Did the prophet Muhammad initiate the use of the Mihrab or did it come later? Why do the first mosques have no mihrab? What was used to indicate the direction of prayer before the Mihrab was invented, and why is all this important?

Transcript

Archaeology & Islam # 30 The Origin of the Miḥrāb

Hello, I am Dan Gibson, and this is another video in the series Archaeology and Islam. Our topic today is about the origin of the miḥrāb. When was it invented? Why was it invented? And what was used before it was invented?

For a long time I have felt a need to do write something about the origins of the miḥrāb because I cannot find it clearly laid out by any other writer.

In recent years, Andrew Petersen (1999) noted that the miḥrāb was a later invention, and was not used in the very earliest mosques.

Dictionary of Islamic Architecture

In 1999 Routledge published Petersen’s Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. In just over 300 pages, Petersen covers the major mosques of the Islamic world. (Peterson, Andrew, Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, 1999)

Remains of the Banbhore mosque

He addresses the Banbhore mosque on page 32 and notes: Significantly there is no trace of a concave or projecting miḥrāb which confirms the mosque’s early date, as the first concave miḥrāb was introduced at Medina between 707 and 709 AD. (88-89 AH)

In addition to this, Petersen has a dictionary heading on the miḥrāb: miḥrāb Niche or marker used to indicate the direction of prayer usually in a mosque. A miḥrāb is usually a niche set into the middle of the qibla wall of a building in order to indicate the direction of Mecca. The earliest mosques do not appear to have had miḥrābs and instead the whole qibla wall was used to indicate the direction of Mecca. Sometimes a painted mark or a tree stump would be used to reinforce the direction. In the cave beneath the rock in the Dome of the Rock there is a marble plaque with a blind niche carved into it which, if contemporary with the rest of the structure, may be dated to 692 making it the oldest surviving miḥrāb. The first concave miḥrāb appears to have been inserted into the Prophet’s Mosque at Medina during some restorations carried out by the Umayyad caliph al-Walīd I in 706. Excavations at Wāsiṭ in Iraq have confirmed this date for the introduction of the first concave miḥrāb where there are two superimposed mosques; the lower one datable to the seventh century has no miḥrāb whilst the upper mosque has a concave miḥrāb. That was the dictionary definition by Petersen. Petersen also notes the history of the miḥrāb in his entry on Wāsiṭ: Wāsiṭ lies south-east of the modern town of Kut in southern Iraq. It was founded in 701 CE by al- Ḥajjāj, governor of Iraq, as a garrison town to replace Kufa and Basra which had been demilitarized after a revolt against the Umayyads. In 874 (note that this is 170 years later) another Friday mosque was built by the Turkish general Musa ibn Bugha in the eastern part of the city. The devastation wrought by the Mongols in the thirteenth century and by Timur in the fourteenth hastened the decline of a city that was no longer on the main trade routes due to a change in the course of the Tigris. The first mosque on the site was built by al-Ḥajjāj in 703; measuring 100 m per side, it was located next to the governor’s residence. Iraqi excavations revealed two superimposed mosques, the earlier of which had no miḥrāb. This confirms the early date of the mosque, as the first concave miḥrāb was introduced by al-Walīd in 707–9 in the mosque of Medina. We know about this reconstruction in Medina from al-Ṭabarī Vol 23, pg 141 when the Mosque of the Prophet in Medina underwent a major rebuilt. Al-Ṭabarī notes that the foundations were re-laid and the qibla wall was changed. Many of the early mosques underwent regular rebuilding, as they were expanded to accommodate larger and larger numbers of people. This was normal, and al-Ṭabarī doesn’t note many of these. But in Medina he adds the important bit of information that makes this noteworthy. The Qibla Wall was changed. From my survey of over 150 of the earliest Qiblas around the Muslim world, the change in mosque construction observed by Petersen, can be clearly seen. Moreover, it seems the change in the Medina Qibla wall mentioned by al-Ṭabarī was part of a significant shift happening on a wider scale. Soon after this, new mosques started facing Mecca in Saudi Arabia, and these were constructed with miḥrābs. But mosques still facing Petra generally did not have a miḥrāb niche. Sometime after the Mosque of the Prophet’s Qibla wall was changed a mosque to the north west of the Prophet’s mosque was rebuilt, and became known as the Qiblatain mosque, as that mosque maintained its old Qibla facing north, as well as having a new qibla facing south. In my database there are numerous mosques which demonstrate the Qibla changed from Petra to Mecca. It is my hope that scholars will pick up on change, and address it more thoroughly sometime in the future. Now it is interesting to note, that in some of the surviving mosques with two Qiblas, that one Qibla is often given preference over the other.

