Click below to watch the video:

Transcript

While writing the book: Early Islamic Qiblas, it became increasingly evident that the original Qiblas of Umayyad mosques faced either to the city of Petra in Jordan, or to a spot half way between Petra and Mecca in Saudi Arabia, or to Mecca itself. With this in mind, I investigated and additional twenty three Umayyad structures (not mosques) to see if they had similar Qibla directions.

Muslim armies entered Jordan in 629 CE and met a large Byzantine force at the Battle of Mu’ta in southern Jordan, about a hundred kilometers north of Petra.Seven years later, at the Battle of Yarmouk they took control of Palestine, Jordan and Syria and ruled this area until the Abbasids assumed control. In total, the Umayyads controlled this area for around 120 years. During this time, extensive building projects took place, many of them surviving in some form until this day. As these buildings generally fell into ruin after the Abbasid takeover, their foundations remain, and we can examine many of the original structures without later buildings removing any evidence of earlier buildings on the same site. However in a few rare cases newer structures were built on top.

In order to prepare a list of Umayyad structures, I used data from my previous Qibla research plus a number of buildings listed in the paper: *Improvement of Mediterranean territorial cohesion through setup of tourist-cultural itinerary Umayyad, by Naif Haddad, with contribution from Bilal Khrisat, prepared by CulTech Team, 2014-2015*. In many cases the buildings were visited by me or one of my associates. I also used some satellite imagery, first to confirm the measurements made on the ground, second to make observations of buildings I had not visited, and finally for the purpose of illustration.

With each of these structures, I tried to identify the Qibla direction of the structure, and compare it with the four Qiblas: Petra, Mecca, Between, and Jerusalem.

Note that the Qibla Database, known as the online Qibla Tool (https://nabataea.net/explore/founding_of_islam/qibla-tool/) also compares these Qiblas with summer and winter solstices.

When I included these Umayyad buildings in the Qibla Database, I experienced some resistance from a handful of Muslims who objected to Qibla data being included from structures that were not clearly mosques with a miḥrab niche. In this short video (and accompanying paper) I will try and explain why these structures were included and what we can learn from them.

The invention of the Miḥrab niche

After Ibn al-Zubayr’s rebellion and the death of Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik in 86 AH (705) Al-Walid I became the Umayyad caliph. New mosques were constructed inṢan’ā, Yemen, Khirbat al-Minya, (Jordan Valley) andḤajjāj b. Yūsuf began his Between mosque in Wasit, Iraq.In 88 AH the Mosque of the Prophet in Medina was torn down and rebuilt, and the Qibla wall changed. (Tabari Vol. 23, pg 141). It was during this rebuilding that the miḥrāb mark or niche was introduced and then began appearing in new mosques and added to old mosques. It should be noted that up until this time there was no question as to which direction the faithful should pray. Entire building faced the qibla, with one wall designated as a qibla wall. Now, however, the miḥrab niche was added to old buildings and mosques as well as used in new mosque construction to clearly indicate which of the four Qiblas was intended at that location. Here is a quote from the Encyclopedia of Islam.

The first concave miḥrāb, i.e. miḥrāb mudjawwaf, was introduced by ‘Umar b. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, governor of Medina, when he rebuilt the Prophet’s Mosque between 87- 88 AH or 706-707 CE.(al-Maḳrīzī, Khiṭaṭ, ii, 247; Ibn Taghrībirdī, al-Nudjūm al-zāhira, i, 76). It was richly decorated with precious material (Sauvaget, 1947, 83-4). After that, the semicircular miḥārīb spread throughout the Muslim world. Such a miḥrāb was introduced into the Great or Umayyad Mosque at Damascus when al-Walid I took over the entire building and rebuilt it between 87 and 97 AH. (706 and 714-15 CE) According to early accounts, it was set with jewels and precious stones. This miḥrāb was destroyed in 475 AH (1082) and then was subsequently rebuilt but destroyed again by fire in 1893 CE. The third concave miḥrāb was built in the Mosque of ‘Amr at Fusṭāṭ in 92 AH (710 CE). Semicircular miḥārīb flanked by pairs of columns were found in many of the Umayyad desert palaces (Creswell, 1932, fig. 438, pl. 120b, e; idem, 1969, i/2, figs. 538, 638, pls. 66 f., 103e and 115b). The earliest surviving concave miḥrāb in a mosque is, according to Cresswell, in the Mosque of ‘Umar at Boṣrā, built during the late Umayyad period (1969 i/2, 489, fig. 544, pl. 809).

