Stories connected with the Hejaz Railway

The Dominican Fathers

Father Lagrange of the Ecole d’Etudes Bibliques

Account of the trips taken by the Dominican Fathers of the French Ecole d’Etudes Bibliques (School of Biblical Studies) in Jerusalem on their way to the Nabataean sites of Petra or of Medain Saleh, or after WWI in Transjordan generally.

Collected and translated by Dr Geraldine Chatelard, Institut français du Proche-Orient, Amman

References:

RB = Revue Biblique (the scientific organ of the Ecole d’Etudes Bibliques, still published today) Mission I and Mission II = refer to two volumes of Mission archéologiques en Arabie (Archaeological Missions in Arabia), undertaken in the spring on 1907, 1909 and 1910. Republished in Cairo in 1997 by IFAO (French Institute of Oriental Studies)

Spring 1907

[The Darb el-Hajj] is a very well-marked caravan road also offering, from time to time, some reference points. They are the qalaah, in the old days stores as much as strongholds, established more or less regularly from stage to stage across the vast solitude. In the days of the pilgrims, provisions were accumulated there and water was prepared long in advance to supply people and camels. There is generally a well with a water-lifting device in the middle of the qalaah. Where the underground water table was insufficient, immense reservoirs were dug into which the flow of a wadi was directed on the days of winter rain. In many places, such as Qalaat Zizeh, Qatraneh etc. these reservoirs that have long been in bad condition have just been repaired and water points have been put in nearby for the locomotive. In this way the new engineers profit as much as possible from the work of their predecessors. (Mission I, pp 32-33)

1909

On Monday 15th of February 1909, at half past eleven at night, we took the train from the station in Amman to Maan, where we arrived the following day at five o’clock in the evening. It was at the time of the Hajj, that is to say the big pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina, when all the equipment was put to use for the transportation of devout pilgrims. Several trains went by each day, either going up or down. We traveled on the post train, that is to say the train for regular passengers, which leaves Damascus three times a week. At the back there is a first class carriage for the officers and effendis, all the other cars are open and already loaded with merchandise. We heave our baggage and ourselves onto a goods wagon where five or six Tunisians have already set up home in the midst of a load of planks. Our mode of transport might lack some comfort, but, if not for the terrible smoke and black rain that flooded our carriage near the tender, we would not have too much too complain about. After all, it is neither commonplace nor without interest to cross the desert on the upper deck. (Mission II, pp3-4)

23 March 1907

Maan railway-station is one of the most important on the Hedjaz railway. The director of works, Meissner Pasha, has established his residence there, and depots for materials and coal, even workshops for repairing the machines, have been built there. Its importance will grow when the project to make a branch line to Aqaba is implemented, which will connect Damascus directly with the Red Sea and allow rapid communication with Yemen, without passing through the Suez Canal. A dozen buildings of dressed stone, covered by red tiles bearing the stamp of Marseille, stand in the most absolute solitude near the little spring of Ain Kalbi. That place, which until recently was frequented only by a few nomads who briefly pitched their tents there, has become the abode of working people, employees, labourers and soldiers. There is even a hotel for the convenience of all these people and for travellers going to Petra by rail. (Mission, I, p. 33)

Spring 1909

55 kilometres south of Maan, Qalaat el-Aqaba - that is not to be confused with the place of the same name on the Red Sea - enjoyed a certain fame because of its position. Regardless of the administrative divisions, that have changed a lot, from the point of view of the physical landscape, it was the last post in the lands of esh-Sham [Syria]. There, the Syrian pilgrims camped for the last time in their own country, and prepared themselves to confront a desert longer and more terrible than the one they had already crossed. Indeed, its entrance was not reassuring. Having wandered some time in the hills with restricted views on all sides, they would fall into the Batn el-Ghul, the ‘belly of the demon’. That is the name given to what is indeed a demonic pass by which one descends to a lower level that marks the beginning of the Hedjaz. The engineers had to build a railway through this precipice. They managed by means of detours and cuttings, but the slope is still considerable and we descend with alarming speed which inspires legitimate fear. There have already been some derailments. Luckily the train drivers learn little by little and the passenger becomes absorbed by the beauty of the countryside. We travel amidst variegated sandstones of all colours, but dominated by yellow with black of a steely grey tint. The spectacle is splendid and the wildness of the place adds to its charm. (Mission II, pp51-42)

