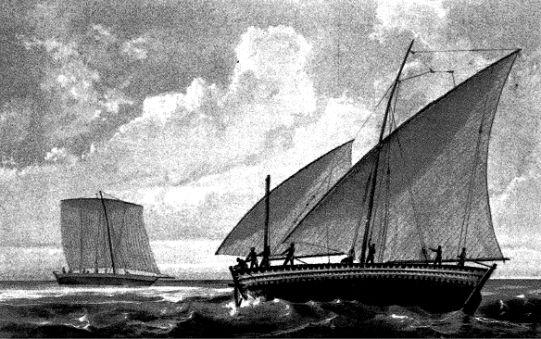

Do ancient petrogyph drawings along the south coast of the Arabian Peninsula, provide us with clues that help us understand the history of the development of the dhow? In this article the author compares these ancient drawings with dhows that have been documented in the 18th and 19th centuries demonstrating that the history of the dhow goes back many centuries.

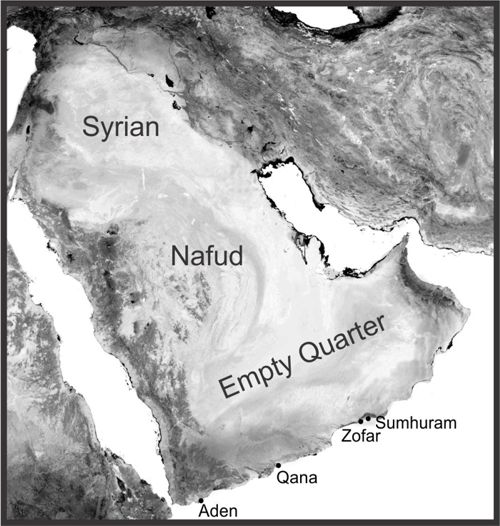

The southern coast of Arabia has long been an isolated undeveloped area, home to warring mountain tribesmen and inhospitable deserts. In ancient times shipping along this coast was serviced by a few small ports which provided fresh water and supplies for passing ships, as well as emporiums for the many kinds of incense grown farther inland.

undefined

All along the coast, locals eked out a sparse living, based on fishing, dates, and the yearly incense harvest. No major cities existed along this coast with the exception of the ports. Aden in the south was a major port, followed by Qana (Mukalla) to the east. Two smaller ports follow as one moves northeast along the coast: Al Balid, also known as ancient Zofar (modern Salalah), and ancient Sumhuram (modern Khor Rori). Between these four ports spread miles and miles of coast where the low mountains of Arabia and the blowing desert sands of the Empty Quarter meet the ocean.

