The Nabataean people began emerging from the Arabian Desert about the same time that Ptolemy I Soter became the ruler of Egypt. At first these emerging civilizations clashed with one another, but within a few short years they began forming trade alliances and cultural exchanges. The Ptolemies needed access to eastern trade, and the Nabataeans needed access to the markets on the Mediterranean. Their mutual cooperation resulted in a complete shift of power in the Middle East. Alexandria became the richest trading city in the Mediterranean world, and the Nabataeans became the richest tribe in Arabia. As long as the Ptolemies and later the Romans allowed the Nabataeans to continue their merchant trade in peace, the Nabataeans allowed the Ptolemies to equally grow rich from the proceeds of trade.

As one examines the history, culture and advancements of the Ptolemies, similar history, culture and advancements can be observed in the Nabataean civilization. In fact, the Nabataeans adopted more from the Ptolemaic culture than from any of the other cultures and civilizations that they came in touch with.

Parallels can be seen in the Nabataean development of coins, brother/sister marriages, architecture, massive construction projects, trade agreements (making Alexandria and Petra world class trade centers), deifying their great dead kings (Ptolemy I, Obodas I and Aretas III), clothing styles, and even their methods of burying the dead. In this paper we will first examine Ptolemaic history, and then we will examine some of the things that the Nabataeans adopted from them.

Historical Overview

The Ptolemaic Dynasty began with one of Alexander the Great’s generals who was given rule over Egypt. This Macedonian general and his descendants ruled Egypt during the Hellenistic period, from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC until Egypt became a Roman province in 30 BC. At various times the Ptolemies also controlled Cyrenaica (now north-eastern Libya), parts of Palestine, and Cyprus. Their dynasty was founded by Alexander’s general, Ptolemy. Named governor of Egypt by Alexander, he established himself as an independent ruler in 305 BC, adopting the name Ptolemy I Soter. The kingdom prospered under him and his successors, Ptolemy II Philadelphus and Ptolemy III Euergetes, who vied with another Macedonian dynasty, the Seleucids of Syria, for supremacy in the eastern Mediterranean.

The capital of the Ptolemaic state was Alexandria, a major city and sea port on the Mediterranean. This city had large Greek and Jewish populations and quickly became one of the great commercial and intellectual centers of the ancient world. Although not of Egyptian origin, the Ptolemies kept many of Egypt’s customs. They had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and they participated in Egyptian religious rituals. They also preserved Egypt’s ancient architectural traditions, erecting temples to the Egyptian gods at Edfu, Dendera, and other places. The recent discovery of many papyri has enabled historians to reconstruct a picture of what life was like under the Ptolemies. They established major administrative, financial, and commercial infrastructures, including the most advanced system of banking in the ancient world. Most of the land belonged to the state which rented it out to the people. Although the state provided seed corn, it required to be repaid in kind at harvest time. They also established the world’s major centers of learning and culture. The library and museum in ancient Alexandria were immensely famous and brought the city to the focus of academic attention.

The power of the Ptolemy dynasty declined under a succession of weak kings in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, when Rome began to intervene increasingly in Egyptian affairs. The last and probably the most famous Ptolemaic ruler was Cleopatra, who ruled independently first through the support of Julius Caesar and later that of Mark Antony. With her death and that of her son, Ptolemy XV, (called Caesarion), in 30 BC, the dynasty came to an end, and Egypt was annexed to the Roman Empire by Augustus.

Ptolemy I

Ptolemy I (367-283 BC), called Ptolemy Soter (“preserver”) was king of Egypt (323-285 BC) and founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Soter was the son of nobleman Lagus, a Macedonian of common birth and of Arsinoe, who was related to the Macedonian Argead dynasty.

He was probably educated as a page at the royal court of Macedonia, where he became closely associated with Alexander. He was exiled in 337, along with other companions of the crown prince. When he returned, after Alexander’s accession to the throne in 336, he joined the King’s bodyguard, took part in Alexander’s European campaigns of 336-335, and in the fall of 330 was appointed personal bodyguard (somatophylax) to Alexander; in this capacity he captured the assassin of Darius III, the Persian emperor, in 329. He was closely associated with Alexander during the advance through the Persian highland. As a result of Ptolemy’s successful military performance on the way from Bactria (in northeastern Afghanistan) to the Indus River (327-325), he became commander (trierarchos) of the Macedonian fleet on the Hydaspes (modern Jhelum in India). Alexander decorated him several times for his deeds and married him to the Persian Artacama at the mass wedding at Susa, the Persian capital, which was the crowning event of Alexander’s policy of merging the Macedonian and Iranian populations.

Ptolemy, who distinguished himself as a cautious and trustworthy troop commander under Alexander, also proved to be a politician of unusual diplomatic and strategic ability in the long series of struggles over the throne that broke out after Alexander’s death in 323. Convinced from the outset that the generals could not maintain the unity of Alexander’s empire, he proposed during the council at Babylon, which followed Alexander’s death, that the satrapies (the provinces of the huge empire) be divided among the generals. He became satrap of Egypt, with the adjacent Libyan and Arabian regions, and methodically took advantage of the geographic isolation of the Nile territory to make it a great Hellenistic power. He took steps to improve internal administration and to acquire several external possessions in Cyrenaica (the easternmost part of Libya), Cyprus, and Syria and on the coast of Asia Minor. These, he hoped, would guarantee him military security.

In 322 Ptolemy, taking advantage of internal disturbances, acquired the African Hellenic towns of Cyrenaica. In 322-321, as a member of a coalition of “successors” (diadochoi) of Alexander, he fought against Perdiccas, the ruler (chiliarchos) of the Asiatic region of the empire. The coalition was victorious and Perdiccas died during the fighting. Ptolemy’s diplomatic talent was put to the test during this war. When the satrapies were redistributed at Triparadisus in northern Syria, Antipater, the general of the European region, became regent of the Macedonian empire and Ptolemy was confirmed in possession of Egypt and Cyrene. He further strengthened his position by marrying Eurydice, the third daughter of Antipater.

About 317 he married Berenice I, the granddaughter of Cassander, the son of Antipater. Cassander, at his father’s death in 319 refused to accept his father’s successor, made war upon him, seized part of the empire, and in 305 assumed the title of king of Macedonia. In the coalition war of 315-311, Ptolemy obtained possession of Cyprus. In this war he scored his most important victory in the battle near Gaza in 312, in which the Egyptian contingents were decisive. But war broke out anew in 310, and he lost Cyprus again in 306. He temporarily lost Cyrene as well and was unable to hold the important Greek positions of Corinth and neighboring Sicyon and Megara, which he had captured in 308. He ultimately suffered overwhelming defeat in 306 in the naval battle near Salamis on Cyprus. The victor in this battle, Antigonus I Monophthalmus, who was assisted by his son, Demetrius Poliorcetes, assumed the title of king in 306. The remaining satraps, led by Ptolemy after he successfully resisted Antigonus’ attack on Egypt, also took the title of king in 305-304.