At last we arrive at the railway station of Wadi Retem without problem. The soldiers at this post and others in the vicinity of Batn el-Ghul spend their leisure time grinding up pieces of different coloured sandstone and putting the multicoloured sand into bottles, which they mix into thousands of bizarre designs with the help of a piece of wire. These curiosities are then sold to the engineers and passing officers, or sent to Damascus where collectors are more numerous. (Mission II, p52)

Spring 1909

The railway-stations between Maan and Tabuk are usually small houses for the work teams, with the entrance opening away from the rails, and a gallery along the front. Almost wherever there is water, wind powered pumps have been installed. A few of these machines come from America, but the majority of them are of German origin. (Misssion, II, p. 4-5)

Easter 1924

About ten of Emir Abdullah’s soldiers occupy the station of el-Fedein, whose official name is el-Mafraq (el-Fedein is the name given by the bedouins to the ancient station of the Darb el-Hajj, where next to the old [Aramaic] ruins are an Arab castle and a now abandoned pool). Partially filled trenches on the hillocks beside the station and the water supply, the windowless and roofless buildings, the ruined reservoir and the skeletons of several railway wagons lying near the tracks remind the traveller of the Great War. There is still water in the birkeh [reservoir] to which many herds of the Beni Hassan come to drink. (RB, 1925, p113)

April 1928

El-Qatraneh comprises a railway-station, a few mud brick structures with a stock of benzine, a pool and a relatively recent small fort which Ibrahim Pasha had armed with three small canons. Its status as the station for Kerak, situated 45 kilometres to the west, gives it some importance, especially since a real road, edged with drainage ditches and kilometre markers connects Kerak with the railway. In the old days, guides estimated 7 hours 50 minutes walk between Qatraneh and Kerak; today the journey is usually done in 1 hour 20 minutes. (RB, 1928, p598)

-——————————

The Amman to Damascus Trip

It is possible to take the Hejaz Railway from the Mahattah station in Amman to the city of Damascus. This is a trip that all old train enthusiasts will want to take. However, if you cannot afford to fly to Amman and take the trip, these pictures will have to suffice. Special thanks to Peter Herrett who took the trip in the fall of 2003.

The Mahattah train station in Amman. Taken from across the street.

The Hejaz Jordan Railway is reached through this very unimposing doorway. However, inside there are many delights for train enthusiasts.

The passenger terminal

An unidentified ruined locomotive

Locomotive no 23 (Robert Stephenson and Hawthorn S/no 7431, 1951

Data plate of Locomotive 23

General View from the Amman platform with Water towers at the station

The Data plate of 71 (Haine St. Pierce S/no. 2144 1955)

Unidentified locomotive

Amman Railway Museum

Inside the Museum

Locomotive 51 steamed up for a demonstration run (Arn Jung S/no 12081 1955)

Inside the cabin

Inside the cabin with the assistant driver

A Carriage

Damascus train ready to depar

All Aboard!