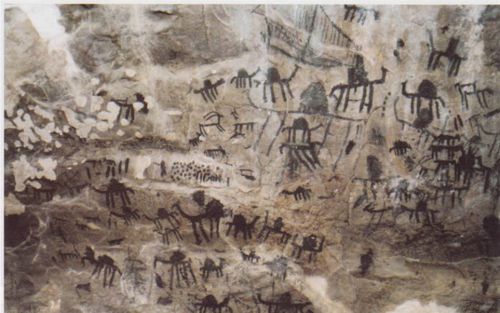

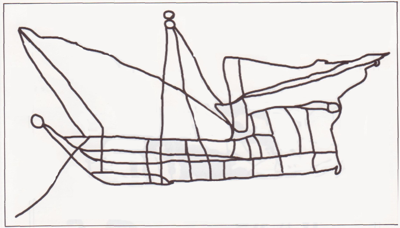

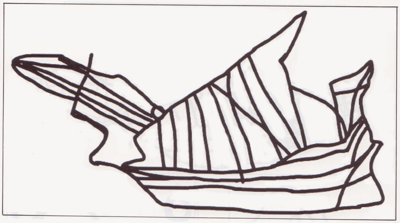

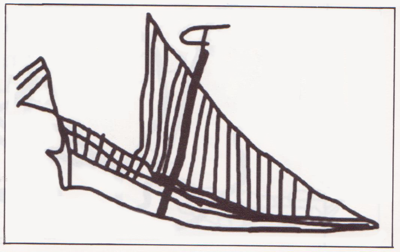

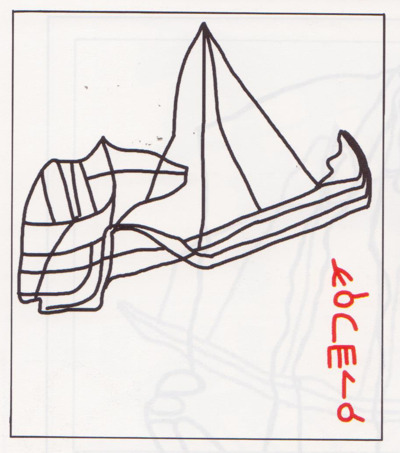

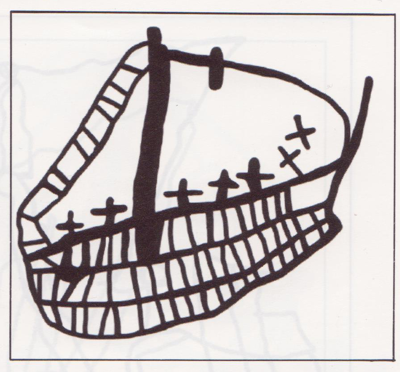

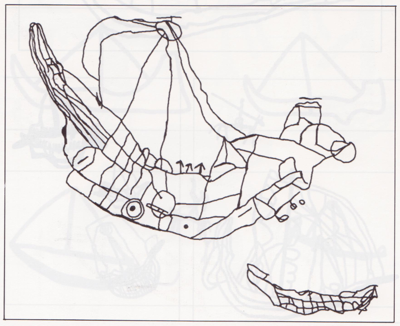

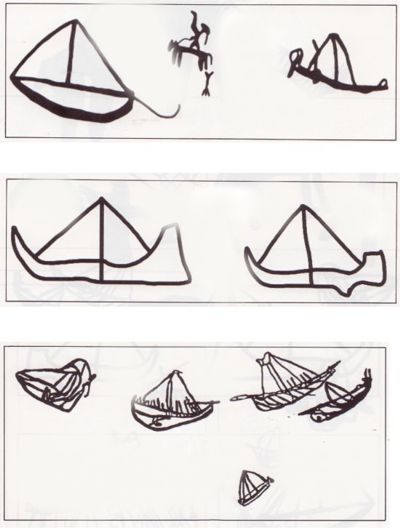

The petroglyphs examined in this article can be found along the coast between Qana and Zofar. Long ago people etched simple drawings in the rock that recorded events and observations that were memorable to them. These drawings or petroglyphs leave us with a few brief glimpses into the past. Among the events recorded are memorable hunts, invasions, and of course the passing of various kinds of ships along the shore. The ancient observers were not artists or draftsmen, but local people who scratched or etched what caught their fancy. Their drawings were neither technical nor detailed. However, when one studies these drawings a few interesting observations can be drawn.

Camels and depictions of desert life are in abundance.

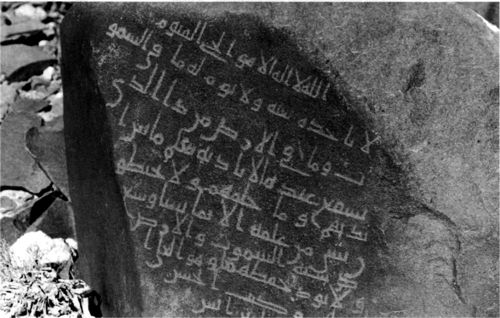

There is one early Arabic inscription, in this case a Qur’anic quote. The script comes from an early time when the Arabs did not use vowels or dots. dots.

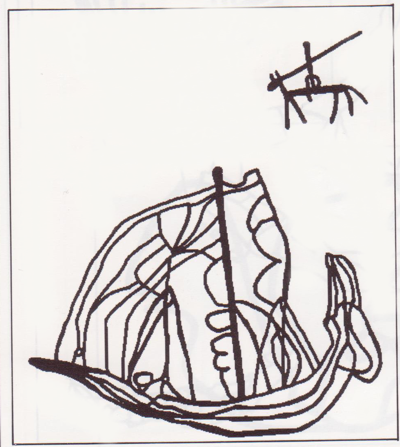

Notice ships and desert scenes mixed together.

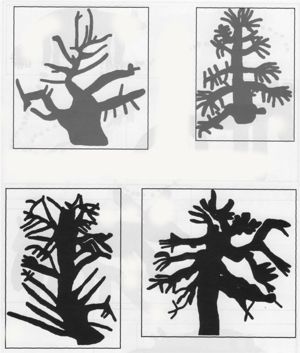

The frankincense trees and the yearly harvest were an important topic.

undefined

Observations

- While it was impossible to date the petroglyphs, the presence of early Arabian scripts demonstrate than many were made in pre-Islamic times. The only Arabic script comes from a time before the Arabic language used dots, even on consonants. This would put the probable date of the petroglyphs before 700 AD. However, there is the possibility that some of the etchings were made in more modern time.

- There are more than 20 ships among the petroglyphs. The absence of ships that use oars stand out. Many historians have imagined that ships powered with oars were used for trade on the Indian Ocean much like they were used on the Mediterranean. Almost all of the petroglyph ships are some type of dhows.

