Introduction

The origin of the Arabian horse remains a zoological mystery. Although this unique breed has had a distinctive national identity for centuries, its history nevertheless is full of subtleties, complexities, and contradictions. During my study of the Nabataeans, however, I have wondered if there was some connection between this mysterious people and this elusive breed of horses.

When we first encounter the Arabian horse, or the prototype of what is known today as the Arabian, he is somewhat smaller than his counterpart today. Otherwise he has essentially remained unchanged throughout the centuries

Authorities are at odds about where the Arabian horse originated. The subject is hazardous, for the archaeologist’s spade and the shifting sands of time are constantly unsettling previously established thinking. There are certain arguments for the ancestral Arabian having been a wild horse in northern Syria, southern Turkey and possibly farther east in Mesopotamia. The area along the northern edge of the Fertile Crescent comprising part of Iraq and running along the Euphrates and west across Sinai and along the coast to Egypt, offered a mild climate and enough rain to provide an ideal environment for horses. Other historians suggest this unique breed originated in the southwestern part of Arabia. They suggest that the three great river beds in this area provided a natural wild pasture and were obviously the centers in which the Arabian horse first appeared as an undomesticated creature.

Because the interior of the Arabian peninsula has been dry for approximately 10,000 years, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, for horses to exist in that arid land without the aid of man. The domestication of the camel in about 3500 B.C. provided the Bedouins with a means of transport and sustenance. It is thought that as the Bedouins moved into central Arabia around 2500 B.C, that they took with them the prototype of the modern Arabian horse.

Many equestrian historians today claim that while the Arabian horse is an original breed, the modern horses that we have today were, in their opinions, obviously bred by someone, somewhere in their history.

Ancient Middle Eastern history does not tell us in which country the Arabian horse was first domesticated, or whether they were first used for work or riding. Historians assume that they were probably used for both purposes in very early times and in various parts of the world. We do know, however that by 1500 B.C. the people of the east had obtained great mastery over their hot-blooded horses which were the forerunners of the modern breed which eventually became known as “Arabian.”

About 3500 years ago the horse brought tremendous changes in the east, including the valley of the Nile and beyond, changing human history and the face of the world. For instance, once they obtained horses, the Egyptians became aware of the vast world beyond their own borders. The Pharaohs were able to extend the Egyptian empire by harnessing the horse to their chariots. Likewise, the empires of the Hurrians, Hittites, Kassites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians and others rose and fell under the thundering hooves of early horses.

Early depictions of the horse appear on seal rings, stone pillars and various monuments with regularity after the 16th century B.C. Egyptian hieroglyphics proclaimed the horses’ value; Old Testament writings are filled with references to the horses’ might and strength. King Solomon (around 900 years B.C.) eulogized the beauty of “a company of horses in Pharaoh’s chariots,” and later 490 B.C. the famous Greek horseman, Xinophon proclaimed that the horse was “a noble animal which exhibits itself in all its beauty, and is something so lovely and wonderful that it fascinates young and old alike.”

Origin of the Arabian Breed

“And God took a handful of South wind and from it formed a horse, saying: “I create thee, Oh Arabian. To thy forelock, I bind Victory in battle. On thy back, I set a rich spoil And a Treasure in thy loins. I establish thee as one of the Glories of the Earth… I give thee flight without wings.” – from an Ancient Bedouin Legend (Byford, et al. Origination of the Arabian Breed)

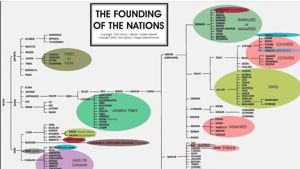

The origin of the word “Arab” is still obscure. A popular concept links the word with nomadism, connecting it with the Hebrew “Arabha,” dark land or steppe land, also with the Hebrew “Erebh,” mixed and hence organized as opposed to organized and ordered life of the sedentary communities, or with the root “Abhar”-to move or pass. “Arab” is a Semitic word meaning “desert” or the inhabitant thereof, with no reference to nationality. In the Koran a’rab is used for Bedouins (nomadic desert dwellers) and the first certain instance of its Biblical use as a proper name occurs in Jeremiah 25:24: “Kings of Arabia,” Jeremiah having lived between 626 and 586 B.C. Roman historians referred to the Nabataeans as Arabs and the Arabs as Nabataeans. The Arabs themselves seem to have used the word at an early date to distinguish the Bedouin from the Arabic-speaking town dwellers.