The Damascus Train in Al Zarqa with an American diesel

Passing through Dara'a Station. Locomotive Serial Number 9010 (Number 161)

Dera'a Train works

Locomotive 62 outside of the Damascus Station

Inside the Damascus Station. Since this time the station was badly damaged during the fighting 2010 to 2018

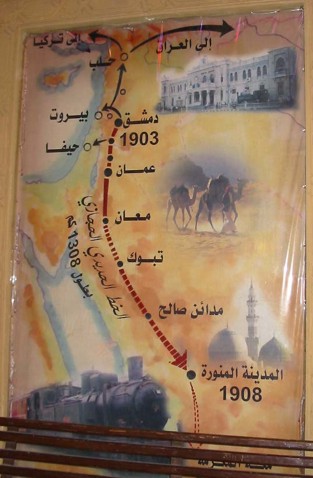

A map of the Hejaz Railway in the Damascus Train station

The Interior of a first class coach, complete with a heater.

Un-serviceable locomotives beside the Cadem workshop

-——————————

Jim Easler, Saudi Trip

In 1965, I was a member of the U. S. Military Training Mission to Saudi Arabia, stationed at the Saudi Army Air Defense School in Jidda. Most of us had heard of and seen pictures of Meda’in Saleh, The Nabataean tombs, and the Hejaz Railroad. We decided we would like to visit that area.

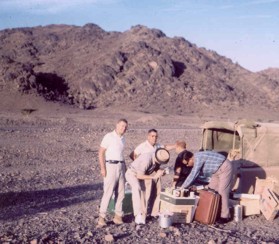

I prepared a letter to Prince Sultan, The Minister of Defense, and he granted us permission to make the trip and to use two Saudi Army Land Rovers. General Mansour Sha’iby, the Area Commander of Jidda, also detailed Captain Ibrahim Yosuf Omar of the Air Defense School, to accompany us as guide and interpreter. (Although two of us had attended the Defense Language Institute before going to Saudi Arabia. )

Our trip was made in November of 1965. We decided to travel and eat austerely so we gathered canned foods for each meal. We carried a 55 gallon drum of gasoline, none of us knowing just where gas would be available or how far apart service stations might be. As it turned out we found gas stations all along the route and had to resort only once to using that which we carried. We also carried cans of drinking water.

We left Jidda about 8:30 or 9:00 AM in the two Land Rovers and with Capt Omar driving his personal car. His wife was from Medina, and accompanied us that far. Members of our party were Major Everette Perrin of our Riyadh detachment; Air Force Sergeants Throckmorton and Weesmer both of the Jidda Air Section; Jim Kammert, a civilian employee of the Jidda office of the First City National Bank of New York; Capt Omar; and myself, Major Jim Easler of the Saudi Air Defense School.

We drove northward from Jidda along a first rate asphalt highway, passing numerous small towns most of which had food and gas facilities. Larger towns were Rabigh, about half way, and Badr Hunayn, where there was a fork in the road. The left fork went to Yenbo and the coast. We took the right fork northeast toward Medina. By late afternoon we reached the southern outskirts of Medina and Capt Omar called a relative who came out to meet us and drive Caot Omar’s wife to her family. (In Capt Omar’s car)

Capt Omar also called the office of the Amir of Medina (per instructions from General Sha’iby) We were given permission to proceed northwestward around the city along a route being prepared for paving a new highway that would bypass the city. We would come back to the main highway at the airport just north of town. We could then decide if we wished to continue on or remain overnight at the airport.

By the time we arrived at the airport it was dark and about 8:00 PM or so. Capt Omar called again and informed the Amir that we decided to stay the night at the airport. The Amir sent us out two big trays of food – traditional heaps of rice and meat. We had had our austere meal south of town but this food was much better and very welcome. We had come about 400 km from Jidda.

We took our sleeping bags up onto the roof of the airport. There was no night air traffic and there were only a few workmen around the whole facility. It was dark on the roof and the stars shone very bright with the absence of bright lights. We thought we were in for some uninterrupted rest..