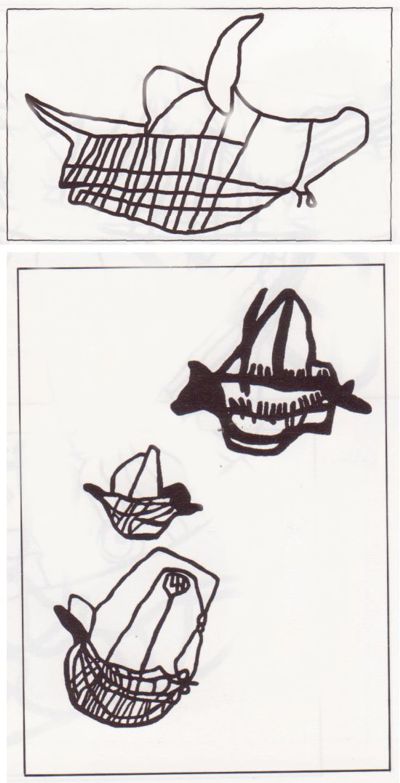

- There are a surprising variety in the types of dhows depicted. Perhaps the artists only drew new types of ships as they saw them. Many of the petroglyphs emphasize something unusual which the observer noticed and then emphasized in his drawing. To the causal observer this may make the petroglyph appear strange. Things normally drawn may be under-drawn or missing, and one part of the ship is over-drawn. When one realized that the artist is trying to communicate that he saw a new type of ship, the petroglyphs become more meaningful.

- There were far too many petroglyphs to catalogue all of them. Since our interest was on ancient maritime trade, these are the main ones recorded.

- There are many more petroglyph drawings along the Arabian coast which have not yet been catalogued or published in any way. As the coast is very long and isolated, finding these petroglyphs would be a challenge. Many are found in the mountains, somewhat removed from the shore, and many are found in caves presumably where the artists lived.