Interior of the Ibra Qiblatain mosque in Oman.

For example, in the Ibra Qiblatain mosque in Oman, seen here, the miḥrāb towards Mecca is notably larger, and the old Qibla towards Petra is much smaller. And even after the mosque was rebuilt, they maintained the two Qiblas in this mosque.

\ In his Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Petersen highlights the importance of the two mosques in Wāsiṭ. The first mosque in Wāsiṭ was constructed by al- Ḥajjāj. It was later torn down and a larger mosque was built right on top of the old mosque. Archaeological investigations started there in 1936 and excavations took place from 1939 to 1945 by Fuad Safar who later became the Iraqi Directorate General of Antiquities and Heritage.

Fuad Safr

The large Ḥajjāj mosque and a building known as the minaret was cleared out, including a tomb and a school that date back to the seventh century. Preservation took place on some parts of the minaret due to walls been worn out, but no real maintenance was carried out. So the place is still very much in ruins.

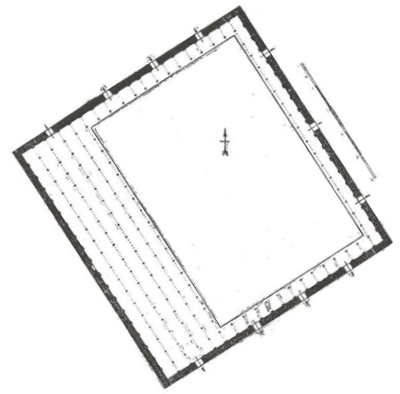

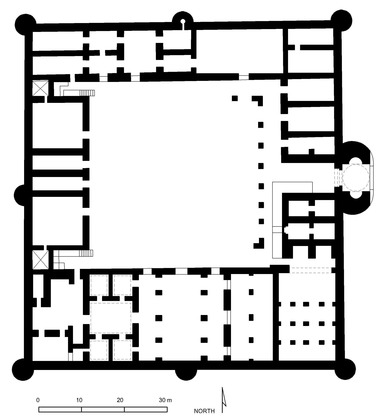

The Hajjaj mosque at Wasit

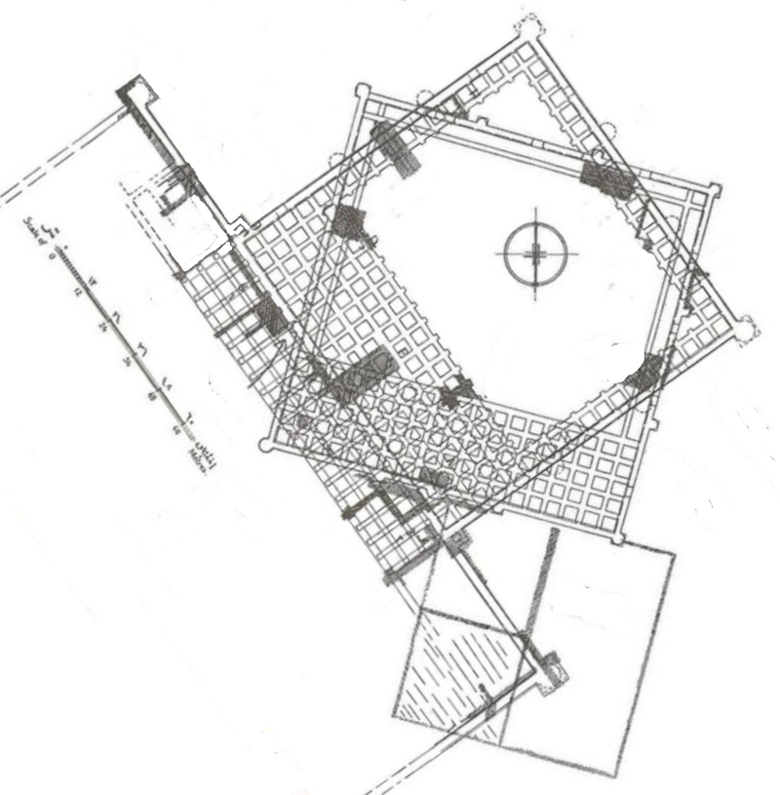

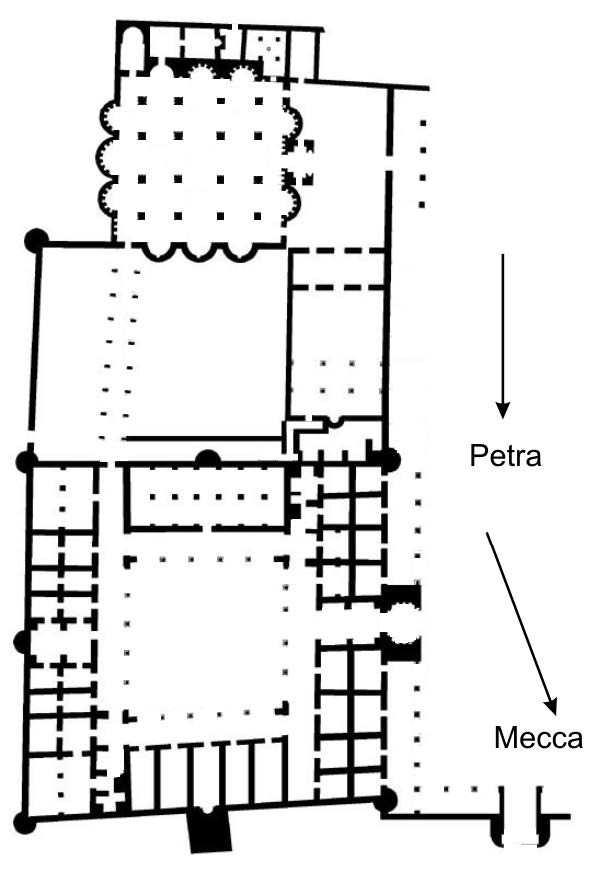

