Click below to watch the video

Archeology and Islam #2 The Between Mosques do not face Mecca in Saudi Arabia. Who built them and why?

Transcript

Video #2 This is a general transcript of a Dan Gibson video in the series: Archeology and Islam.

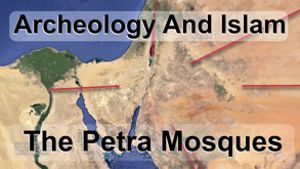

Hello, and welcome to another video is the series Archeology and Islam. During my studies of Early Islamic Mosques I discovered that the earliest mosques did not face Mecca in Saudi Arabia, but faced Petra in Southern Jordan.

Then, 87 years after the Hijra, a mosque appeared that faced an empty deserted spot in Arabia, located directly between Petra and Mecca. During the next 70 years, 14 other Umayyad mosques used this “between” Qibla direction. As research is ongoing, perhaps more of these middle mosques will be discovered.

As far as I can trace, the first mosque with this orientation appeared in Wāsiṭ Iraq, around the year 87 AH. Now why would someone go against the grain and build a mosque with such a strange Qibla direction? During the first years of Islam, every mosque pointed to Petra, in Jordan.

After the 2nd civil war, Ibn Zubayr and the people of Kufa pointed their mosques to a barren valley in Saudi Arabia, known as Mecca. According to an inscription found in Saudi Arabia, soon after this a new Masjid Al-Haraam was built in that valley. And now, a man named al-Ḥajjāj bin Yousif Al-Thaqāfi pointed his new mosque to a another place. A spot directly between Petra and Mecca.

Lets backtrack a bit to the 2nd civil war. The caliph has just moved his capital city to Damascus, spurning the cities of Medina and Petra, which is called Mecca in later accounts.

Al-Ṭabarī tells us that: Ibn al-Zubayr demolished the sanctuary (Ka’ba) until he had leveled it to the ground, and he dug out its foundation …. He placed the Black Cornerstone by it in an ark [tabut] in a strip of silk. So the Umayyad armies of Damascus descend on Petra, and a major war begins that would last for several years.

At this point, al-Ḥajjāj entered the picture. The Umayyads sent him to put down the rebellion and restore law and order, and give access to the religious sites in the Holy City. Al-Ḥajjāj was an extremely capable and ruthless statesman, strict in character, but also a harsh and demanding master. He was widely feared by his contemporaries and became a deeply controversial figure, and later an object of deep-seated enmity as he did thing differently than the later Abbasid rulers desired. As we will try and demonstrate he was involved in the very controversial changing of the Qibla.

Al-Ḥajjāj was born about 661 AD or 41 AH in the city of Ṭā’if. His ancestry was not particularly distinguished: he came of a poor family whose members had worked as stone carriers and builders.

As a boy, al-Ḥajjāj acquired the nickname Kulayb (“little dog”) a name he could never shake. He originally became a schoolmaster in his home town, which was another source of derision to his enemies, who sought to be great warriors.

Soon after Marwan assumed the throne in 64 AH, al-Ḥajjāj left his home town and went to the capital, Damascus, where he entered the security force of the caliph. There he attracted Abd al-Malik’s attention by the quick and efficient way he restored discipline during a mutiny of the troops appointed to accompany the caliph in his campaign against Mus’ab ibn al-Zubayr in Iraq.

As a result, the caliph entrusted him with command of the army’s rear-guard. He apparently achieved further feats of valor, so that after the defeat of Mus’ab, Abd al-Malik decided to entrust him with the expedition to subdue Mus’ab’s brother, Abdallāh ibn al-Zubayr, in the Holy City.

The caliph had charged him first to negotiate with Ibn al-Zubayr and to assure him of freedom from punishment if he surrendered, but, if the opposition continued, to starve him out by siege. He was instructed not to shed blood in the Holy City.

When the negotiations failed al-Ḥajjāj lost patience, and sent a courier to ask for reinforcements and also for permission to take Mecca by force.

He received permission for both, Then he stared a catapult bombardment, and direct attacks. The war between Ibn al Zubayr and al-Ḥajjāj took place for six months and seventeen nights in the center of the city.

One witness said: I saw the manjaniq (trebuchet) with which [stones] were being hurled. The sky was thundering and lightening and the sound of thunder and lightning rose above that of the stones, so that it masked it. The Ka’ba was so damaged that it looked “like the torn bosoms of mourning women.”