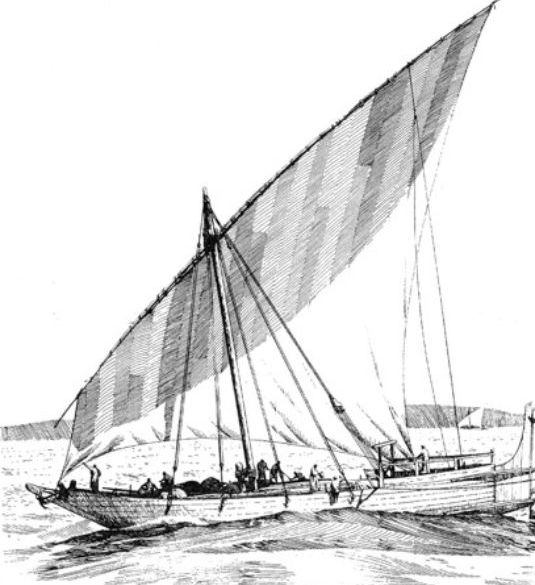

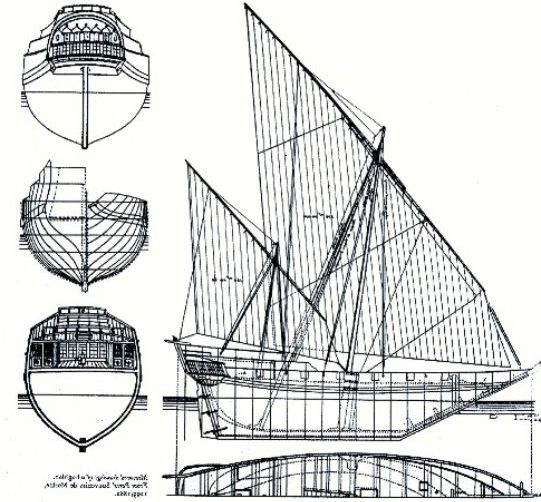

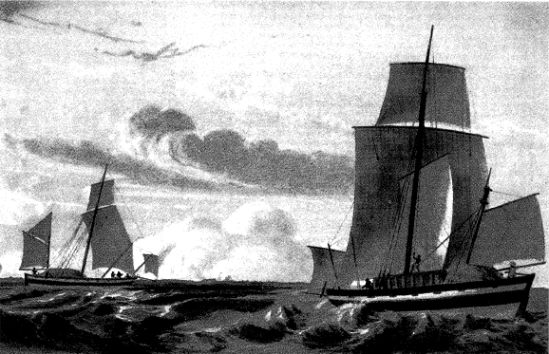

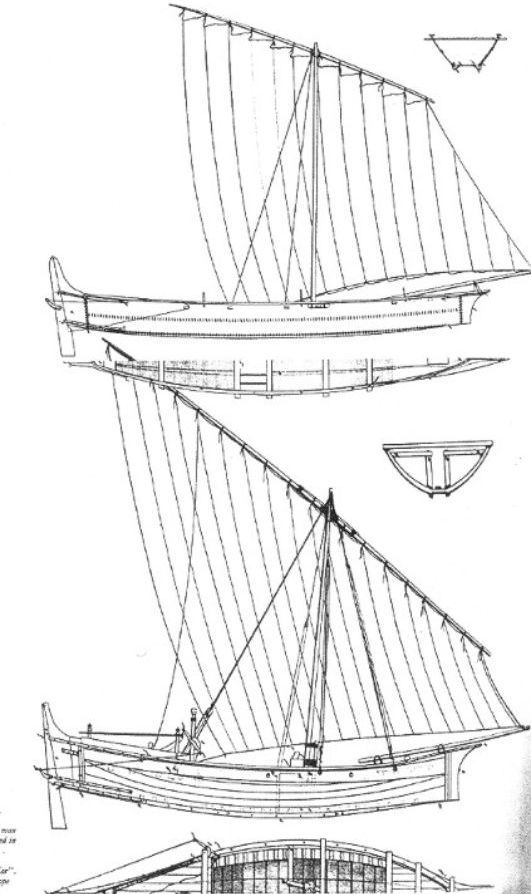

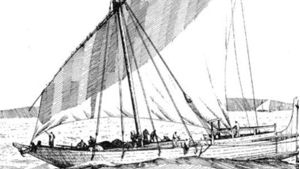

- In this study I have used the extensive nautical observations and drawings of Francois-Edmond Paris who was born in Paris on 2 March 1806. His travels took him around the globe several times, and all along the way he recorded and sketched the various ships they encountered. His work is preserved in two volumes of Essai Sur La Construction Navale des Peuples Extra-Europeens and also his book Souvenirs de Marine published by Musce’de Marine, Paris 1882.

- It is hoped that this short paper will inspire others to examine petroglyphs of dhows more closely, so that a better timeline for the development of the dhow may be constructed.

| Petroglyph | Notes | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

|

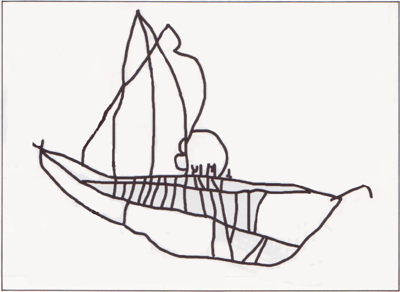

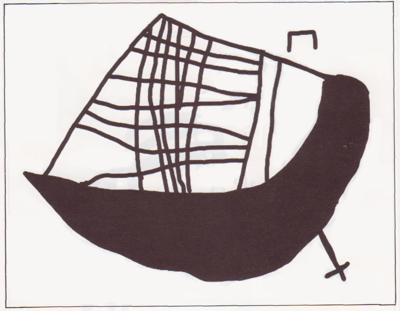

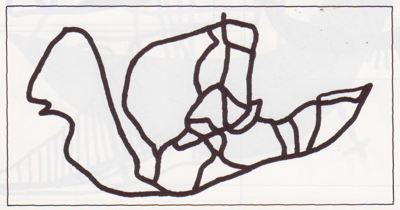

Very early dhows used a large mainsail, and an oar for steering. The artist here observed the mast, rigging and cross member. The bow and materials stacked on the deck were memorable to the artist as he left the shore to make his drawing on the rocks. |  |