Above is a drawing made by the Safar expedition. This is the older Hajjaj mosque that was underneath the later mosque. The drawing below was made by Creswell showing the two mosques and their orientations to each other.

The two Wasit mosques

There are several things to note from these drawing. First, as Creswell’s drawing shows, there are two mosques, one above the other. The earliest mosque was built by al- Ḥajjāj and faced a Between position, as did all of the mosques that Ḥajjāj commissioned during his lifetime.

The later mosque was built on the same location but with a different orientation. As can be seen from the Wāsiṭ mosques, and also the two superimposed mosques in Tiberius, the original building was torn down, and the rubble was spread over the old foundation.

Tiberias Mosque

Tiberias Mosque foundation shows an earlier mosque under the large Umayyad mosque.

Then the new mosque was built above the old one. In this way the original foundation was preserved so today archaeologists can determine the foundation of both of mosques.

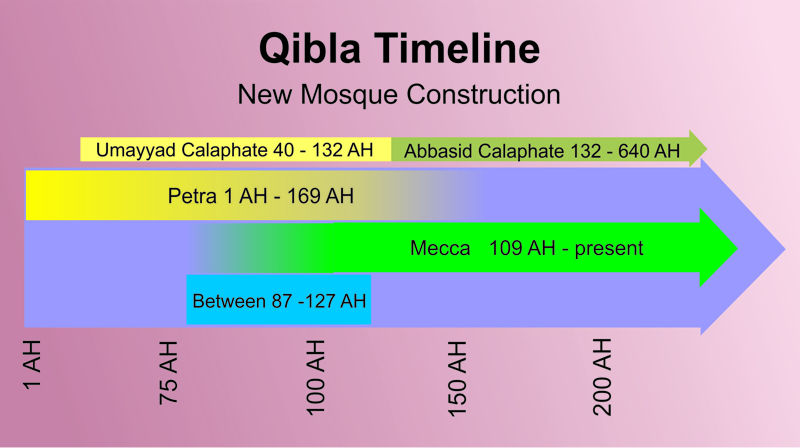

To fully understand how the miḥrāb developed I find it helpful to look at a timeline. The timeline below illustrates the Qiblas used in new mosque construction from the start of the Islamic era until around 250 AH. We will not look at everything in detail as most of these subjects have been covered in other videos.