The above is taken from the Encyclopedia of Islam II, Vol. 7, pages 8-9; article by G. Fehervari.

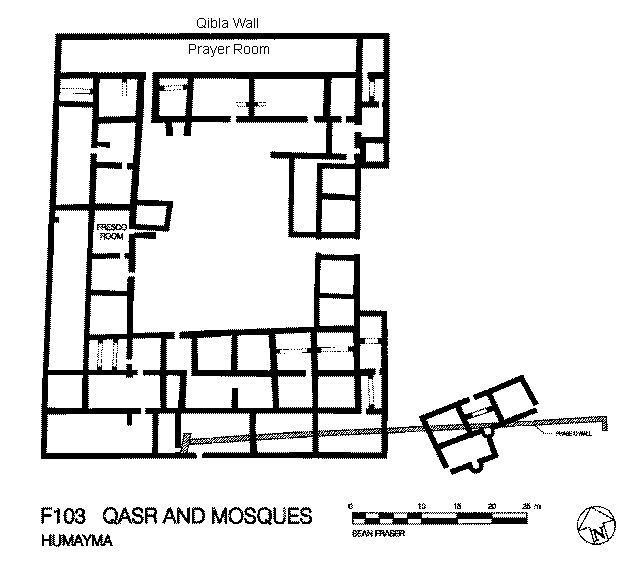

According to the Dictionary of Islamic Architecture (Petersen, 1999, page 32) the first concave miḥrab niche was introduced at Medina between 707 and 709 AD. Before this (for 89 years) mosques did not have a distinct niche in a wall that indicated which direction the faithful should pray. Rather, early mosques simply had a qibla wall that the faithful faced during prayer. Most buildings were not perfectly square, so while the entire building roughly faced the qibla direction, one wall was specifically considered the Qibla wall.We can see this at Humeima, where the side walls and the south wall have different orientations and angles, but the north wall is clean and simple, and it faces towards the Ka’ba in the city of Petra, some 27 miles away. In this Qasr the Qibla faces north and there is a long wide prayer room that is immediately accessible for everyone via a hallway from the centre courtyard.

Humeima Qasr floor plan

Now that is important as the mosque or prayer area needed to be accessible to everyone, especially the visitors who had just come in.

According to the information I have collected (displayed in the online Qibla tool) over 20 major mosques and Qasrs were constructed in the years before the miḥrab was introduced.

What is of prime importance to us, is that that most Muslims, and even many historians, will only consider a location a place of prayer, if they find a miḥrab niche. This unfortunately does not allow them to identify any buildings as mosques or places of prayer prior to 709 AD, or after the first almost 100 years of Islamic history.

The Development of the Qasr The Qasr was a unique building, much more reminiscent of large commune or of the earlier Nabataean manor houses. These buildings did not suddenly appear near the beginning of Islamic history. These buildings have a long history of use among the Nabataeans, the people who built the city of Petra. Incidentally, to my knowledge, no Umayyad Qasrs are found in Saudi Arabia. They are found mostly between Petra and Damascus.

So let’s consider the Nabataean villa houses that preceded the Umayyad Qasrs. The first thing to notice is that these houses were large. There are some surviving Nabataean manor houses in the Nabataean city of Mampsis, in the Negev. A smallest private dwelling in Mampsis covered an area of 700 square meters (7,535 square feet) per house! The largest was over 2,000 square meters (21,528 square feet). There is also a building in Mampsis called a palace, as it was named by the archeologists who discovered it, and there is no indication that it ever was a palace. The archeologists were impressed with its size so it seemed like a palace to them. It occupied an area of 1000 square meters (10,764 square feet), and it also had a massive watch tower. All these houses were two and sometimes three stories high, which added to the usable living space. From their construction, it seems that each of these houses was made to accommodate one extended family. Of course, wealth had much to do with the construction of dwellings of these dimensions, and their huge size is unique to Palestine.