|

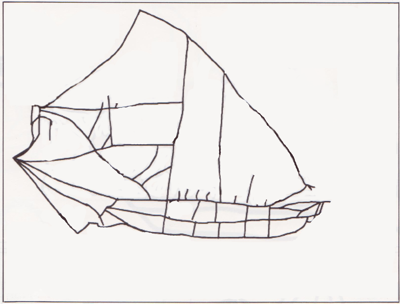

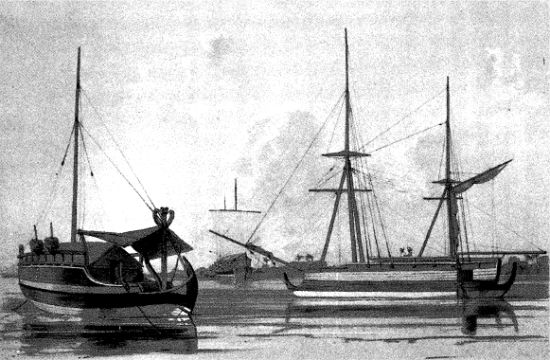

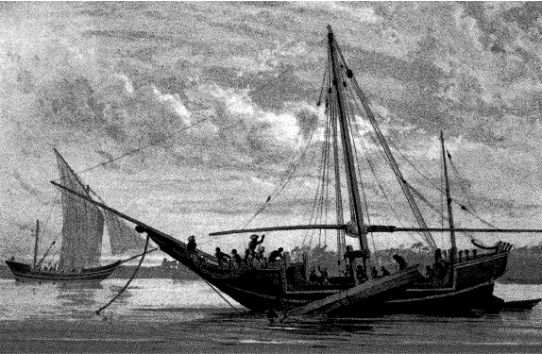

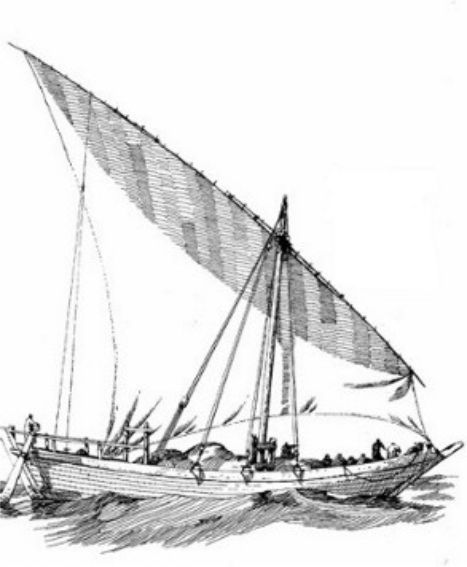

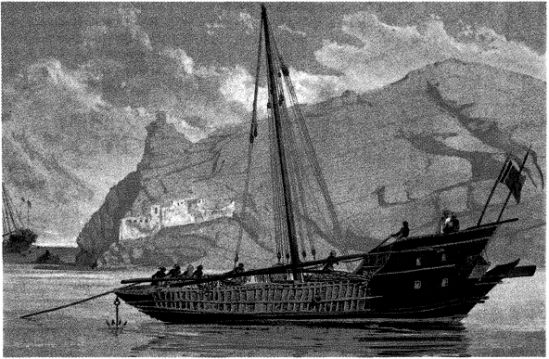

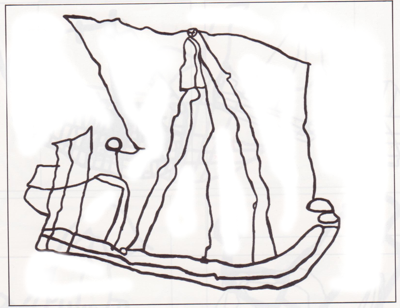

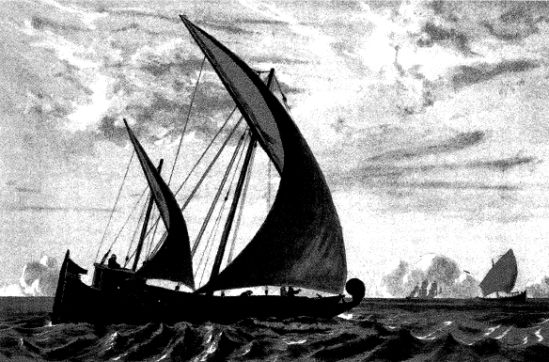

The Arab Baggala is similar to the Indian dhow with their two masts and distinctive yards and sails. The yard is almost always as long as the boat. They carried horses, dates, tasar, rice, timbers and spices. Usually one trip per year was made from the Red Sea to India or beyond. |  |

|

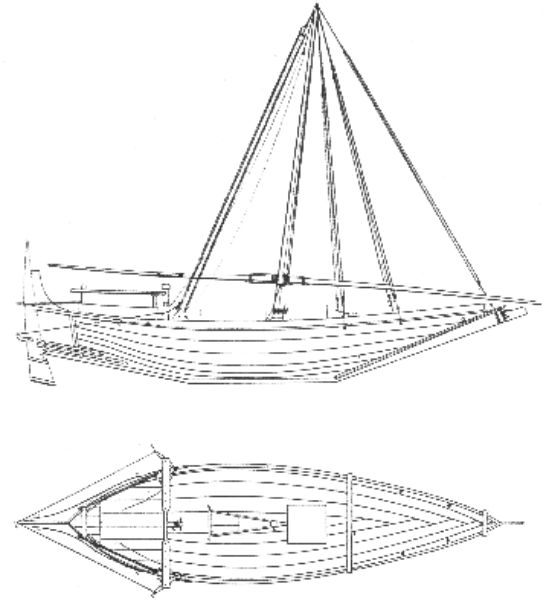

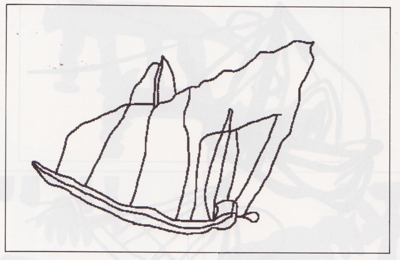

This ship was hard to identify. It appears to be a Malay ship about 15 metres long, with two tripod masts, with a tall, square sail with reef-bands in front, and a distinctive spanker sail behind. However, it could be a coaster (see below) |  |

|

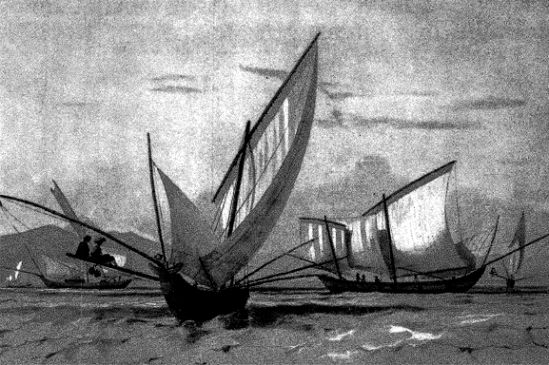

These coasters were similar to the Baggala, but had a very distinctive bow sprit. The rear was raised on an extended vault and the front often had a lower deck. These coasters were solidly built and often used to carry heavy loads, especially timbers. They were often used on the Malabar coast for transporting teak. |  |