The siege lasted for seven months and in the end 10,000 men, among them two of Ibn al-Zubayr’s sons, had gone over to al-Ḥajjāj. In the end Ibn al-Zubayr and his youngest son were killed in the fighting in a ruined building near the Ka’ba. And so General Ḥajjāj won the war. But many people were upset with how violent the attack had been, and that blood had been shed in Masjid al Haraam, whose very name, The Forbidden Gathering Place, meant that shedding blood, even of animals was forbidden.

As a reward the caliph made al-Ḥajjāj the governors of the Hijaz, Yemen, and al-Yamama. It was here that he began to persecute the Companions of Muḥammad by making them wear a lead seal around their necks. During his lifetime, Al-Ḥajjāj killed four companions (ṣaḥaba) of Muḥammad.

Despite these actions, in 75 AH Caliph Abd al-Malik appointed al-Ḥajjāj as governor of Iraq. This placed Ḥajjāj in a very powerful position, governing the entire eastern half of the caliphate. The following years were filled with bloody wars, putting down rebellions and ruling with an iron fist.

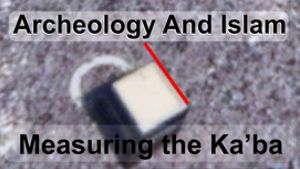

What interests us the most is the construction of the city of Wāsiṭ in the year 83 AH and Wāsiṭ al-Qaṣab in 95 AH. A number of interesting mosque constructions or renovations took place during this time. As archeological evidence now shows us, the Qiblas of these mosques did not all agree.