About 11:00 PM we had the first of a number of “experiences” when two employees came to get our opinions on driving from Saudi Arabia to Europe. Was it best to drive through Lebanon, Turkey, and the Balkans or to drive through Egypt, all across North Africa, and cross over into Spain? We left it to them but suggested that the drive across North Africa might be worse, especially in summer

We arose early the next morning, getting away before the crowds came in and air traffic resumed. We headed north toward Al Khaybar, about 170 km away. South of Al Khaybar we ran into our second “experience.” Sections of the highway had been washed out by heavy rains and flash-floods.l Since our Land Rovers were 4 - wheel drive we were able to help several cars that had tried to drive through the rock and sand, back onto the roads.

As we left Medina airport, we gave a Bedouin a ride. He was going as far as Al Khaybar. He had an old bolt-action rifle that had seen better times. I didn’t get to look at it too closely as he seemed to be the sort of fellow who didn’t want anyone messing with his weapon.

When we got to Al Khabar, we went top the police station to ask about where we should turn westward off the main highway to go to Al Ula.

On the wall of the station were several pairs of old handcuffs and leg irons. The police told us that at a big bend in the road there was a road sign on the left side that someone had spray-painted “Al Ula” and drawn an arrow westward. This was a route that the truckers took out across the desert - only a track where vehicles had been driven.

We drove on northward to that sign, started out across the desert and in about an hour ran into another”experience.” This came in the form of a heavy downpour that included marble-size hail. The windshield wiper of the second Land Rover wasn’t working and we lost contact with each other. Fortunately we met up again after about 45 minutes of separation.

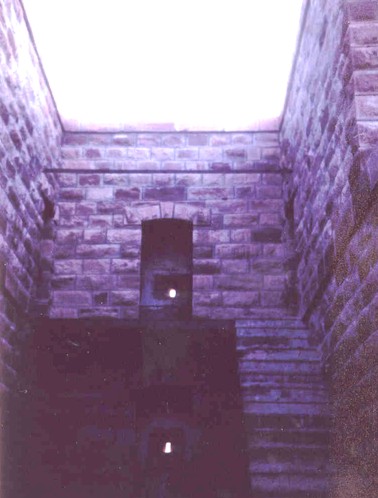

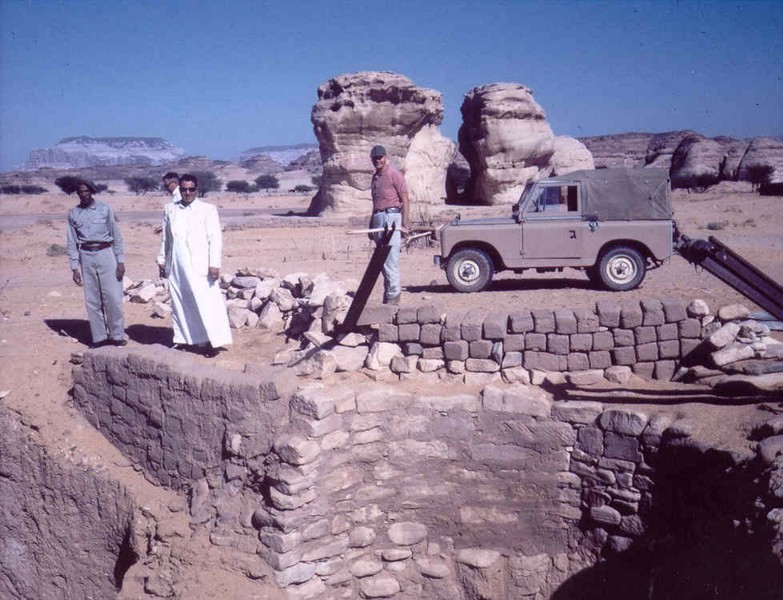

We drove on through the afternoon and finally came to the old Hejaz Rail Road roadbed at Qalat Zammurad Station. We stopped to look over the station - inside and out) It resembled more a fort than a railroad station. The rail line was being dismantled and there were stacks of rails and cross ties all around. The latter were not wooden like the ones we are familiar with but rather, they were made of iron. Most were in good shape even after nearly 50 years but suppose the arid desert air did not cause them to rust.. We also assumed that in days gone by, there was no chance of Bedouin digging them up to use as fire wood. We ate our snack supper and headed northward when we discovered that we had a flat tire. We would later be sorry we did not bring along extra mounted tires.