These manor houses or villas or mansions had excellent quality masonry and sometimes extensive architectural decoration. In Mampsis, both the palace and the private dwellings were built as self-contained fortresses, with rooms around central courts. Each unit had only one entrance, and the outside walls were solid with narrow slots high up on the wall. All houses had at least two stories, and those above ground level were reached by means of towers in which the stairs were built around a heavy pier. A balcony sometimes surrounded the inner court. There were also storerooms and stables on the ground floor. The roofing system was based on arches with cover-stones, but the courtyard in the middle was open. There was at least one cistern for each house. The public reservoir was large, about 18 x 10 meters and was roofed over by arches resting on piers. The water storage consisted of series of dams, in which flood waters were transferred to public and private reservoirs in the town. A clip from a drone flying over the ruined city of Mampsis can be found at: https://youtu.be/0bLwd-Zm46Q. The large building at the bottom of the screen is a caravansary, or a sort of inn for passing caravans to spend the night.

Now below I have a chart that compares the size of the early Nabataean villa houses. Note that all measurements are approximate, within a foot or twp of accuracy. The Mampsis House, and the Petra Manor were built several centuries before the Umayyad Qasrs. But there are striking similarities between them.

- Nabataean Mampsis House: 123 X 128 feet (30 meters x 35.5 meters) or 15,750 sq ft

- North of the city was a Caravan Inn. 80 X 170 feet (23.5 X 52 meters) 13,600 sq ft.

- Petra Manor House : 104 X 116 feet (33 X 36 meters) 12,064 sq ft.

So these buildings were over 100 X 100 feet, making them all over 10,000 square feet. The house that I live in, in Canada, is only around 1000 sq feet. So my house is 1/10th of the size of those houses. Now let’s look at the Umayyad buildings built several hundred years later.