With the rise of Islam Muslims from Arabia flooded out into the rest of the Middle East. These Arabs rode the famous Arabian horse and they used this horse as the main element of their armed forces as they smashed their way through their opposition, overrunning the southern half of the Byzantine empire, the entirety of the Persian Sassanid Empire, then drove their armies through North Africa, across the Mediterranean into Iberia, and then deep into Europe. The prophet Mohammed was instrumental in spreading the Arabian’s influence among the Arabs. He mandated that the Arabians’ numbers be increased, as the horses would be crucial to the inevitable battles that would be required for his religious conquests. He also proclaimed that Allah had created the Arabian, and that those who treated the horse well would be rewarded in the afterlife. These incentives, coupled with the Koran’s instruction that “no evil spirit will dare to enter a tent where there is a purebred horse,” further spurred the breeding of the Arabian.

The Bedouin horse breeders were fanatic about keeping the blood of their desert steeds absolutely pure, and through line-breeding and inbreeding, celebrated strains evolved which were particularly prized for distinguishing characteristics and qualities. The mare evolved as the Bedouin’s most treasured possession. The harsh desert environment ensured that only the strongest and keenest horse survived, and it was responsible for many of the physical characteristics distinguishing the breed to this day.

Historical figures like Genghis Khan, Napoleon, Alexander the Great and George Washington rode Arabians. Even today, one finds descendants from the earliest Arabian horses of antiquity. Then, a man’s wealth was measured in his holdings of these fine animals. Given that the Arabian was the original source of quality and speed, and remains foremost in the fields of endurance and soundness, he still either directly or indirectly contributed to the formation of virtually all the modern breeds of horses.

The Middle East and the Arabian Horse

By the time the Roman Empire overran Nabataea, the horse had become the transport animal of choice. Oxen and donkeys were still used by local farmers and merchants, but the use of horses had usurped every other transport animal. Horses were used to pull carriages, chariots, and wagons. Horses were also used for individual riders. Horses were used in the army for mounted cavalry units and mounted archers and horses were used in the circus for entertaining, and even in the dangerous sport of chariot racing.

Around 100 BC horses in Arabia started overtaking the camel in popularity, the later being relegated to being a simple pack animal while wealth was suddenly equated with the number of horses one owned.

The Roman View of Horses

Today we posses considerable knowledge about horses during the Roman times, due in particular to the works of poets such as Virgil, Oppian, Nemesian and Gratius Faliscus, the geographer Strabo; the gentleman farmers Varro and Columella; and to the unknown traveler writing to his son in the work known to us as the Expositio Totius Mundi et Gentium. Pliny the Elder also throws a little light on the areas concerning horse breeding and later on his nephew describes the facilities owned by gentlemen riders as well as the string of ponies owned by a fortunate child.

In Roman literature we can discover three main categories of horses: the warhorse of Virgil, the hunting horses of Nemesian, Oppian and Gratius Faliscus, and the racehorses of Pelagonius.

Columella and Pelagonius provide us with a description of what the ideals were in a horse:

Small head, black eyes, nostrils open, wars short and picked up; neck flexible and broad without being long; mane thick and falling on the right side, broad and muscular chest, big straight shoulders, muscles sticking out all over the body, sides sloping in, double black, small belly, stones small and alike, flanks broad and drawn in, tail long and not bristly, for this is ugly; legs straight; knee round and small, and not turned in, buttocks and thighs full and muscular; hoofs black high and hollow, topping off with moderate sized coronets. He should in general be so formed as to be large, high, well set up, of an active look, and round-barreled in the proportion proper to his length.(Pelagonius, Ars Vet., quotes in Morgan 1962, page 115)

This is generally a description that today’s horseman would agree with, especially for a horse that would be used for rigorous hard and stressful work. However, to obtain a horse like this, breeding must have taken place.

There is ample evidence, as we will discover later, that breeding centers for horses were set up all over Europe and North Africa, and even in the Middle East. Horses that showed positive traits were cross bred to provide offspring with these traits. Eventually, with successive breeding, powerful and distinctive breeds of horses were developed in various parts of the Roman world.

The list below explains the things that were desired in a horse.

- Small head. Heavy-headed horses nearly always have poorly proportioned bodies, which put the horse under a lot of strain when doing heavy work.

- Clear eyes. In ancient days, black eyes were preferred and today many breeders still prefer black eyes, however there is now no clinical proof that black eyes are any better than other colored eyes. The clearness of the eye is more important, and any cloudiness or spotting in the eye indicates trouble.

