailed to India, or with Indian merchants to later had contact with Arabia? Was it first used in the deserts of Arabia, or did it originate in India. We have no idea.All we know is that hundreds of years after the founding of Islam, it was called the Indian Circle, so that is what we will call it, so you can Google it and find it.

So, how accurate was this method?

The first 8 steps could be done with great precision. The larger the circle and the taller the post, the more accurate it became. So you would want to drive in a large post, and make a very large circle around it so that the shadow of the top of the post could be traced inside the circle.

There is a record that the Abbasid Caliph Ma’mun (ca. 830 CE) became obsessed with accuracy, and so he asked his scientists to make some very accurate measurements. The larger the better. There are several records which tell us of two experiments. These are recalled by lbn Yunus (990 CE) and al-Biruni (1025), also Yahya ibn Akthan, (Around 830 CE), the judge appointed by Caliph Ma’mun mentions it, and a contemporary astronomer Habash al-Hasib, (around 825) So these two experiments are well attested to.

lbn Yunus recounts:

*Ma’mun … asked him to measure the amount of one degree of a great circle on the surface of the earth. He said: “We both set off together for this (purpose). He ordered ibn ‘AliIbn ‘Isa al-Asṭurlabi and ‘Ali ibn Buhturi to do the same and they went off in a different direction. Sanadibn‘Ali said: “Khalid ibn ‘Abd al-Malik and I travelled to between W’m*ah and (Palmyra) and there we measured the amount of a degree of a great circle on the surface of the earth. It was fifty-seven miles (al-mil or Arabic mile). ‘Ali ibn ‘Isa and ‘Ali ibn al-Buhturi also made measurements and the two of them found the same as this. The two reports from the two directions, the two measurements with the same result arrived at the same time.**(The Arabic letter at this place has no dot, so it could have been a b, n, or ir even a ya.)

On an interesting note, around 830 AD, Caliph Al-Ma’mun also commissioned a group of Muslim astronomers and Muslim geographers to measure the distance from Palmyra to Raqqa, in modern Syria. They found the cities to be separated by one degree of latitude and the meridian arc distance between them to be 66⅔ miles and thus calculated the Earth’s circumference to be 24,000 miles.(Actually it is 24,901 miles), so they were only out by 901 miles, which was more accurate than most astronomers had been up until that time.

Then the second group of scientists headed east of Baghdad, al-Biruni cites Habash:

The observations commissioned by al-Ma’mun took place only when he had read in the books of the Greeks that the equivalent hissa of one degree was five hundred stades, which is the unit of theirs that they used for measuring distances, but he did not find amongst the Arab translators sufficient knowledge about its length compared with known units.

At that time - according to what Habash related a group of scholars of instrument construction and expert constructors from amongst the carpenters and brass-workers - Al-Ma’mun ordered the construction of instruments and the selection of a place for this survey. There was chosen a location in the desert of Sinjar between the area of Mosul and Samarra, where they were satisfied that the ground was level. They transported the instruments there and they selected a place where they observed the solar altitude at midday. Then two groups set forth (in two different directions). Khalid and a group of surveyors and instrument-makers headed in the direction of the northern pole, and ‘Ali ibn ‘Isa al-Asturlabi and Ahmad ibn al-Buhturi the surveyor with another group towards the south pole. Each of the two groups observed the altitude of the sun at midday until they found that it had changed by one degree, apart from the change that resulted in the solar declination. They measured the track on their way out and set up markers with arrows) as they went, and as they returned they investigated the distance for the second time. The two groups met again at the place from which they had set out, and they found that one degree of the terrestrial meridian is equivalent to fifty-six miles. Habash claimed that he had heard Khalid dictating that number to the Qadi Yahya ibn Aktiam.

So the Arabs at the beginning on the Abbasid era were obsessed with establishing accurate measurements. They were aware of the old methods of calculating direction used by the navigators, using zams, but now they were interested in establishing new mathematical methods that were much more accurate at greater distances, using Greek or other measurements and new maths.