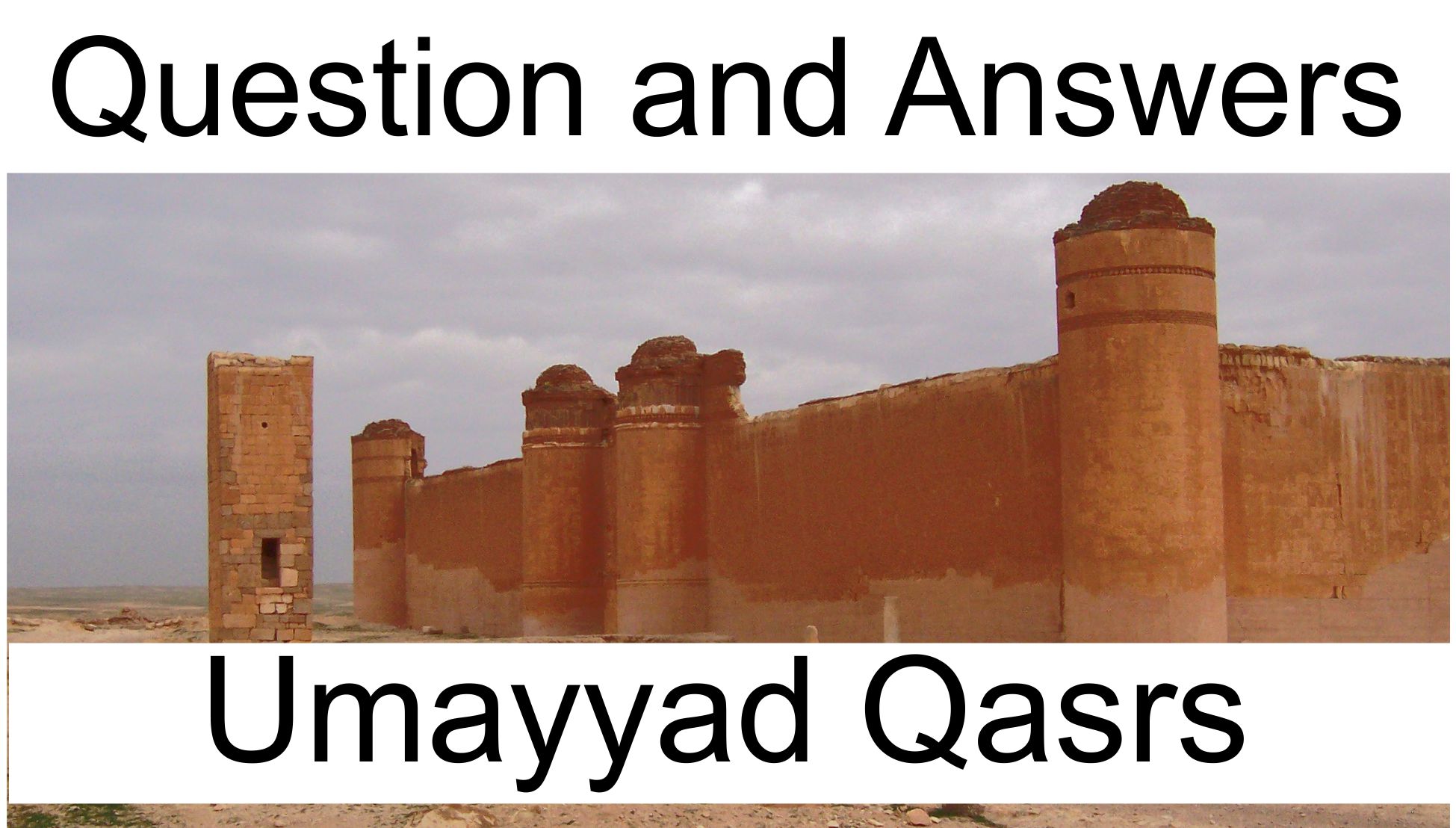

Umayyad Qasrs

- Humeima House 200 ft x 160 feet (48.5 X 62 meters) 32,000 sq ft.

- Um Walid Eastern Qasr 230 X 228 (70.5 X 70 Meters) 52,440 sq ft.

- Um Walid Western Qasr 155 X 150 feet (48 meters X 46.5 meters) 23,250 sq ft

- Qasr Qastal 230 X 225 feet) (70 meters X 68.5) 51,750 sq ft.

That means my house is 1/50th of the square footage of this house! Notice that the Qasrs all retain the same shape as the earlier Nabataean mansions. They had but one entrance which led to an inner court; had functioning rooms on the lower floor and living accommodations on the second floor. The Umayyad Qasrs were all built by powerful families who had considerable influence. The big difference between the Umayyad Qasrs is that they were not agreed on the Qibla direction. They all faced one of three different Qiblas: Petra, Mecca, or the Between position.

Now let’s look at Qasrs in a bit more detail:

As I said earlier, Qasrs were built in a large square shape, with an open central courtyard. Usually there was only one primary entrance, flanked by guardrooms. This entrance opened into the central court. All of the rooms around the courtyard opened into the central court, with few windows facing outward. All of this gives the Qasr the appearance of a military structure. And indeed these structures were often built at the intersection of local trade routes. Sometimes Qasrs were built within view of each other, to provide a line of structures that could signal and support one another. Now a few of the Qasr locations began as Roman buildings, then perhaps were converted into Byzantine monasteries, and later were totally rebuilt as Umayyad Qasrs. Each of these transitions was usually accompanied by the builders tearing down the previous structures, setting a new foundation and then using the older building materials in the new structure. Earlier sites were chosen because of access to water, proven strategic locations, and especially because of ready-made building materials at the location. Many Qasrs had external gardens, orchards and agricultural land around them. Some Qasrs had additional bath-houses for the wealthy and smaller residential buildings for the agricultural workers to live in. It appears that these agricultural workers did not live or function from inside the Qasr, but were restricted to areas outside. We can see this at Qasr al-Hayar-al Gharbi, and Humeima.