Mihrab Time Line

During the reign of the ’Uthmān ibn Affan (23-36 AH), the caliph ordered a sign to be posted on the wall of the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina so that the faithful could now identify the direction in which to address their prayers. Up until this time historians could not explain this development, since they assumed there was no question as to which direction the faithful should pray. The entire building always faced the qibla. But now, however, a sign was provided seeming to indicate that there was some question about the qibla and maybe a new optional qibla had been introduced.

- In this year al-Walīd b. ‘Abd al-Malik ordered the pulling down of the mosque of the Messenger of God, may God bless and preserve him, and the pulling down of the rooms of the wives of the Messenger of God, may God bless and preserve him, and the incorporation of them into the mosque. Muḥammad b. ‘Umar mentioned that Muḥammad b. Ja’far b. Wardan al-Banns ‘said: I saw the messenger sent by al-Walīd b. ‘Abd al-Malik. He ar¬rived in the month of Rabi’ I in the year 88 (February-March 707 CE) with a turban wound round his head. He entered into the presence of ‘Umar b. ‘Abd al-’Azīz bearing al-Walīd’s letter ordering him to incorporate the rooms of the wives of the Messenger of God, may God bless and preserve him, into the mosque, and to buy (the land) behind it and beside it so that it might [measure] two hundred cubits by two hundred cubits. He also said to him (in the letter): “Change (move) the Qibla if you are able, and you are able, because of the standing of your maternal uncles …”* Ṭabarī Vol. 23, Year 88, page 141

So during the reign of Al-Walīd ibn ’Abd al-Mālik (Al-Walīd I, 86-96), the Mosque of the Prophet (the Masjid al Nabawi) was completely renovated and the governor of Medina, ’Umar Ibn ’Abdul Azīz, ordered that a niche be made into one wall to designate the qibla. ’Uthmān’s sign was then placed inside this niche. Eventually, the niche came to be universally understood as identifying the qibla direction, and so came to be adopted as a feature in other mosques. A sign was no longer necessary.

Mihrab Time Line

I do not think it was a coincidence that the data shows that very soon after al-Ḥajjāj changed mosque orientation the miḥrāb niche started being used, most likely to lessen confusion in some mosques. We can see from the mosques we have examined, that the miḥrāb did not become universal until the Abbasid era, and by then it was associated with a Mecca Qibla. It seems there may have been confusion in some mosques over which way to pray, so new mosque construction adopted the miḥrāb so that the faithful could pray with confidence towards Mecca in Saudi Arabia.

But where did the idea of a miḥrāb come from? I would like to suggest that it came earlier.