|

The rigging on a Bengali Patile is very distinctive. These boats were very strong and heavy with a flat, vertical rear, a very slanting front, flattened out at the bottom, The rudder was positioned at the side, is triangular. |  |

|

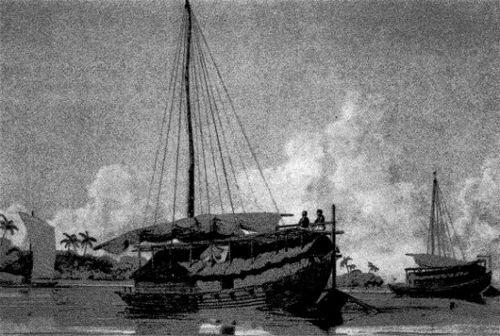

The baggarah used a rope steering gear. The hull of this small boat was very similar to a battil, but the stern-piece continued in a straight line instead of the club like shape of the battil, but lacked protection despite it’s high stern post. This vessel was also known as a shahuf, and was used as a fishing vessel along the coasts of the Oman and Yemen. |  |

|

While it is difficult to be certain of the identity of this boat, it does appear to be an early dhow, with stern rudders, and a rope system of steering. Once again the high main yard is the distinctive element. |  |

|

The artist was struck with several important elements in this petroglyph. The square central sail, and the forward and rear desk make it appear to be a Pansway, generally identified as an Indian coaster. |  |

|

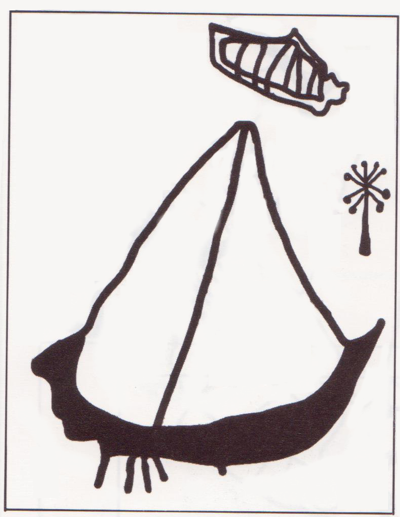

Dungiyahs had a single mast and a high rear. Their yard was not as long as the baggala. They are believed to be the most ancient type of vessel sailing the Indian Ocean, and it is thought that they even go back as far as the expedition of

Alexander. They were often poorly constructed. |

|

|

The Beden Safars are found only at Muscat in Oman, and were used for tuna fishing. Their strong central mast and heavy lines forward and aft can be clearly seen in the petroglyph. Their round bottoms and shallow draft made them easy to beach. |  |

|

These coasters are very short, with large flat bottoms. They seem high as their decks are often stacked with bales. At the front, instead of a bow sprit there is a long narrow platform surrounded by brightly colored railing. Three masts often resemble lug sails. They were reportedly ungainly and cumbersome. |  |

|

Many of the drawings are impossible to identify, outside of the lateen sail that was typical of the dhow. The earliest dhows used either a single or dual oars on the sides of the ship for steering. The lateen sail is distinctive as it hangs from a triangular yard and main sail. |  |

|

The artist here observed a ship with two masts, the larger in the center with a square yard arm, and a smaller mast at the rear. This appears to be a Donis, most frequently-used as coasters along India and Ceylon These stitched ships often appeared to be poorly constructed, but it is claimed that they lasted for a century. |  |

|

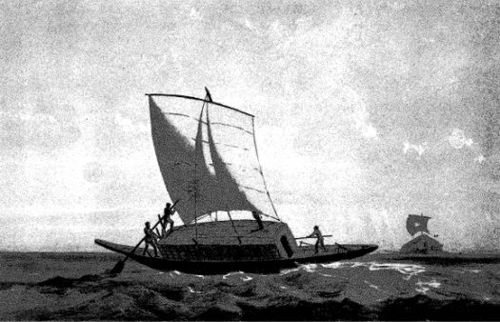

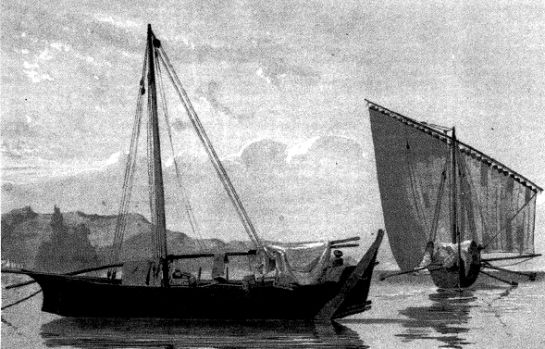

Garookuhs had two lateen sails. The rear of the boat was high and curved with a narrow cabin, open at both ends. It always had two small side-windows through which the rudder-levers passed. These boats carried a lot of sail and were very sea-worthy. They only carried light cargo and were more suitable for fishing than for trade. |  |