We drove on paralleling the railroad road bed as darkness fell. Later we saw off in the distance what appeared to be a string of lights. Eventually we came to Al Ula and found that, indeed, it was a string of lights – about a block or two of Coleman lanterns strung along the street. We drove to the buildings that had been a Hejaz Rail Road station and found that they had been converted into the offices of the mayor. There was a bit of consternation as he had not received a message of our coming. This was soon straightened out and he took us in and gave us part of a second floor “majless” (den) covered with Persian rugs. We brought up our sleeping bags and spent a blissful night.

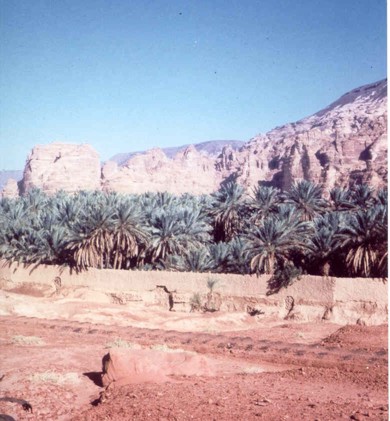

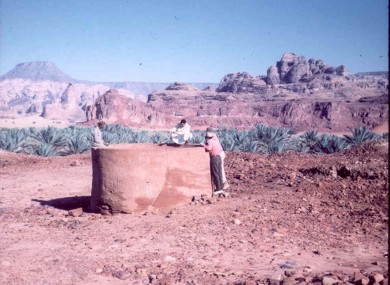

Wed awoke to a beautiful morning and immediately saw that Al Ula was literally an oasis. There were acres of palm trees in the valley around the old railroad and stark hills, mesas and far-off mountains. (Pictures show Al Ula RR Tracks, windmill anpve, & sunrise below.) Again we were treated to a meal as the mayor sent us breakfast – hot tea, pita bread, jelly, and good, canned Australian cheese. We were also informed that he would send a policeman along with us to Meda’in Saleh, as a guide. After breakfast and a short walk around the station we departed northward. We hadn’t driven long when we stopped at what would be a day-long succession of “experiences,” adventure, and wonder.

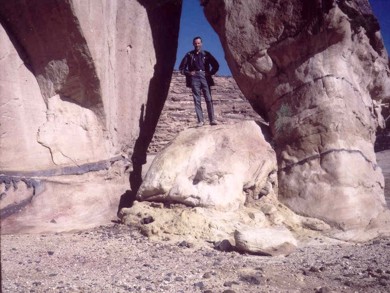

There was a huge, ancient cistern and behind it, stretching up into some hills, a large pile of rubble of stone and mud brick. It looked as if it had been a part of a town. These ruins seem to fit into an old story about a camel that I will relate shortly. (Pictures Below: Cistern, restoration of well, Me in the rocks.) We ambled through the ruins and one of our group found a flat piece of stone with an ancient writing on it. I found a stone about 1” thick and about 4” in diameter that appeared to be some sort of hand-held grain grinder. I also found what looked like half a stone mortar – about 8” - 10” long, 4” high, and weighing about 8 or 10 pounds. It had a bowl- shaped middle. (I later gave this to a member of the US Embassy in Jidda but I still have the grinder.)

Above: From this location looking to the west, we could see a great, blue mountain in the distance. We were told it was called The Mount of The Camel after a fable about the valley people and a she-camel. Seems the people shared the oasis with the camel lbut grew jealous of her even though she provided milk in abundance. They contrived to have her killed by placing spears along a narrow defile through which she passed. As the story goes, her “na’qa” baby camel, disappeared into the mountains – hence the name for the blue mountain.