Ptolemy was prevented from holding Cyprus and parts of Greece, and he resisted invasions of Egypt and Rhodes and occupied Palestine and Cyrenaica. In 305 BC he assumed the title of king of Egypt. Alexandria was declared his capital, and he soon founded the Library of Alexandria.

King of Egypt

After naming himself king, Ptolemy’s first military concern was the continuing war with Antigonus, which was now focused on the island of Rhodes. In 304 Ptolemy aided the inhabitants of Rhodes against Antigonus and was accorded the divine title Soter (Saviour), which he was commonly called from that time. The dissolution of Alexander’s empire was brought to a close with the battle near Ipsus in Asia Minor in 301. During this battle Antigonus was defeated by the other kings. This led to the attempt by the remaining successors of Alexander to define their kingdoms. For this reason a dispute arose between Ptolemy and Seleucus I Nicator of Babylon over Syria, particularly the southern Syrian ports, which served as terminal points for the caravan routes. This quarrel, however, was temporarily settled peacefully through compromise. In addition to Coele Syria (Palestine), Ptolemy apparently also occupied Pamphylia, Lycia, and part of Pisidia in southern Asia Minor.

During the last 15 years of his reign, because of the defeats he suffered between 308 and 306, Ptolemy preferred to secure and expand his empire through a policy of alliances and marriages rather than through warfare. In 300 he concluded an alliance with Lysimachus of Thrace (modern Bulgaria) and gave him his daughter Arsinoe II in marriage in 299⁄298. At approximately the same time he married his stepdaughter Theoxena to Agathocles, the tyrant of Syracuse (southeastern Sicily). About 296 he made peace with Demetrius Poliorcetes, to whom he betrothed his daughter Ptolemais. To Pyrrhus of Epirus, Demetrius’ brother-in-law, who was at the Egyptian court as a hostage, he gave his stepdaughter Antigone. He finally brought rebellious Cyrene into subjection in 298, and in approximately 294 he gained control over Cyprus and the Phoenician coastal towns of Tyre and Sidon.

In a last coalition war in 288-286, in which Ptolemy, Seleucus, Lysimachus, and Pyrrhus opposed Demetrius, the Egyptian fleet participated decisively in the liberation of Athens from Macedonian occupation. During this war Ptolemy obtained the protectorate over the League of Islanders, which was established by Antigonus Monophthalmus in 315 and included most of the Greek islands in the Aegean. Egypt’s maritime supremacy in the Mediterranean in the ensuing decades was based on this alliance.

Ptolemy was able to evaluate the chaotic international situation of this post-Alexandrian era, which was characterized by constantly renewed wars with shifting alliances and coalitions, in realistic political terms. Adhering to a basically defensive foreign policy, he secured Egypt against external enemies and expanded it by means of directly controlled foreign possessions and hegemonic administrations. He did not, however, neglect to devote attention to the internal organization of the country and to provide for a successor. In 290 he made his wife Berenice queen of Egypt and in 285 (possibly on June 26) appointed his younger son Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who was born to Berenice in 308, co-regent and successor. The provision for the succession, which was based on examples from the time of the pharaohs, made possible a peaceful transition when Ptolemy died in the winter of 283-282. The early Ptolemies were occupied with the economic exploitation of Egypt, but, because of the lack of first-hand information, the details of Ptolemy’s participation in the process cannot be determined. It is certain, however, that discrimination against the Egyptians took place during his reign. The only town he founded was Ptolemais in Upper Egypt. He probably placed Macedonian military commanders alongside the Egyptian provincial administrators and intervened unobtrusively in legal and financial affairs. In order to regulate the latter, he introduced coinage, which until that time was unknown in Egypt.

He found it necessary from the outset, however, to pursue a conciliatory policy toward the Egyptians, since Egyptians had to be recruited for his army, which initially numbered only 4,000 men. Ptolemy won over the Egyptians through the establishment in Memphis of the Sarapis cult, which fused the Egyptian and Greek religions; through restoration of the temples of the pharaohs, which had been destroyed by the Persians; and through gifts to the ancient Egyptian gods and patronage of the Egyptian nobility and priesthood. Finally, he founded the Museum (Mouseion), a common workplace for scholars and artists, and established the famous library at Alexandria. Besides being a patron of the arts and sciences, he was a writer himself. In the last few years of his life Ptolemy wrote a generally reliable history of Alexander’s campaigns. Although it is now lost, it can be largely reconstructed through the extensive use made of it later by the historian Arrian.

Several times during his life Ptolemy was proclaimed a deity by certain classes of people. After his death he was raised to the level of a god by all the Egyptians.

Ptolemy II

Ptolemy II (309-246 BC) was commonly called Ptolemy Philadelphus (“brotherly”), king of Egypt (285-246 BC). He was one of the younger sons of Ptolemy I by his wife Berenice I who died before 283 BC. Ptolemy II was perhaps the most important Egyptian ruler when we consider the history of the Nabataeans.

During his wars with the Seleucid king Antiochus I, he established Ptolemaic Egypt as the dominant maritime power in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. The economy of Egypt was brought under government control and the cultural life at the Alexandrian court flourished. The Greek poets Callimachus and Theocritus were among the literary figures connected with the court. Ptolemy II increased the number of books in the Library of Alexandria and was an active patron of literature and scholarship. He continued his father’s dream of collecting all the known knowledge and wisdom of the civilizations of the world, and so authorized many sailing expeditions to travel to far shores in search of wisdom.

He also extended his power by skillful diplomacy, developed agriculture, and commerce, and made Alexandria a leading centre of the arts and sciences. Reigning at first with his father, Ptolemy I Soter, he became sole ruler in 283-282 and purged his family of possible rivals. This dynastic strife led also to the banishment of his first wife, Arsinoe I, daughter of King Lysimachus of Thrace. Ptolemy then married his sister, Arsinoe II, an event that shocked Greek public opinion but was celebrated by the Alexandrian court poets. Taking advantage of the difficulties of the rival kingdoms of the Seleucids and Antigonids, Ptolemy II extended his rule in Syria, Asia Minor, and the Aegean at their expense and asserted at the same time his influence in Ethiopia and Arabia. Egyptian embassies sent to Rome as well as to India reflect the wide range of Ptolemy’s political and commercial interests.