|

Is it possible that the artist observed a Gay-You fishing boat? These were popular on the Bay of Tourane in Vietnam. There were two main sails with a rectangular one at the rear used only for tacking. The yard extend higher than the mast making them quite distinctive. |  |

| Another, perhaps more likely option, would be a Pondicherry Indian coaster (pictured right). They had a large lateen rear sail and a smaller one to the front. They had no reefs, and their yards were not so vertical as the Mediterranean ones. The main mast rose noticeably higher than the yard arm. While the rigging is different than a Gay-You the exterior ends of the deck beams along the hull may be what is illustrated by the extra line along the hull in the petroglyph. |  |

|

|

Badans were popular boats, the smaller ones used for fishing (Badan-seyad) and the larger ones used for cargo. (Badan-safar). These ships were sewn and had a double keel and a rope system for steering. Most Badans were smaller is size and did not venture into deep water far from the coast. If their sails were down they would appear as a small boat with the mast and lines forward and back. |

|

|

Other petroglyphs were harder to identify. Clearly the ancient artists were not sailors and did not understand the importance of some parts of the ships they were drawing. However, the fact that they were recorded long ago is significant in themselves. |

|

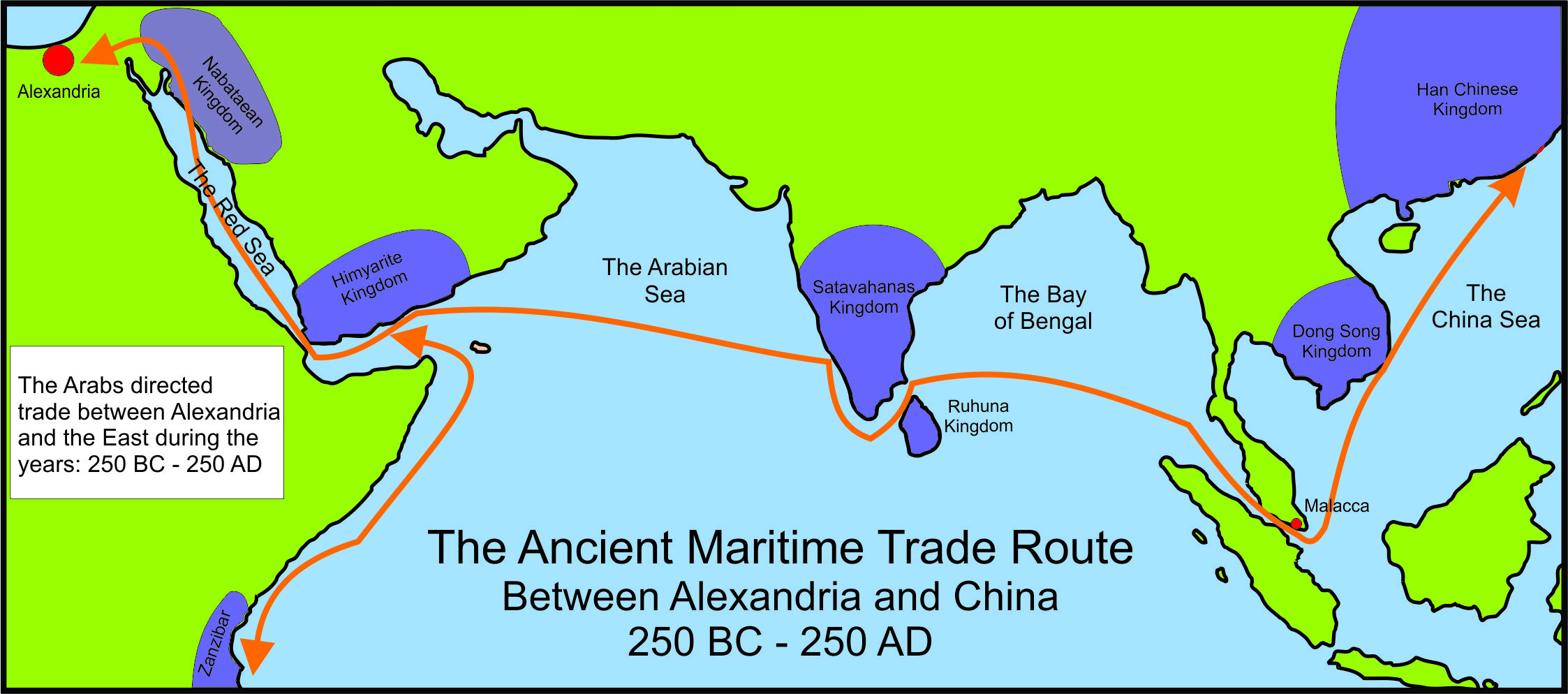

What we can learn from these few simple petroglyphs? First, it is obvious that the dhow has long been used for transporting goods along the Arabian coast-lands. One early mention of boats used for the incense trade comes from 24 BC when Nabataean boats were actively collecting incense from an island off the coast of Yemen and delivering it to northern Red Sea ports. According to Agatharchides (130 BC), the Sabaeans of southern Arabia (Yemen) also made use of rafts and leather boats to transport goods from Ethiopia to Arabia. (Photius, Bibliotheque VII) Agatharchides also tells us that the Minaeans, Gerrheans and others would unload their cargoes at an island off the coast so that Nabataean boats could collect it. In other words, he suggests that although the Sabaeans themselves may have confined their maritime activities to crossing the Red Sea, the Nabataeans in the north had already taken to maritime transport by the second century BC. (Agatharchides 87, and cited by Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca III 42:5 and by Artemidorus in Strabo Geography xvi, 4:18, as well as Patricia Crone in her book Meccan trade and the rise of Islam, (Crone, 2004, page 23) The island in question was probably Tiran. (Woelk, Agatharchedes page 212)

Second, the wide variety of ships observed and sketched demonstrate that over the years dhows from many different locations traveled along the coasts of Arabia including Arab dhows as well as Indian coasters. The use of these boats remained relatively unchanged until modern times. Fortunately Francois-Edmond Paris recorded drawings of these dhows before they disappeared.

As we mentioned, Francois-Edmond Paris was born in Paris on 2 March 1806. In 1820 he entered the Naval Academy at Angouleme, and graduated with honors in 1824. Assigned as ensign to the ship Astrolabe in 1826, he made his first voyage of circumnavigation, under the command of Dumont d’Urville. During this journey, his remarkable talents as a hydrographer and a draughtsman emerged. After his return to France in 1829, he subsequently served in West Africa and Brazil. His second voyage of circumnavigation was made on the corvette Favorite under Laplace (1831-33), during which he was made Lieutenant. From 1834 to 1836, he commanded the sloop Castor in Algeria, and 1837 saw him undertake his third journey round the world on the Artemise, once more commanded by Laplace. It was during this voyage that he visited a foundry in Madras, and fell into the workings of a steam engine while trying to examine its mechanism; his left forearm had to be amputated. In 1841 his scientific observations and studies of non-European vessels were officially recognized by the French Admiralty, who encouraged him to publish them, in a volume entitled Essai Sur La Construction Navale des Peuples Extra-Europeens.