In the case of Humeima, the archeologists excavating the site were aware of Islamic accounts that tell us that the Qasr was the home of the famous Abbas family. However, when they excavated the manor house they did not find a miḥrab niche. Unaware of the Petra option, they began looking farther and farther afield for a mosque.

Initially they had disregarded a series of small building to the east of the Qasr, because it was obvious to them that these buildings were the homes of the agricultural workers who worked the fields and orchards that were watered by the nearby wadi. However, on the last day of their dig, the archeologists examined the small outer buildings and discovered a small room in this complex that had a mihrab niche. But there were problems. The miḥrab could only be noticed by a single layer of stones placed on the ground. The rest of the building was missing. Probably later Bedouin had stolen the stones to use in their own construction. If you look at a satellite photo you can see multiple walls indicating various stages of residential developments over the years. (Bottom right corner)

Humeima Qasr

I visited this Qasr several times over the years that the archeologists we excavating. It was one of the closer excavations to where we lived at the time. During those visits I noticed that the small mosque had different miḥrabs at different times. It seemed to me that they could not decide how to place the miḥrab stones. Of course, once some well meaning Arab had realigned the stones to a ‘better’ position, the original setting of the stones was lost. I have searched my photos for pictures of the various miḥrabs, but unfortunately none have survived from those visits.

Qasr Life Life in the Qasr was focused on the central courtyard. This yard was the main way of connecting when moving from one part of the Qasr to the other. Basically, you went outside, through the courtyard and then into another part of the building. Many of the Qasrs also had a second story, usually with a balcony around the central courtyard. Some had access to the roof so that the building could be defended from above. These central courtyards were places where people gathered, animals were handled, grain and fruit supplies were brought in, large cooking events took place, and the courtyard was the place where the faithful would gather to pray or that had immediate access to the prayer room. A mosque or a prayer room in the Qasr had a door into the central courtyard. You didn’t go through private living quarters to get to it.

Prayer places located inside the Qasr It appears that the very first Qasrs had no additional mosque outside of the structure. We can see this from: Khirbat al Minya and Al-Kharana and other early Qasrs. Since the miḥrab niche had not yet been invented, there was no marking in on any walls to indicate that they were specially designated as a place of prayer. Instead, it appears that the open central courtyard which was common to all was used as a place of prayer, or that a special room was used that was immediately behind the large flat wall which was deemed the Qibla wall.