While a new war with the Seleucids (from 274 to 270 BC) did not affect the basic position of the rival kingdoms, the so-called Chremonidean War (268?-261 BC), stirred up by Ptolemy against Antigonus II Gonatas, king of Macedonia, resulted in the weakening of Ptolemaic influence in the Aegean and brought about near disaster to Ptolemy’s allies Athens and Sparta. Ptolemy was no more successful in the Second Syrian War (260-253 BC), fought against the coalition of the Seleucid king Antiochus II and Antigonus Gonatas. The unsuccessful course of the military operations was compensated for, to a certain degree, by the diplomatic skill of Ptolemy, who first managed to lure Antigonus into concluding a separate peace (255) and then brought the war with the Seleucid Empire to an end by marrying his daughter, Berenice–provided with a huge dowry–to his foe Antiochus II. The magnitude of this political masterstroke can be gauged by the fact that Antiochus, before marrying the Ptolemaic princess, had to dismiss his former wife, Laodice. Thus freed for the moment from Seleucid opposition and sustained by the considerable financial means provided by the Egyptian economy, Ptolemy II devoted himself again to Greece and aroused new adversaries to Antigonid Macedonia. While the Macedonian forces were bogged down in Greece, Ptolemy reasserted his influence in the Aegean, making good the setback suffered during the Chremonidean War and establishing Egyptian naval predominance in the region. He further improved his position by arranging for the marriage of his son (and later successor) Ptolemy III Euergetes to the daughter of King Magas of Cyrene, who had proved so far a very troublesome neighbor. Not aiming at outright hegemony (even less imperialistic conquest) in the Hellenistic world of the eastern Mediterranean, Ptolemy II tried nonetheless to secure for Egypt as good a position as possible, holding at large his rivals beyond a wide buffer zone of foreign possessions. Without being completely successful, he managed to let his allies bear the brunt of the heaviest reverses, healing his own military wounds with diplomatic remedies. The influence on Ptolemy of his wife and sister Arsinoe II, particularly in foreign affairs, was certainly substantial, though not as extensive as claimed by some contemporary authors.

Ptolemy II’s record in domestic affairs is no less impressive. From pharaonic times onward, agriculture and the work of artisans in Egypt had been highly organized. Under Ptolemy’s supervision and with the help of Greek administrators, this system developed into a kind of planned economy. The peasant masses of the Nile Valley provided cheap labor, so that the introduction of slavery on a broad basis was never considered an economic necessity in Ptolemaic Egypt. Ptolemy II became a master at the fiscal exploitation of the Egyptian countryside; the capital, Alexandria, served as the main trading and export centre. Ptolemy II displayed a vivid interest in Greek as well as in Egyptian religion, paid visits to the sanctuaries in the countryside, and spent large sums erecting temples. Anxious to secure a solid position for, and religious elevation of, his dynasty, the King insisted upon divine honors not only for his parents but also for his sister and wife Arsinoe II and himself as theoi adelphoi (“brother gods”). He thus became one of the most ardent promoters of the Hellenistic ruler cult, which in turn was to have a far-reaching influence on the cult of the Roman emperors.

Under Ptolemy II, Alexandria also played a leading role in arts and science. Throughout the whole Mediterranean world the King acquired a reputation for being a generous patron of poets and scholars. Surrounding himself with a host of court poets, such as Callimachus and Theocritus, he expanded the library and financed the museum, a research centre founded as a counterweight to the more antimonarchical Athenian schools. Learning there was not confined to philosophy and literature but extended also to include mathematics and natural sciences. (A review of this is given in the paper: Alexandria) The age of Ptolemy II coincided with the apex of Hellenistic civilization; its vigor and glamour were a result of the still fresh forces of Greek leadership in the eastern Mediterranean. Ptolemy II was no man of peace, but neither was he one of the warlike Hellenistic soldier-kings. A prudent and enlightened ruler, he found his strength in diplomatic ability and his satisfaction in a vast curiosity of mind. Under his direction astronomy and navigation by stars reached new heights. Maps of the world were compiled, and exotic goods from many of the far corners of the world found their way to Alexandria, many of them through the hands of ‘Arab’ merchants.

Ptolemy II scandalized the Greeks by marrying his own sister, Arsinoe. While the Greeks viewed this as incest, brother-sister marriages were a custom of the Egyptian pharaohs and the Ptolemies simply continued the tradition for generations. Ptolemy II added insult to injury when he minted a new coin with himself and his sister-queen, Arsinoe, on one side and his parents on the reverse. The legend on the coin referred to his parents as ‘gods’ and to Ptolemy II and Arsinoe as the “divine siblings.” These coins were also struck by the successors of Ptolemy II.

The queens of the Ptolemaic dynasty were often powerful and influential. Arsinoe II had been previously married to Lysimachos of Thrace and later to her half-brother, Ptolemy Keraunos, before her marriage to Ptolemy II. Known for her intelligence and ambition, she is credited with influencing her husband’s foreign affairs. Thus it is not surprising to discover that the Nabataean rulers were attracted to her, and they eventually also practiced brother/sister marriages as well as the act of deifying some of their leaders. When she died suddenly in 269 B.C., Ptolemy II established a state cult for her and issued coins with her portrait.

Ptolemy’s mother, Berenike, did not participate in public affairs but her influence was nevertheless significant. It was her son, rather than Ptolemy’s first-born son by his previous marriage, who succeeded to the throne, and after her death she received her own temple at Alexandria, near the temple where she and Ptolemy were worshipped together as Savior gods. The Red Sea port of Berenike, often frequented by Nabataean merchants, also bears her name.

Ptolemy III

Ptolemy III (282-221 BC) was known as Ptolemy Euergetes (“benefactor”), and was king of Egypt from 246-221 BC. He was the son of Ptolemy II and he reunited Cyrenaica with Egypt, as well as invaded the Seleucid Kingdom of Syria to avenge the murder of his sister and her infant son, the heir to the Seleucid throne. As a ruler, Ptolemy III was a liberal patron of the arts and added extensively to the Museum and Library of Alexandria. His rule marked the height of Egyptian power, prosperity, and wealth under the Ptolemies.