After long campaigns in the Indian ocean, and South China seas, his valour was rewarded with a promotion to Captain. Paris also took part in the Crimean campaign, including the siege of Sebastopol. He was elected a member of the Academy of Sciences in June 1863, and made Vice-Admiral in August 1864. He retired from active service in March 1871, and was nominated curator of the Naval Museum at the Louvre. He died in Paris on 8 April 1893.

It is in his Essai Sur La Construction Navale Des Peuples Extra-Europeens that Francois Paris has put together the fruits of his observations of naval architecture gleaned during three voyages round the world. In his preface to the work, he claims that these drawings and plans were never intended to be published, and were executed in order to fill the gaps left in this field by his predecessors. The value of his work was illustrations for the official account of the voyage of the frigate Artemise. Some 800 drawings on almost 300 plates were published in 1841, under the aegis of the First Lord of the French Admiralty. The original edition was issued in a very limited edition, and, according to experts, less than a dozen copies are extant, mainly in maritime libraries and museums. In his preface, Paris states that it should not be read from beginning to end, but used as a work of reference.

Today we have a rich resource in Francois’s work at cataloging the ships he observed. Not long after his work, dhows and Indian coasters began to dwindle. These ships, so admired by Marco Polo, Ibn Majid, and others became a thing of the past. By 1940 only 166 dhows were recorded arriving at Mombasa, and by the 1960 this had dropped to 43 and to 23 in 1976. Today it is rare to see a dhow along the coasts of Arabia. Modern ships of steel and fiberglass have replaced the old sewn wooden boats

Bibliography:

Crone, Patricia, Meccan trade and the rise of Islam, Princeton University Press, 1987

Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1993

Oman, a seafaring nation, 2nd edition, Ministry of National Heritage and Culture, Sultanate of Oman, 1991

Paris, Francois-Edmond., Essai sur la Construction Navale des Peuples Extra-Europeens. Vol/ 1 and 2, Paris 1845

Paris, Francois-Edmond, Souvenirs de Marine, Musee de Marine, Paris 1882

Photius, Bibliotheque VII, Collection Des Universites De France Serie Grecque, Les Belles Lettres, 2003

Strabo Geography, Ulan Press, 2012

©Dan Gibson, 2013

Page Discussion

Membership is required to comment. Membership is free of charge and available to everyone over the age of 16. Just click SignUp, or make a comment below. You will need a user name and a password. The system will automatically send a code to your email address. It should arrive in a few minutes. Enter the code, and you are finished.

Members who post adverts or use inappropriate language or make disrespectful comments will have their membership removed and be barred from the site. By becoming a member you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy, Cookies & Ad Policies. Remember that we will never, under any circumstances, sell or give your email address or private information to anyone unless required by law. Please keep your comments on topic. Thanks!