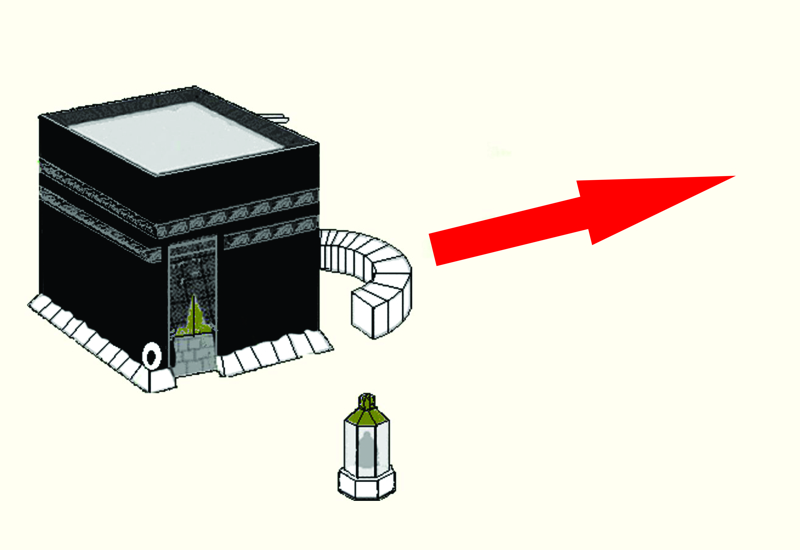

The Ka'ba in Petra

Here is a satellite photo of the first Ka’ba was in Petra. Around it was a walled courtyard with the temple of Dhu-Shara/Hubal on the south side. In the west wall of the courtyard there was a niche where the wall curved around the grave stones of Ishmael and Hagar. I would like to propose that the first miḥrāb was based on the hatim wall of the Petra Ka’ba. That niche was an integral part of the Ka’ba complex, so when a new Ka’ba was built in Mecca, in Saudi Arabia, people also wanted a curved hatim wall. We learn from Al-Ṭabarī Vol 20:176 that Ibn Zubayer, in 65 AH had the hatim wall attached to the Ka’ba.

‘Abdallih ibin al-Zubayr rebuilt al-Bayt al-Ḥarām incorporating the Ḥijr within it. Al-Ṭabarī Vol 20:176

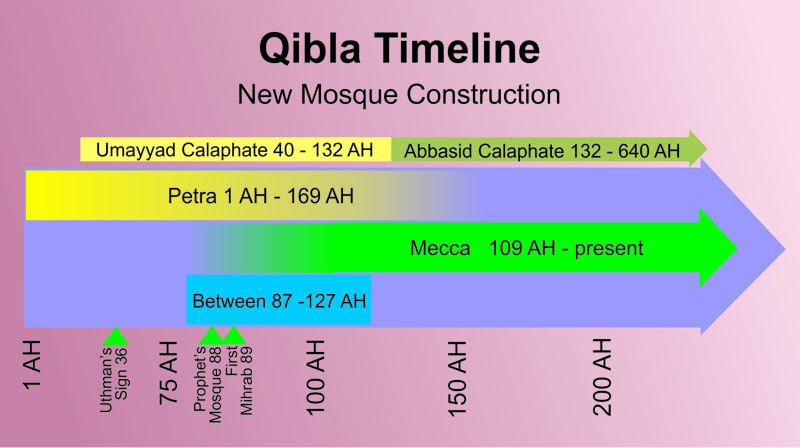

And this is what we see in Mecca today. The hatim wall in Mecca was placed so that is it closer to the Ka’ba and attached to it. I believe this gives the Ka’ba direction, so that it is facing the first, original Ka’ba.

The Ka'ba in Mecca faces the Ka'ba in Petra

In a way, the hatim wall in Mecca is acting as a miḥrāb, because it faces towards the original Ka’ba in Petra. This illustration shows the orientation of the Ka’ba and the hatim wall in Mecca

The Ka'ba in Mecca faces the Ka'ba in Petra

It seems that a new function was now attached to the hatim wall, now orienting people towards the original Ka’ba. So what better way to illustrate the direction of prayer, than to use a niche in the Qibla wall?

The Ka'ba in Mecca faces the Ka'ba in Petra

According to the Huma al-Numur inscription in Saudi Arabia, the Ka’ba there was constructed in 65 AH. Al Tabari (Vol 20 pg 123) tells us that Ibn Zubayr demolished the Ka’ba and placed the Black Stone on silk in a temporary wooden stand. It is also the year that ’Abdallah ibn Zubayr also claims he finds the foundation stones that Abraham laid for the first Ka’ba, but no location is mentioned for this new Ka’ba. However we can date the Ka’ba in Saudi Arabia through the Huma al-Numur inscription and specifically through the attaching of the Hatim or curved wall to the north side of the Meccan Ka’ba. This small curved all ‘faced’ the Hijr of Ishmael, or the Rock of Ishmael, that marked the burial place of Ishmael and his mother Hagar in far off Petra.