Almost nothing is known of Ptolemy’s youth before 245, when, following a long engagement, he married Berenice II, the daughter of Magas, king of Cyrene; thereby he reunited Egypt and Cyrenaica, which had been divided since 258. Shortly after his accession and marriage, Ptolemy invaded Coele Syria, to avenge the murder of his sister, the widow of the Seleucid king Antiochus II. Ptolemy’s navy, perhaps aided by rebels in the cities, advanced against Seleucus II’s forces as far as Thrace, across the Hellespont, and also captured some islands off the Asia Minor coast, but were checked c. 245. Meanwhile, Ptolemy, with the army, penetrated deep into Mesopotamia, reaching at least Seleucia on the Tigris, near Babylon. According to classical sources he was compelled to halt his advance because of domestic troubles. Famine and a low Nile, as well as the hostile alliance between Macedonia, Seleucid Syria, and Rhodes, were perhaps additional reasons. The war in Asia Minor and the Aegean intensified as the Achaean League, one of the Greek confederations, allied itself to Egypt, while Seleucus II secured two allies in the Black Sea region. Ptolemy was pushed out of Mesopotamia and part of North Syria in 242-241, and the next year peace was finally achieved. Ptolemy managed to keep the Orontes River region and Antioch, both in Syria; Ephesus, in Asia Minor; and Thrace and perhaps also Cilicia.

Within Egypt, Ptolemy continued the colonization of al-Fayyum (the oasis-like depression southwest of Cairo), which his father had developed. He also reformed the calendar, adopting 311 as the first year of a “Ptolemaic Era.” The Canopus decree, a declaration published by a synod of Egyptian priests, suggests that the true duration of the year (365 ¼ days) was now recognized, for an extra day was added to the calendar every four years. The new calendar failed, however, to achieve popular acceptance. The priests and classical sources also credited Ptolemy with the restoration of the divine statues plundered from the temples during Persian rule. In addition, the King initiated construction at Edfu, the Upper Egyptian site of a great Ptolemaic temple, and made donations to other temples.

Ptolemy avoided involvement in the wars that continued to plague Syria and Macedonia. He did, however, send aid to Rhodes, after earthquakes devastated the island, but he refrained from subsidizing the schemes of the Spartan king against Macedonia, though he granted him asylum in 222. In Asia Minor, when a pretender to one of the kingdoms, who was the instigator of much of the trouble there, sought asylum in Ptolemaic territory, Ptolemy promptly interned him. His policy was to maintain an equilibrium of power, guaranteeing the safety of his own territory. After declaring his son his successor, Ptolemy died, leaving Egypt at the peak of its political power, and internally stable and prosperous. Ptolemy III’s reign is discussed in W.W. Tarn’s Hellenistic Civilisation (3rd ed., 1952) and in the first volume of A. Bouche Leclercq’s Histoire des Lagides (1903).

Ptolemy IV

Ptolemy IV (221 BC - 205 BC) was known as Ptolemy Philopator “Loving His Father” Under his feeble rule, heavily influenced by favorites, much of Ptolemaic Syria was lost and native uprisings began to disturb the internal stability of Egypt.

Classical writers depict Ptolemy as a drunken, debauched reveler, completely under the influence of his disreputable associates, among whom Sosibius was the most prominent. At their instigation, Ptolemy arranged the murder of his mother, uncle, and brother.

Following the defection of one of Ptolemy’s best commanders, Egypt’s Syro-Palestinian territory, Coele Syria, was seriously threatened by Antiochus III, the Syrian Seleucid ruler. In 219, when the Seleucid ruler captured some of the coastal cities, Sosibius and the Ptolemaic court entered into delaying negotiations with the enemy, while the Ptolemaic army was reorganized and intensively drilled. So grave was the threat that for the first time under the Ptolemaic regime native Egyptians were enrolled into the infantry and cavalry and trained in phalanx tactics. In 218 the negotiations collapsed, and Antiochus renewed his advance, overrunning Ptolemy’s forward defenses. In the spring of 217, however, Ptolemy’s new army met the Seleucid forces near Raphia in southern Palestine, and with the help of the Egyptian phalanx Ptolemy was victorious. Although holding the initiative, the Egyptian king, on Sosibius’ advice, negotiated a peace, and the Seleucid army withdrew from Coele Syria.

After Raphia, Ptolemy married his sister, Arsinoe, who bore him a successor in 210 BC. The Egyptians, however, sensing their power, rose in a rebellion that Polybius, the Greek historian describes as guerrilla warfare. By 205 BC the revolt had spread to Upper Egypt.

To the south, Ptolemy maintained peaceful relations with the neighboring kingdom. In the Aegean, he retained a number of islands, but, in spite of honors granted him, he refused to become embroiled in the wars of the Greek states. In Syria, also, Ptolemy avoided involvement in local struggles, though Sosibius attempted to embroil Egypt there. According to Polybius, Ptolemy’s debauched and corrupt character, rather than his diplomatic acumen, kept him clear of foreign involvements. As his reign progressed he fell increasingly under the influence of his favorites, and around November 205 he died. His clique of favorites kept Ptolemy’s death a secret, and about a year later murdered Queen Arsinoe, leaving the young successor at their mercy.

Ptolemy V

Ptolemy V (210-181 BC) was known as Ptolemy Epiphanes (“illustrious”) and was king of Egypt from 205-181 BC. He was the grandson of Ptolemy III Euergetes. At the beginning of his reign, Antiochus III of Syria and Philip V of Macedonia agreed to divide the foreign possessions of Egypt between them, and Egypt was greatly weakened. The official coronation of Ptolemy V was held in 197 BC; it was the occasion on which the Egyptian priesthood published the decree that forms the trilingual inscription on the Rosetta Stone. In 193 BC Ptolemy married the Seleucid princess Cleopatra I.

Ptolemy VI

Ptolemy VI (186-145 BC) was also known as Ptolemy Philometor (“loving his mother”). He was king of Egypt from 181-145 BC, and was the son of Ptolemy V and Cleopatra I.

The son of Ptolemy V Epiphanes and Cleopatra I, Ptolemy VI ruled as co-regent with his mother, who, although a daughter of a Seleucid king, did not take sides with Syria and remained friendly with Rome. Mother and son governed effectively until her death in 176, when Ptolemy fell under the influence of two ambitious courtiers. Around 173 Ptolemy was married to his sister, Cleopatra II. Under his advisers’ guidance, preparations were made to invade Coele Syria. In 170 Ptolemy VIII Euergetes, his brother, was associated on the throne with Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II, and Coele Syria was invaded, but the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV decisively defeated the Egyptians and seized Pelusium, the Egyptian frontier city. Antiochus invaded Egypt in 170 and again in 168, but withdrew under pressure from the Ptolemies’ ally, Rome. About October 164 Philometor was expelled from Alexandria by his brother and fled to Rome for support. The Romans thereupon partitioned the Ptolemaic realm, ordering Euergetes into Cyrenaica and giving Philometor Cyprus and Egypt.