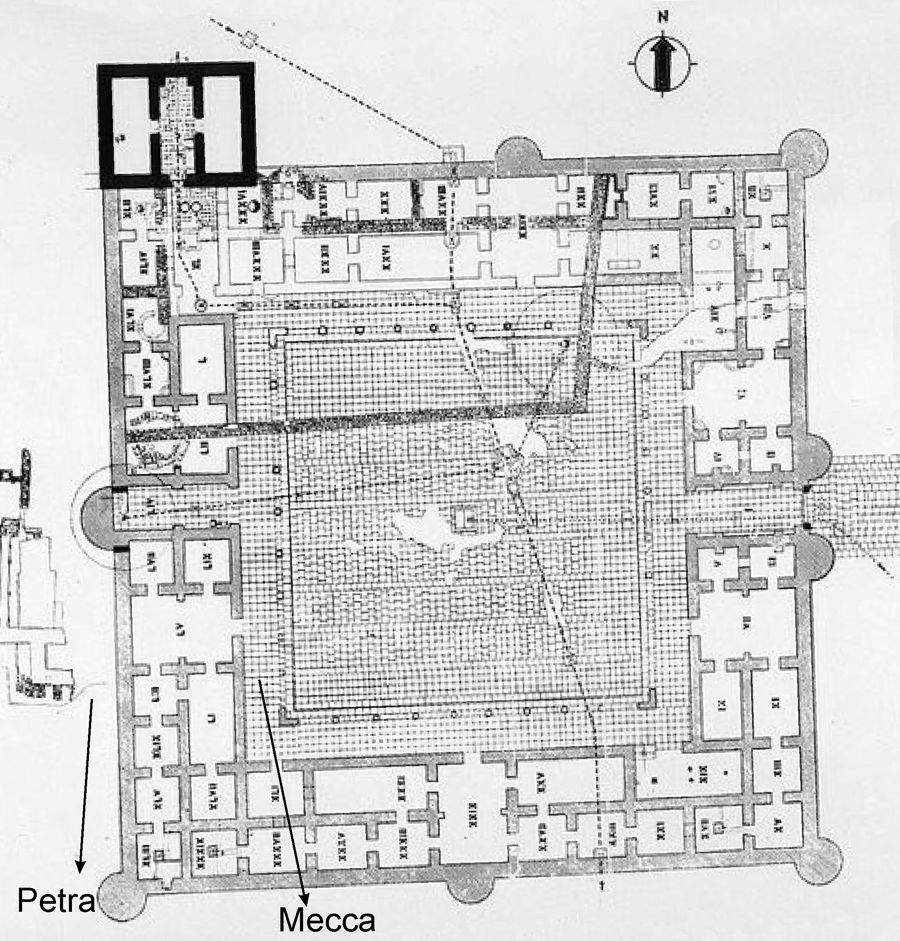

Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi

Above we can see a drawing of Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi. The Qasr is oriented towards the between position. The archeologists discovered a very small room (lower left hand) with a small miḥrab. Because this was the only room with a miḥrab they only labeled this one room as a mosque. However, this room was not accessible from the main courtyard, and was probably only used for women or was a personal prayer room. The most obvious prayer room was the one in the very center of the south wall, accessible to the main courtyard, with doors leading to the right and the left. Any of the other rooms, or even the south end of the courtyard could have been used for prayer, as the entire building was constructed so that the rooms were aligned to the Between Qibla position. The Change of Qibla

As we have already mentioned, the miḥrab niche was developed around 89 AH, right about the time that there were three different Qiblas in use in the Muslim world. With these changes, old mosques needed to be changed. Also, Qasrs needed to be changed as well, especially if the leading families had now agreed to change their direction of prayer.

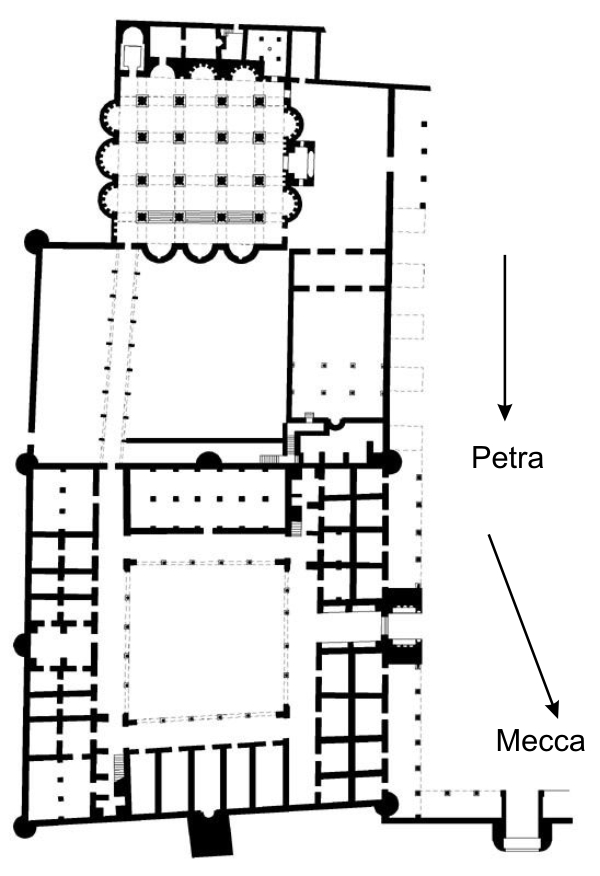

We can see this in the town of al-Walid. Here there are two Qasrs. It seems there were to two families but they did not agree on everything. The original Eastern Qasr was built facing the city of Petra like all the earliest Qasrs.

The other family, or a split off from the main family built themselves a new Qasr not too far away. That Qasr is known today as the Western Qasr. But it does not face Petra. Rather it is oriented towards the Between position.