I would like to propose that this curved wall was the basis of the very first miḥrāb ever constructed. After this, a curved wall in the form of a niche was incorporated into new mosque construction.

Khirbet al-Mufjar near Jericho

Some builders decided to add a miḥrāb to some existing buildings, such the Qasr at Khirbat al Mafjar near Jericho. In this case the wall to an inner room was opened up and a new reinforced wall was added facing the Between Qibla. A later Qibla is also evident at the Dome of the Chain in Jerusalem. This structure is beside the Dome of the Rock, but much smaller. From the use of different construction material it seems that the qibla on this structure was a later addition, indicating to the faithful the direction of prayer towards Petra.

Dome of the Chain, beside the Dome of the Rock

Now, the last thing we want to address, is how to identifying places of prayer before the miḥrāb invention. In most mosques, one has only to look for the Qibla wall. This is the wide flat wall across the front of the mosque.

If the mosque is square, then all four sides might be considered. However, usually the rows of pillars identify the front and back walls, as Muslims liked to line up in long wide lines, where everyone’s shoulder is close to shoulder of the person beside them.

Standing shoulder to shoulder along the pillars

Because of the positioning of pillars, this is usually only possible in two directions, facing front or back. The front is usually obvious, since the door to the mosque is most often at the back. So even without a miḥrāb, it should immediately be obvious which way the faithful faced in the mosque. From Qasr al Humayma, the long wide room at the north end of the Qasr appears to be the prayer room. Notice it has access directly to the central courtyard so that the faithful did not have to pass through residential quarters to reach the Qasr Mosque.

The prayer room at Humeima is on the north wall.

In Khirbat al Minya near Jericho the prayer room is at the southern side of the Qasr, and again opens directly onto the courtyard. It may have been the room in the center or most likely in the right corner. The centre room may have been a reception room for the caliph. No miḥrāb is present in either of these Umayyad structures.

Khirbat al Minya

In closing, let me address something Petersen said in his definition of the miḥrāb. He stated: In the cave beneath the rock in the Dome of the Rock there is a marble plaque with a blind niche carved into it which, if contemporary with the rest of the structure, may be dated to 692 making it the oldest surviving miḥrāb. That idea of the oldest surviving miḥrāb has been challenged by Eva Baer in her article: The Miḥrāb in the cave of the Dome of the Rock. She arrived at the following conclusion: “The characteristic details of the miḥrāb in the Cave of the Dome of the Rock suggest two conclusions. First, the date cannot be earlier than the second half of the ninth century… Second, it is possible that the actual sponsor of the miḥrāb was a member of the Ikhshidid or Fatimid dynasty. (323 - 358 AH). This dates the miḥrāb much later, so it is not a candidate for the oldest surviving miḥrāb. In this video I have tried to demonstrate that the miḥrāb was a later invention, that came into play when al- Ḥajjāj began building his mosques using a Between qibla. A few years later it was adopted by the Abbasids, and used in mosques ever since to indicate the direction of prayer towards Mecca in Saudi Arabia. But the very earliest mosques did not have a miḥrāb, they had a simple Qibla wall. Nothing else was needed, since originally all mosques in the first years of Islam faced Petra, in southern Jordan. It was only after other Qiblas were introduced that a sign, and later a miḥrāb was introduced.

I am Dan Gibson, and this has been another video in the series Archaeology and Islam.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baer, Eva. The Miḥrāb in the Cave of the Dome of the Rock. In Muqarnas III: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture, edited by Oleg Grabar. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1985. Creswell, KAC, Fortification in Islam before A.D. 1250, Aspecta of Art Lecture, Henriette Hertz Trust, From the proceedings of the British Academy, Vol 38, London, 1952

Creswell, KAC, A Short Account of Early Muslim Architecture,

Fehervari, G., *Development of the Miḥrāb down to the XIVth Centu*ry, London, Ph.D. 1961

Longhurst, Christopher Evan, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, Morocco, Miḥrāb: Symbol of Unity and Masterpiece of Islamic Art and Architecture

Peterson, Andrew, Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, 1999

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!