Euergetes, not content with Cyrenaica alone, journeyed to Rome twice to ask for Cyprus also. The Senate finally decided to grant the brother’s request; Philometor, however, delayed the Romans by clever diplomacy and in 154 defeated his brother, who attempted to seize Cyprus by force. Nevertheless Philometor restored his brother to Cyrenaica, married a daughter to him, and granted him a grain subsidy. In Rome, meanwhile, the Roman statesman Cato the Elder, deploring the continuous intrigues, praised Ptolemy VI as a good and beneficent ruler. At last Philometor’s kingdom became relatively secure.

In 155, however, the Seleucid ruler of Syria had incurred Ptolemy’s enmity by conspiring to seize Cyprus. When a pretender, Alexander Balas, appeared, Philometor hastened to aid him in 153, and later even gave him a daughter in marriage. About 148, however, the Egyptian king found himself in Syria again when another pretender appeared. When Alexander Balas failed in his attempt to have Philometor assassinated, the Egyptian ruler bestowed his daughter, Balas’ wife, on the new pretender. Although Ptolemy supported him, the people of Antioch and the Syrian army asked the Egyptian monarch himself to become their ruler. Ptolemy declined, but he was soon drawn into a battle in which Alexander Balas was defeated and slain. During the battle Ptolemy fell from his horse and fractured his skull, dying a few days later.

Ptolemy VII

Not much is known about Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator (“Ptolemy the New Beloved of his Father”). It is thought by some that he reigned briefly with his father, Ptolemy VI, c. 145 BC, and was probably murdered by his uncle, Ptolemy VIII.

Ptolemy VIII

Ptolemy VIII (184-116 BC) was known as Ptolemy Euergetes (“benefactor”) II and was the king of Egypt from 145-116 BC. He was the son of Ptolemy V and the brother of Ptolemy VI. He was portrayed by Greek writers as a cruel despot, but according to Egyptian sources he was responsible for administrative reforms and the liberal endowment of religious institutions.

The Ptolemaic Empire became permanently disunited after his death. His will bequeathed Cyrenaica to his illegitimate son Ptolemy Apion and Egypt and Cyprus to his second wife Cleopatra III, who was instructed to choose one of her sons as a joint ruler.

Ptolemy IX

The unusual will of Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II partitioned Egypt’s possessions, leaving his widow Cleopatra III as the effective ruler of Egypt and Cyprus. Although she preferred his younger brother, Ptolemy X Alexander I, popular sentiment forced the dowager queen to dismiss him and to associate Ptolemy IX Soter II on the throne with herself. After compelling the king in 115 to divorce his strong-willed sister-queen, Cleopatra IV, his mother forced Ptolemy to marry his younger, more pliable sister, Cleopatra Selene. The next year, after his brother was sent to Cyprus as governor, Ptolemy IX Soter II appeared with his mother as joint ruler of Egypt. The latent hostility between the son and his mother finally erupted in October 110, when Cleopatra III expelled him from Egypt and recalled his brother Potelemy X Alexander I from Cyprus. Soter II returned in early 109 but was evicted anew by his mother in March of the following year.

After reconciliation in May 108 Ptolemy IX Soter II fled a third time and established himself in Cyprus, from where in 107 he invaded northern Syria to assist one of the claimants to the Seleucid empire, while his mother, allying herself with the Jewish king in Palestine, actively aided another Seleucid pretender. During the protracted war his mother died (101) and Ptolemy X Alexander became the sole ruler of Egypt, while Soter II remained entrenched in Cyprus.

After Ptolemy X Alexander I’s unpopularity drove him from Alexandria a second time and he perished at sea, Ptolemy IX Soter II returned to resume sole rule over Egypt. Lacking a queen, he brought back his brother’s widow, who was also his own daughter, Berenice III, and associated her on the throne with himself. Shortly before Soter’s II return in 88 a serious native rebellion erupted around Thebes in Upper Egypt. After three years of hard fighting Thebes capitulated and was sacked in retribution.

Ptolemy IX Soter II refused to give aid to the Romans in the course of their war with Pontus, a Black Sea kingdom, and after the Roman sack of Athens in 88 the Egyptian rulers helped rebuild the city, for which commemorative statues of them were erected. Ptolemy IX died in 81, leaving his daughter and widow as his successor.

Ptolemy X

Ptolemy X was known as Alexander I of Egypt. He reigned from 107-88 BC. Under the direction of his mother, Cleopatra III, he ruled Egypt alternately with his brother Ptolemy IX Soter II and around 105 became involved in a civil war in the Seleucid kingdom in Syria.

Son of Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II, Ptolemy Alexander was sent to Cyprus as governor in 114 BC after the opposition of the people of Alexandria prevented his mother from securing the kingship of Egypt for him. When, at the instigation of the queen mother, his elder brother, Ptolemy Soter, was expelled from Egypt in 110, Ptolemy Alexander was recalled from Cyprus and replaced him as coregent in Egypt. Following a reconciliation in early 109, Soter returned and occupied the throne, while Ptolemy Alexander departed for Cyprus as king of the island. Another bitter quarrel between his brother and mother brought Ptolemy Alexander back to Egypt as coregent in 107, but Cleopatra III took official precedence and was the actual ruler.

While the queen mother continued to pursue the family dispute, Ptolemy Alexander found himself drawn into a civil war in the Seleucid kingdom, after his brother lent active aid to the opponents of his mother’s allies. With the queen’s death in 101 the war ended, and Ptolemy Alexander was reconciled with his brother and even married Soter’s daughter, Berenice III.

In 89 the army in Alexandria turned against Ptolemy Alexander, and he was forced into exile. After gathering a mercenary force in Syria-Palestine, the king returned the following year, but when he plundered the temple-tomb of Alexander the Great in Alexandria to pay his troops, the infuriated populace of the city expelled him again, and he was killed at sea between Lycia in Asia Minor and Cyprus. His widow, who had accompanied him into exile, subsequently returned to Egypt to become his brother Soter’s queen.

Ptolemy Alexander extended the rights of Egyptian natives, who pressed for further extensions. In 88, the year of his death, a rebellion erupted in the region of Thebes in Upper Egypt with the aim of establishing a native dynasty; this was finally suppressed under his predecessor and successor, Ptolemy IX. During the uncertain years that followed, the Seleucid Empire in Syria collapsed and the Nabataeans became the major rulers in the Middle East. Given the long history of peaceful co-existence between the Nabataeans and the Ptolemies by this time, the Ptolemaic Dynasty was saved from invasion from the east.