Remember, the new astronomers and mathematicians were gaining knowledge and ideas from literature written in Greek. Greek was not just the language of the Greeks but it was also the language of the educated in the Roman Empire that followed. During the time of al-Ma’mun the library in Baghdad was filling up with books that were translated from these Greek sources. And these new astronomers and mathematicians were captivated with the new sciences.

Now there was an important occurrence at this time. The new sciences embraced the geometry of the Greeks, and the Greeks used 360 degrees in their circles just as the Babylonians did.

The astronomers and mathematicians spurned the old navigators with their old system of 224 degrees in a circle. That was old school and they had nothing more to do with it. And so the division between the astronomers and the navigators widened even more. The old techniques stayed alive only among the navigators who still found the old methods to be useful to do rudimentary navigation. And so you will find virtually nothing about the techniques of the navigators in the writings of the astronomers and mathematicians. They don’t use the same units of measurement, nor even the same number of degrees in a circle. That is why my explanation uses 224 degrees and measurements called zams.

Now let’s have a look at the last steps of al-Battani’s Indian Circle.

The mosque architect has added all 224 degrees to his circle. Next he then counts out how far north or south Masjid al Haram is… counting in zams.At that point he draws a horizontal line across the circle.He knows the location of Masjid al Haram as Arab Merchants calculated it centuries before, and now Muslims would have memorized this number for many years.Every Muslim visiting near the original Holy city of Islam, could measure the height of the North Pole star using his or her fingers. The kids would all want to try, to see how close their measurements were to the official number.

Now that the mosque builder is in a new location, not at the Sacred City, he then determines his new zam position. The circle on the ground represents the new location, so now he wants to plot the Sacred City onto that circle.

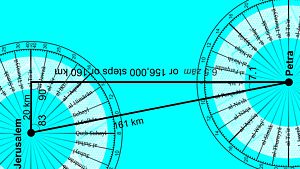

Let’s imagine that the new mosque is to be built in Jerusalem. The architect would measure the height of the North Star at 17 ‘isba and 4.5 zams, or a total of 123.4 zams.He would know that the height of the North Star in Petra would be 16 ‘isba 5 zams or 117 zams. So the difference is 6.5 zams. That is equal to 156,000 steps. (168 km is one zam, and 8 zams or 1,344 km travel to the north would raise the north pole 1 ‘isba.

Now all he needed to do is measure the difference between the two locations and chart it on his circle. Measuring the horizontal line on the circle is just a matter of entering in the number of zams for the Holy City and drawing a horizontal line.

The next step is determining how far east or west he is. Many of the early maps I have seen use the city of Alexandria as the focal point. Today the British use Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) because the counting starts in Greenwich in the UK. In ancient time, the circle of the earth was most often calculated from Alexandria, the location of the original Alexandrian Library and Museum established around 250 BCE. Ever since then Alexandria has been one of the main places that direction and distance was measured from. For the Nabataean merchants, Alexandria was the closest large port city that dealt directly with Rome. It makes sense that they would measure from Alexandria, and used this for many centuries.

So from Alexandria to Petra it was 3.2 zams and a little bit or 540 km. The architect would measure just over 3.2 zams and draw a line vertically downwards.Where the two lines crossed marked the Qibla. The Qibla direction was represented by the line from the post out to the Qibla.

As long as the Arabs kept good track of east west distances the Indian Circle could accurately determine the Qibla direction within a degree or two. Remember the Arabs had been measuring the distances from 250 BCE to 500 CE which is some 750 years of checking and double checking their distances!

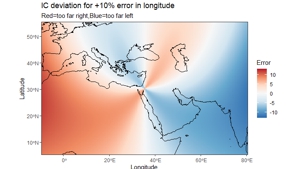

There are only two places that this system could err. One is if there was something wrong with the concept of the Indian circle, which there was, because it did not take into consideration the curvature of the earth. But how much would that affect the outcome? We will find out in the next video.

The other place of possible error was if the Arabs counted the distance east or west wrongly. And we are going to test that out in the next video as well.

I am Dan Gibson and this has been another video in the series Navigation and the Qibla

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!