Some of the Between Mosques

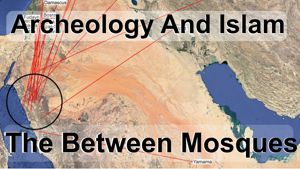

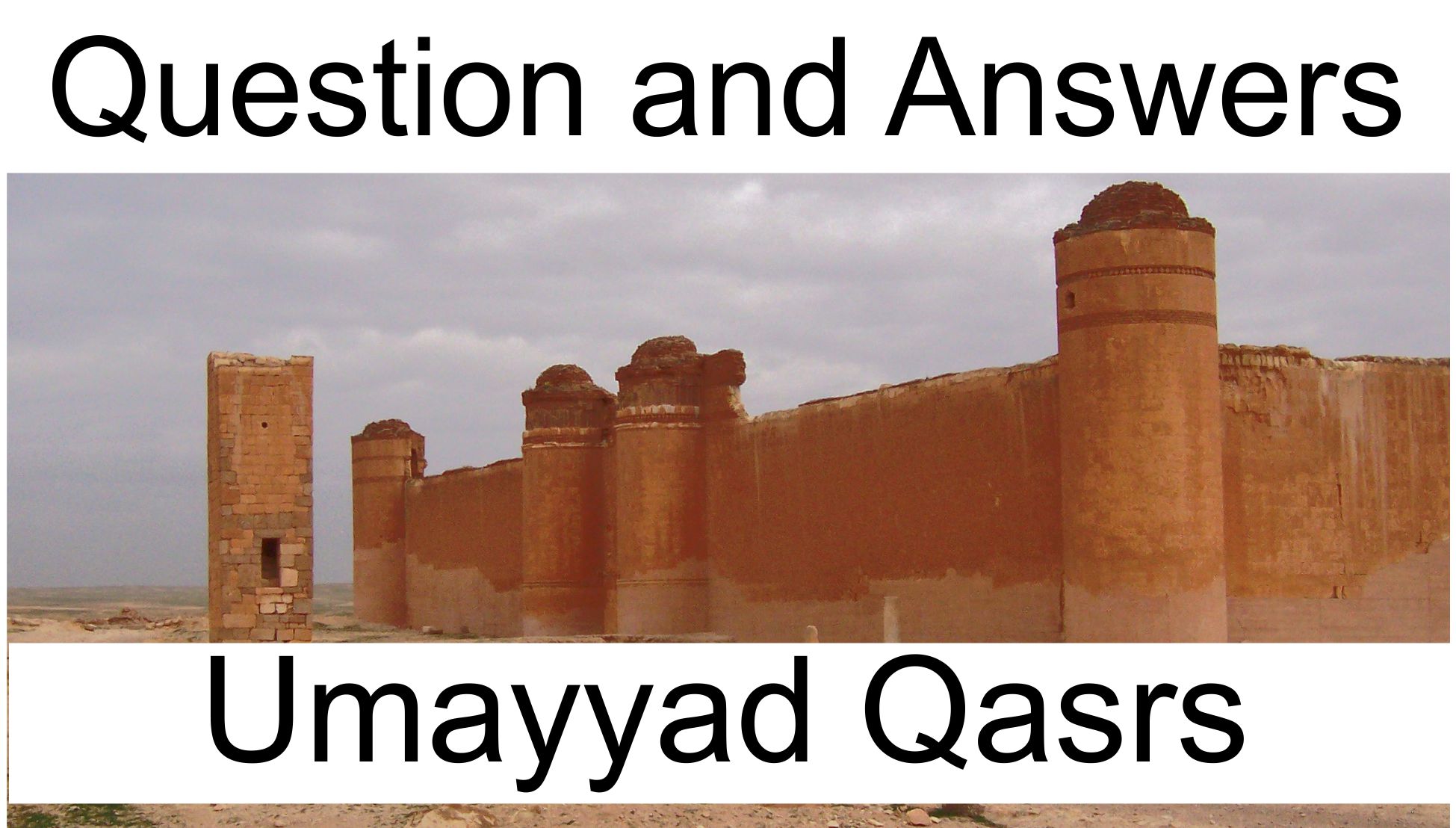

The first striking evidence is that al-Ḥajjāj’s mosque in Wāsiṭ faced a spot directly between Mecca and Petra. This was followed by other important mosques in Damascus, Boṣra, the desert palaces, the city of Ḥarrān, and even the main mosque in the city of Raqqa in Syria. At least 15 mosques, some of them major mosques were built under al-Ḥajjāj’s leadership, and they all faced a spot directly between Petra and Mecca.

Now why would he do this? If you think about it, al-Ḥajjāj would have disdained the original city, since he had fought against it and destroyed it. Smashing down the old temples, and destroying the original Ka’ba.

I am sure that he upset with the Block Rock being moved to Mecca in Saudi Arabia. And while some Muslims were embracing this new location for Mashjid al Haram, al-Ḥajjāj chooses his own Qibla, half way between the two. And he was criticized for it and be brought criticism down on Caliph Walid. Later writers such as Jāhiz includes the setting of the qibla of Wāsiṭ among the misdeeds of the caliph, as it began a dangerous precedent.

So how did al-Ḥajjāj convince the caliph to let him pick his own Qibla. Well, al-Ḥajjāj had an inside track. His daughter became the wife of Masrur, who was the son of the caliph.

What is astounding is that so many of the later mosques built under the Umayyads faced this between position. At the very same time, there were mosques being built that faced Mecca, and there were new mosques being built that face the old Qibla of Petra.

So what were the mosques?

- Wāsiṭ 87 AH in Iraq

- Damascus in Syria

- Boṣra in Syria

- Hayr al Gharbi in Syria

- Hayr al Sharqi in Syria

- Baalbeck main mosque in Lebanon

- Raqqa main mosque in Syria

- Ḥarrān mosque and university in Turkey

- Udruah Ottoman Fort in Jordan, not the Roman Fortress

- Khirbet Khan Ez-Zabib in Jordan

- Qaṣr Ain as-Sil in Jordan

- Qaṣr Al-Fudayn in Mufraq Jordan

- Qaṣr Kharna in Jordan And the ‘Azraq Fort Mosque in Jordan. Notice the mosque in the middle of the ancient fort. The mosque is oriented towards a place between Mecca and Petra.

Obviously General al-Ḥajjāj had a huge influence on the development of Islam during his lifetime. However, after he died, his influence waned, and the popularity of the new Masjid al Haram in Mecca grew. Eventually no one built mosques that faced the between position. And it was soon forgotten about. And we had no clue that this had happened, until archeologists and historians began uncovering the ancient foundations, and matching that with glimpses of things written in the historical records of the later Abbasids.

In much the same way, the Muslims of North Africa and Spain also refused to point their Qiblas at Mecca and chose rather to point their Qiblas south, most of them parallel to a line drawn between Mecca and Petra, and this became the fourth Qibla. It too only lasted a few years, before it passed out of use, and eventually every new mosque in the Muslim world pointed to Mecca.

And so the city of Petra, the between mosques, and even the parallel Qiblas of North Africa and Spain were forgotten. And every Muslim believed that all of their mosque Qiblas always pointed to Mecca in Saudi Arabia. This is why it is important to understand Archeology and Islam. Now that brings us to the question: When did the Qibla direction change to Mecca? Can we use the dates of mosque constructions to figure that out? And that is the subject for different video.

I am Dan Gibson and this has been another edition in the series Archeology and Islam.

Bibliography

Gibson, Dan, Early Islamic Qiblas, Independent Scholars Press, 2017

Al- Ṭabarī , Ḥajjāj b. Yūsuf , *The History of Al-Tabar*i, various volumes and translators, State University of New York Press

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!