Ptolemy XI

Ptolemy XI Alexander II was the son of Ptolemy X Alexander I, probably by his wife Cleopatra Selene.

After the death of Ptolemy IX, his widow Berenice III ruled over Egypt for a short period, before being married to Ptolemy XI Alexander II, likely forced into it by Roman interference.

The marriage was extremely short, thought to be only a few weeks in length, ending with the new ruler Ptolemy XI murdering Berenice III.

In retaliation of the murder, Ptolemy XI was in turn killed by his own citizens shortly after.

Ptolemy XII

Ptolemy XII was known as Theos Philophater Philadelphus. He was also known as Neos Dionysos or Auletes the Flute Player He was the illegitimate son of Lathyros (Ptolemy IX Soter II). His younger brother became governor of Cyprus and Ptolemy XII came to Alexandria to rule after the death of Ptolemy XI Alexander II. He was often referred to by his subjects as the Bastard or the Flute Player (Auletes). He referred to himself as ‘Theos Philopator Philadelphos Neos Dionysos’. It is only in the history books that he is referred to as Ptolemy XII. He was married to his sister-wife, Cleopatra V Tryphaena and was the father of the famous Cleopatra VII, who grew up to be the last of the Ptolemies. During his reign Egypt became virtually a client kingdom of the Roman republic.

Following the sudden, violent deaths of Berinice III and Ptolemy XI, the last two fully legitimate members of the Ptolemaic family in Egypt, the people of Alexandria in 80 invited Ptolemy XII to assume the throne. Although he was known as a son of Ptolemy IX Soter II, the identity of his mother is not certain. In 103 he was sent by his grandmother, Cleopatra III, queen of Egypt, in the company of his brother and Ptolemy XI Alexander II, his predecessor, to Cos, an Aegean island near Asia Minor, for safekeeping. Captured in 88 by Mithradates VI Eupator, ruler of Pontus, a kingdom in Asia Minor that was then at war with Rome, young Ptolemy appeared in 80 in Syria, from where, according to the Roman historian and politician Cicero, he arrived in Egypt, while his brother became king of Cyprus.

Shortly after his arrival in Egypt Ptolemy married Cleopatra V Tryphaeana, perhaps his sister, and in 76 he was crowned in Alexandria according to Egyptian rites. At Rome, however, the democratic faction in 65 raised the issue of Ptolemy’s legitimacy, producing a questionable will of Ptolemy XI Alexander II purporting to bequeath Egypt to the Roman people. The aristocracy at Rome, including Cicero, opposed the annexation, while Ptolemy, seeking Roman support, sent troops to assist the consul and general Pompey the Great in Palestine. Facing serious opposition from the people of Alexandria and still unsure of his status at Rome, he bribed Julius Caesar, one of the Roman consuls for the year 59, with 6,000 talents, in return for which Caesar passed a law acknowledging his kingship. Rome nevertheless divested Egypt of Cyprus the next year, and, when his brother in Egypt failed to support him, the island’s king committed suicide.

Fearing popular insurrection over the loss of Cyprus, Ptolemy in 58 went to Rome to seek military aid and left his queen and his eldest daughter, Berenice IV, as regents in Egypt. Residing at Pompey’s villa at Rome, he employed bribery to obtain the support of the Roman senators. He also arranged the assassination of delegations sent by his opponents from Alexandria, where, following his queen’s death, the people had made Berenice IV sole ruler. While the Senate delayed an answer, Ptolemy, continuing to dispense bribes, fell deeper into debt to Roman moneylenders. Late in 57 the Senate passed a resolution to support Ptolemy, but, when a prophecy forbade the granting of active aid, the Egyptian king departed for Ephesus, a city in Asia Minor.

In 55, after promising Pompey’s lieutenant Aulus Gabinius, proconsul of Syria, 10,000 talents, Ptolemy was returned to Egypt with a Roman army. Once restored, he executed his daughter, who had headed the opposition at Alexandria. Shortly before his death in 51 he proclaimed his eldest surviving daughter, the celebrated Cleopatra VII, and his eldest son coregents.

Ptolemy XIII

Ptolemy XIII was known as Theos Philophator, or God Loving His Father. He ruled from 55 BC until 47 BC, He was co-ruler with his famous sister, Cleopatra VII. He was killed while leading the Ptolemaic army against Julius Caesar’s forces in the final stages of the Alexandrian War.

A son of Ptolemy XII Auletes, Ptolemy XIII became joint ruler of Egypt with his sister following his father’s death. In 49 Ptolemy, seeking to retain his father’s allies, supplied the Roman general and former triumvir Pompey the Great with ships and troops. Subsequently a court clique, headed by Theodotus, the eunuch Pothinus, and the general Achillas, gained influence over the King, fanning the growing rivalry between him and his strong-willed sister. Expelled from Egypt by the King and his clique in 48, she quickly raised an Arab army and besieged Pelusium, a city on the northeast frontier of Egypt. As the opposing forces prepared for war, Pompey, decisively defeated by Caesar at Pharsalus in Thessaly, and appeared at Pelusium seeking refuge. He was murdered however, on orders of the palace clique, which sought to gain favour with Caesar.

Shortly afterward, Caesar arrived at Alexandria and, seizing the palace quarter, ordered the warring factions to submit to his arbitration as authorized by the will of Ptolemy’s father. Leaving General Achillas with the army, Ptolemy went with Pothinus to Caesar’s camp, while Cleopatra arrived in the palace, reportedly concealed in a carpet. With all the members of the Ptolemaic royal family in his grasp, Caesar effected a reconciliation between Ptolemy and his sister.

Pothinus’ group, however, continued to foment trouble against the Romans and their Egyptian allies; and after Achillas brought up the army to besiege Alexandria, Ptolemy’s youngest sister, Arsinoe, escaped to the native forces. Caesar, meanwhile persuaded Cleopatra to execute Pothinus, while Achillas was killed after feuding with Arsinoe, thus effectively destroying the clique. Pressed hard by the native forces under Arsinoe and her tutor, Caesar negotiated an exchange of Ptolemy for Arsinoe. The King immediately took command of the Egyptians; but Caesar, reinforced by an army from Pergamum, a city in Asia Minor, out maneuvered the Ptolemaic forces; and the King was killed, probably by drowning as he attempted to flee.