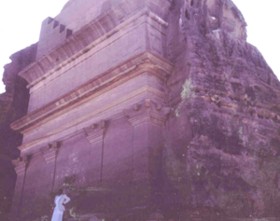

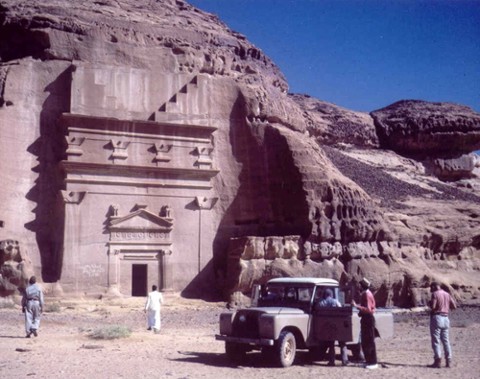

From the cistern and ruins we drove on a way and came out into a very wide valley – Meda’in Saleh. Everywhere you looked you could see the great facades of the tombs, cut back into the hills and cliffs. One was even cut into a single, sarge stone, called Qsar Farid.

We drove up close to several tombs and went inside. There were low ceilings and not much room inside. Strange’ these could have been the dwellings of cave-like people rather than tombs. Of course there was little to see inside. Centuries of travelers, tradesmen, Caravaners, pilgrims, and thieves had long since plundered the tombs. It was hard to imagine that people could cut and chisel these enormous caverns over 2000 years ago without modern tools.

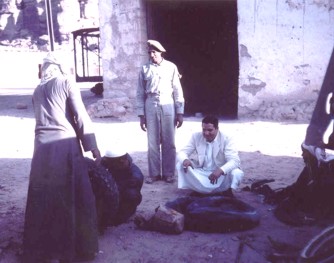

We spent about two hours looking around at the various tombs then headed toward the old Hejaz Rail Road repair shops that were in Meda’in Saleh. We found those in a state of ruin and abuse. Few tiles remained on the roofs. Doors swung on rusted hinges. But there remained in the shops, the skeletons of several box cars and the remains of an old steam engine. These must have been there for as many as 45 - 50 years – since Prince Faisel and Lawrence of Arabia raided the railroad or at least since the end of World War I.

What a day of surprise!!! We were seeing things that thousands of people had seen – but very few of them Westerners.On our way out of Meda’in Saleh we ran into a trucker who’s truck was off the road, in the sand where his young driver had driven it – with a broken axle. After talking awhile with him he decided he would ride back to Medina with us where he could get a new axle. We dropped off the policeman as we passed through Al Ula and thanked the Mayor for his hospitality

We drove southward to one of the stations between Al Ula and Qalat Zammurad where we decided to have supper. As we finished our meal, we noticed flat tire number two. Not knowing what we could run into further on, we decided that Capt Omar and I would return to Al Ula to get the tire fixed - we would then have one spare in good shape, We found the Mayor’s driver who agreed to fix our tire. He then found that the tube was ruin ed so we had to find a shop and buy a new one. With our fixed spare, Capt Omar and I set out to rejoin our comrades as it began to get dark.

Finally we made out a fire off in the distance. We blinked our headlights and saw lights blinked back at us — TWO SETS OF HEADLIGHTS!!!. As we pulled up to the old station, we saw another vehicle beside our Land Rover. Our friends had been joined, after our departure, by a group from the Saudi Ministry of Agriculture. They had brought out their tea kettles and coffee pots and settled down to keep our friends company until our return. Major Perrin had been able to talk some with them as he had attended the Def Lang Inst in California. It was also found that the elder of their group had been a telegrapher with the Hejaz RR and knew Morse Code. Sgt Throckmorton had aircraft radio experience and the two of them had exchanged a few phrases and entertained each other by tapping on the fender of the truck.