- Open nostrils, or nostrils capable of extreme dilation. This is vital for an adequate intake of air, especially on a hard worked horse in hot weather. Battle chargers used by Roman cavalry on long campaigns had to endure long marches and be prepared to take action when they arrived at their destination. A horse that could not regulate its heat build-up would ‘tie-up’ and collapse.

Another important aspect that the Roman army desired in their horses as a lack of intelligence. They preferred great strong horses that would not think for themselves but would blindly follow their masters into dangerous situations. Thus, the Roman cavalry was made up of great brutes of horses that charged into almost certain death with little fear.

Unfortunately, the Arabian horse did not fit this requirement, as it was a very intelligent horse, capable of thinking for itself. It was highly prized by the Arabs, for its ability to survive in the desert, and was perfectly suited to individuals and small groups. As a result, the Arabian horse was not bred in the stables of Europe, but was relegated to the breeding activities of marginalized peoples in Arabia.

The Nabataeans

During the reign of Aretas III, Damascus was captured, and the Nabataeans entered into Hellenization with real gusto. One of the results of this Hellenization was adoption of the horse as an honorable means of transport. Camels continued to be pack animals, but horses were desired by those wishing to ride in style. The famous Nabataean camel cavalry was soon replaced by horse riding Nabataeans.

The Nabataean cavalry was traditionally camel mounted; usually with two archers, one facing forward and one facing either front or back as illustrated left.

By 47 BC, Nabataean ruler Malichus I honored a request from Julius Caesar and provided him with 2000 horse cavalry during the Roman dictator’s Alexandrian campaign.

According to Josephus, Malichus II sent Emperor Titus 1000 cavalry and 5000 infantry in 70 AD, which took part in the destruction of Jerusalem.

Following this, during the reign of Rabbel II, emphasis was placed on developing the agricultural resources of the Nabataean Empire. Horse breeding was stepped up, and soon stables and horse ranches dotted the Nabataean countryside. These Arabian bred horses were sold to wealthy individuals within the Roman empire, as well as to Roman circuses where they performed and raced to the delight of the Roman populace.

The statue of the Nabataean cavalry man in the side of the wall in Kerak Castle. The castle is crusader, but some of the blocks on the lower lever were taken from older structures on the same location. The relief of the Nabataean cavalry man shows a man with ribbons tied in his long curly hair, a spear over one shoulder, and a horses head over the other shoulder.

Archeological evidence has now surfaced in Safaitic texts that provide evidence of extensive horse-breeding through out the Nabataean empire, especially in the Hauran region. At present there is not a great deal of proof about what type of horses the Nabataeans bred, but by carefully analyzing the historical records we can learn some of the characteristics of these horses.

Nabataean horses were known to be swift, light, and very intelligent. The Romans preferred horses that could carry heavily armored and armed men into battle, and that were not terribly bright. This gave them the edge, as often their horses did not sense danger until it hit them. The Nabataeans on the other hand preferred fast horses that could, in the words of Diodorus “… flee into the desert, using this as a stronghold.” These horses sound much like the famed Arabian breed of horses.

Compared to European horses, Arabian horses were small but were fast and had remarkable powers of endurance. They were also prized for their beauty, intelligence, and gentleness. Arabian horses usually have only 23 vertebrae while the European horses have 24. Their average height was about 15 hands (60 inches, or 152 cm), and their average weight ranged from 800 to 1,000 pounds (360 to 450 kg). They were also noted for having strong legs and fine hooves. Their coat, tail, and mane were of fine, silky hair. Although many colors are possible in the breed, gray prevails.

Roman historians tell us that after 106 AD, when the Romans annexed the Nabataean Empire, that Nabataean cavalry units proved to be undisciplined and a poor accompaniment for the well structured, disciplined Roman army. At this point, it seems that the Arabian horse disappears back into obscurity.

Bibliography

Anderson, J.K. 1961. Ancient Greek horsemanship. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Anthony, D.W., and D. R. Brown. 1991. The origins of horseback riding. Antiquity. 65: 22-38.

Anthony, D. W., D. Y. Telegin, and D. Brown. 1991. The origin of horseback riding. Scientific American. 265(6): 94.

Clutton-Brock, Juliet, _Horse Power, A history of the Horse and the Donkey in Human Societie_s, Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, 1992,

Hyland, Ann, Equus: The Horse in the Roman World, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990

McMiken, D.F. 1990. Ancient origins of horsemanship. Equine Veterinary Journal. 22: 73-78.

Sturdy, Beck, The History of the Arabian Horse, Internet

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!