Cleopatra VII

Cleopatra (69-30 BC) was the last member of the Ptolemaic dynasty to rule Egypt (51-30 BC), and is celebrated for her love affairs with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. Cleopatra VII was the daughter of Ptolemy XII Auletes, king of Egypt. On her father’s death in 51 BC Cleopatra, then about 17 years old, and her brother, Ptolemy XIII, a child of about 12 years, succeeded jointly to the throne of Egypt on condition that they marry. In the third year of their reign Ptolemy, encouraged by his advisers, assumed sole control of the government, and drove Cleopatra into exile.

She promptly gathered an army in Syria but was unable to assert her claim until the arrival at Alexandria of Julius Caesar, who became her lover and espoused her cause. He was for a time hard pressed by the Egyptians but ultimately triumphed, and in 47 BC Ptolemy XII was killed. Caesar proclaimed Cleopatra queen of Egypt. Cleopatra was then forced by custom to marry her younger brother, Ptolemy XIV, then about 11 years old. After putting their joint government on a secure basis, Cleopatra went to Rome, where she lived as Caesar’s mistress. She gave birth to a son, Caesarion, later Ptolemy XV, whom Marcus Antonius confirmed had been acknowledged by Caesar as his son. After his assassination in 44 BC, Cleopatra returned to Egypt and Ptolemy XIV disappears, she then made Caesarion her co-regent.. She put her strategos on Cyprus to death for supporting Cassius in the civil war following Caesar’s death and in 41 BC. She was summoned to Tarsus (in modern Turkey) by Mark Antony to ensure her loyalty. He fell in love with her and returned with her to Alexandria where they lived together for some time. In 40 BC Antony was compelled to return to Rome, where he married Octavia, a sister of Octavian, later the Roman emperor Augustus. After Antony’s departure Cleopatra gave birth to twins.

In 36 BC Mark Anthony gave Cleopatra several coastal cities in Syria, Lebanon and Judea along with the bitumen mines near the Dead Sea which belonged to the Nabateans, who consequently felt great enmity against her. Then Antony went to the East as commander of an expedition against the Parthians. He sent for Cleopatra, who joined him at Antioch. They were married, and a third child was born. In 34 BC, after a successful campaign against the Parthians, he celebrated his triumph at Alexandria and he and Cleopatra formally announced the division of the former empire of Alexander the Great between Cleopatra and her children. Antony continued to reside in Egypt and in 32 BC Octavian declared war against the couple and Antony divorced Octavia.

Cleopatra insisted on taking part in the campaign. At the naval battle of Actium in 31 BC, believing Antony’s defeat to be inevitable, she withdrew her fleet from action, and she and Antony fled to Alexandria. Soon after, the two of them had sixty ships dragged across the Suez isthmus from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. They then started outfitting these ships in order to make their escape to legendary India. The Nabataeans however saw their opportunity to take revenge on Cleopatra for taking the bitumen mines and immediately moved to destroy it. Upon hearing that their fleet was destroyed the two were thrown into despair.

Soon after this Antony was deceived by a false report of Cleopatra’s death and committed suicide. On hearing that Octavian intended to exhibit her in his triumph at Rome, The official Roman version is that Cleopatra also killed herself, probably by poison, or, according to an old tradition, by the bite of an asp. Caesarion, the last of the Ptolemies, was put to death by Octavian, and Egypt passed into Roman hands. *

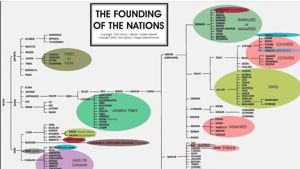

Ptolemaic Influences on the Nabataean Civilization

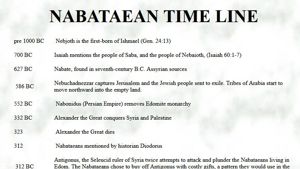

In 85 BC the Nabataeans marched into the ancient city of Damascus and suddenly became a world power. Every since the first Ptolemy ruled from Egypt they had been shipping their goods through the Egyptian port of Alexandria. Now with a world class city of their own, the Nabataeans suddenly embraced Hellenization wholeheartedly. The sweeping reforms that would change their kingdom forever were, for the most part, based on their admiration for the rulers of Alexandria.

One of the first acts of Aretas III (86 - 62 BC), the new king of Damascus, was to being to mint new coins, with his Greek name, Philhellene displayed for all to see. However, Aretas not only displayed his new Greek name and title in the Greek language, he also displayed his wife alongside of him, in typical Polemic fashion.

Photo showing king and queen coin images, King Aretas IV

Along with this, Nabataean rulers seemed to follow the Egyptian tradition of instituting brother/sister marriages. During the reign of Aretas IV, the queens of his reign were Huldu and Shuqailat. They were referred to as his sisters, although historians have argued whether the term ‘sister’ meant that these two were his actual sisters, or whether the term ‘sister,’ simply referred to them as female. Brother-sister marriages were not unknown at that time. Ptolemy II Philadelphus married his sister Arsinoe in 277 BC and afterwards this became the standard practice in the Royal House in Alexandria. This custom was an old tradition in Pharaonic Egypt and existed even later among the Seleucid dynasties of Syria. It would seem that the Nabataean rulers also followed suite in practicing this form of marriage.

Added to this, the Nabataean architectural style matured during this time, but it borrowed heavily on the Alexandrian style. Not only do the tombs in Petra depict Alexandrian style, but also the massive architectural projects that the Nabataeans undertook are reminiscent of massive architectural undertakings in Alexandria.

During the lifetime of Ptolemy I Soter, he was proclaimed a deity or god by various classes of people. Upon his death the Egyptian people raised him to a level of a god. This is paralleled in Nabataean history, when the Nabataean king Obodas I was deified and worshiped as a god. This is attested by an inscription that was found near the Deir monument in Petra.

Nabataean tombs and burial methods also find parallels in Egypt and among the tombs of the Ptolemies. The Nabataeans were quick to follow the Egyptian practice of building impressive tombs for their honored leaders.

The Nabataeans not only copied their Egyptian neighbors in religious and funerary practices, they also copied them in life. Egyptian and Greek names were given to their children, and Egyptian and Greek style dress became popular in Nabataea.