Well a short time later the Mecca Qibla became the most popular, so the family in the eastern Qasr built an external mosque for those who wanted to pray towards Mecca. So here in one town we have evidence of all three Qiblas distinctly demonstrated in the architecture of the town.

Satellite photo of the town of Walid with two Qasrs and a mosque.

Some Qasrs however chose not to build external mosques. Once the new Qibla was developed they tried to modify the Qasr itself. We can see this at Khirbit al_Mufhar.

Khirbit al_Mufhar

The original Qasr interior courtyard (north part of the Qasr) faced south towards Petra.

But later a specific room in the southern part of the Qasr was chosen for a mosque, and a hole was knocked into the wall to incorporate a Miḥrab.But with the wall severely weakened the structure, the builders had to significantly reinforce the wall. Once can see the attempt to turn this Qibla towards the Between Qibla.

A List

There are over Umayyad structures that are not constructed as mosques but are included in the Qibla Tool database.I believe this list demonstrate that these buildings were all constructed with Qibla direction in mind, and incorporated into the orientation of the structure. On the website I deal with each structure individually. When using the Qibla tool, check the link: More Info.

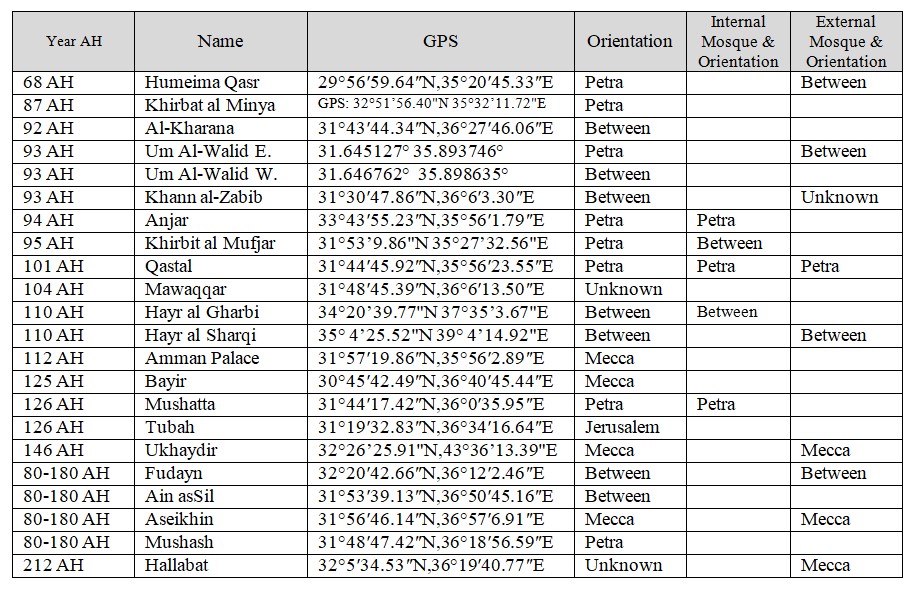

The table below lists these Qasrs in chronological order.We can see that there are 10 of these structures with no accompanying mosque. In each of these cases, the structure itself is oriented towards a Qibla, as indeed are 17 of the 21 structures.

Chart of Qasr Qiblas and accompanying mosques

So in this video I have introduced you to the more than 20 Umayyad Qasrs between Petra and Damascus. When considering all of these Qasrs together, we can trace certain patterns. The large size, the central courtyard, a single gate, the lower floor being a working area, and the upper floors being the homes of the extended family.

The first Qasrs did not have separate mosques, and many never did have a mosque. Some Qasrs developed internal prayer areas, but in 9 instances an external mosque was built at a later date, sometimes with a different more modern Qibla than the original Qasr had. The earliest Qasrs were oriented so that they had a Qibla wall facing Petra. Later some Umayyad Qasr were constructed with a Qibla wall facing the Between position, and finally, four of the Qasrs had a Meccan Qibla. In every case, the Qasrs were oriented towards once of these three Qibla directions.

I am Dan Gibson, and this has been another video in the series: Archeology and Islam.

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!