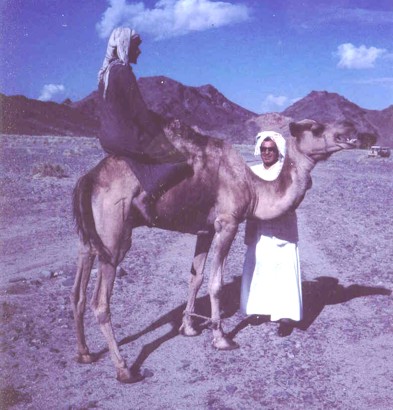

They offered to accompany us back to Al Ula or to let us have one of their spare tires. We turned both offers down and after they departed, we drove on to Qalat Zammurad Station. We brought out our sleeping bags and folding cots and spent the night by the old railway bed. The n ext morning we had breakfast and started for Al Khaybar. We had considered going by way of the rail line but decided that we knew nothing of the type road we may find. We came across two men and a camel They offered us rides on the camel. Capt Omar tried - they had no saddle - by holding on from the rear of the hump. The camel was a rather disagreeable sort so the rest of us passed on camel riding.

The rest of the trip was uneventful. We dropped the truck driver and Capt Omar at Medina. It was about 10:00 PM when we made it back to Jidda.

It was a fast, hectic, trip but we enjoyed the various experiences we had, the people we met, and especially getting to see the remains of the Hejaz Rail Road and the Nabataean tombs. My Army travels, schooling, and adventures were of great help after I retired and became a high school history teacher in Greenville, S. C. JIM EASLER; Lt Col; US ARMY RET

-——————————————–

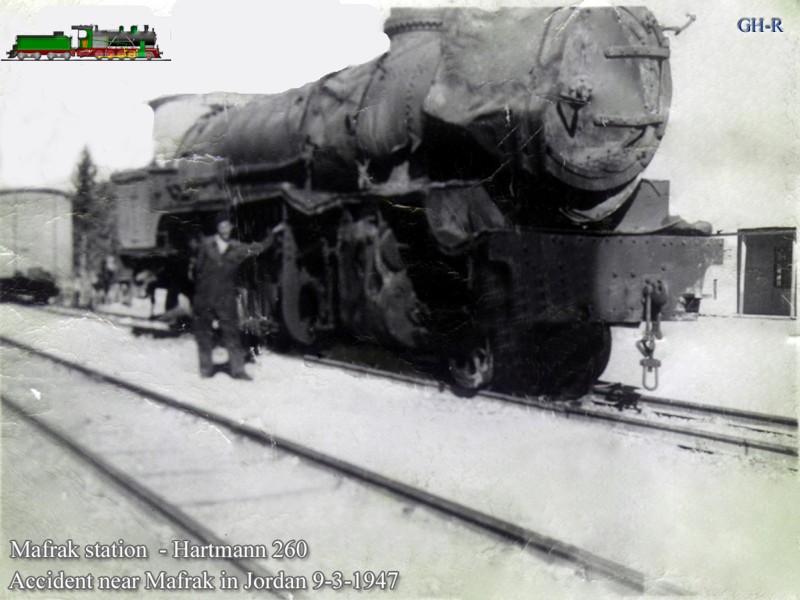

The Train Crash of 1947

As told by Mr. Aziz

It was the 9th of March, 1947 and that night the weather was very bad. A cargo train was gong south from Dera’a to Amman. There were 10 cars behind the steam locomotive, a Hartmann 260. There had been heavy rains that day, and the bridge before Mufraq had been damaged from the rains and the flash flood. The 3rd and 4th arch washed out from under the bridge. The driver didn’t realize that disaster was coming to him as the locomotive began crossing the bridge. He couldn’t see the missing arches under the rails. The locomotive suddenly plunged through the bridge with six cars falling ontop of it. The last four cars remained on the tracks. Fortunately no one was killed although some were wounded. This was the largest accident on the Hedjaz Railway.

Crash of 1947

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!