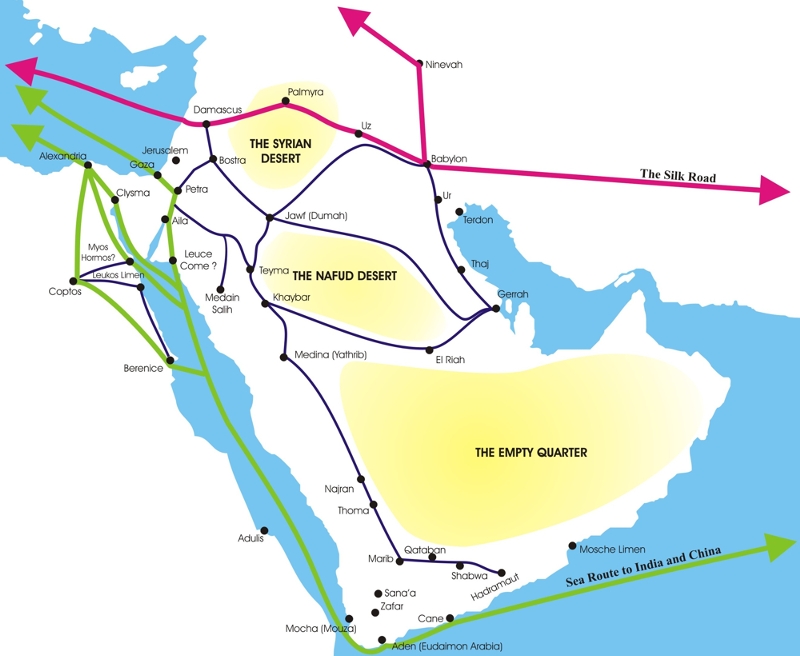

If the Nabataeans were the principle merchants of Alexandria, then it was Nabataean trade that made Alexandria rich. The map below demonstrates the merging of trade routes in Alexandria.

The Nabataeans were also involved in the creating and collecting of knowledge. Their input into the Great Library in Alexandria as well as the Museum with its investigations into geography, mathematics, astronomy and other sciences would have been of great interest to the Nabataean scholars. Arab literature (from later dates) mentions many Nabataean contributions to science and culture. Abu Bakr Ahmad ibn Ali ibn Qais ibn Wahsiyah an-Nabati, who was a physician and botanist with interests in agriculture, animal husbandry as well as alchemy, magic and toxicology, wrote around 900 AD. He was not only a scholar of his day, but perhaps the greatest spokesperson on behalf of his illustrious ancestors, the Nabataeans, to whom he attributed nine-tenths of all scientific knowledge known. His books are known as Al-Filiaheh an-Nabatiyah (904 AD) and As-Sumum wat-Tiyaqat (900 AD). Even if his suggestions are overstated, it does reflect the Nabataean’s quest for the accumulation of knowledge. Some historians have suggested that the early Ptolemies may have elicited the help of Nabataean merchants and sailors in their quest for knowledge from distant shores. The Nabataeans, in obtaining and transmitting this knowledge to the scholars in Alexandria would have become the Arab source for this knowledge. The fact that many books from the library in Alexandria were later translated into Arabic, the language of the Nabataeans, is another indicator of the role that the Nabataeans must have played.

From history we can deduce that many Nabataeans were present in Alexandria in Egypt. They left evidence of their presence not only in this city, but in many of the centers around the Mediterranean Sea. From the many Hellenistic and Alexandrian influences in Nabataean culture we can conclude that no other civilization influenced the Nabataeans in as many ways and to such a depth as the Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt.

- With thanks to Rose Moloney Ph D; DD, (and guest speaker on Jordan, Fred Olsen Cruise Line) for her work on the Cleopatra VII section, based on Plutarch’s Life of Marcus Antonius. She notes that the disappearance of Ptolemy IV was assumed to be her doing by her enemy Nikolaus of Damascus, the source for Josephus’ antagonistic account. This was unfounded.

Bibliography

Bevan, Edwyn. The House of Ptolemy. Argonaut Inc. Chicago: 1968

Bolling, G. M. Alexandria, Transcribed by Thomas J. Bress, A History of Classical Scholarship (Cambridge, 1903); Real-Encyclopædie, III, 409-414

Cairo P., Zennon Papyri 59021. cf. Cl. Preaux, Économie Royale des Lagides, 271, n.2

Canfora, Luciano. The Vanished Library. trans. Martin Ryle. University of California Press. Berkely: 1989

Cary, Max, A History of the Greek World from 323 to 146 B.C., 2nd ed. rev. (1951)

Casson, L., editor, The Periplus Maris Erythraei, Princeton 1989

El-Abbadi, M., ‘Cleomenes’, Bull. Faculty of Arts, Alexandria 17 (1964) 65-85 (in Arabic)

Edgar, C., Annales des Services. 22 (1922)

Ellis, Ptolemy of Egypt. Routledge. New York: 1994

Fraser, P. M. Ptolemaic Alexandria. Volume I of III. Oxford University Press. Oxford: 1972

Gibson, Dan, The Nabataeans, Builders of Petra, CanBooks, Booksurge, 2003

Heinen, H., Untersuchungen zur hellenistischen Geschichte des 3. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. (1972)

Johnson, Emer D. History of Libraries in the Western World. Scarecrow Press, Inc. Metuchen: 1970

Longega, G., Arsinoe II (1968; in Italian)

MacAdam, H., ‘Strabo, Pliny and Ptolemy of Alexandria’, in: Arabie Pre-Islamique (Strasbourg 1989)

Marlowe, John. The Golden Age of Alexandria. Trinity Press. London: 1971

Microsoft® Encarta® 99 Encyclopedia. © 1993-1998, “Ptolemaic Dynasty,“

Otto W. & H. Bengtson, Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches, München 1938

Roccati, A., Nuove epigrafi grechi e latine da file, Homage Vermaseren III., pp. 988-96, Année Épigraphique (1977) 838-9; and Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum, 28, no. 1485

Roussel, P., _Delos Colonie Athenienne (_Paris 1916), pp. 92-3

Sammelbuch, 8036, _Coptos, I_nscriptions Philae, 52 (62 BC)

Seibert, Jakob Untersuchungen zur Geschichte Ptolemaios’ I. (1969)

Tarn, W.W. The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 6, ch. 15, and vol. 7, ch. 3 (1927-28)

Thiel, J. Eudoxus of Cyzucus, Groningen 1966

Walbank, F. W., Hellenistic World, Harvard U. Press (1981)

Will, E., Histoire politique du monde hellénistique (323-30 av. J.-C.), vol. 1 (1966)

van’t Dack, E., ‘Les relations entre l’Égypte Ptolemaïque et l’Italie’, Egypt and the Hellenistic World, Studia Hellenistica 27 (Louvain 1983) 383-406

Volkmann, H., Ptolemaios II. Philadelphos, in Pauly-Wissowa Realencyclopädie, vol. 46, col. 1645-1666 (1959)

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!